Free Persons of Color and Their Freedom Papers

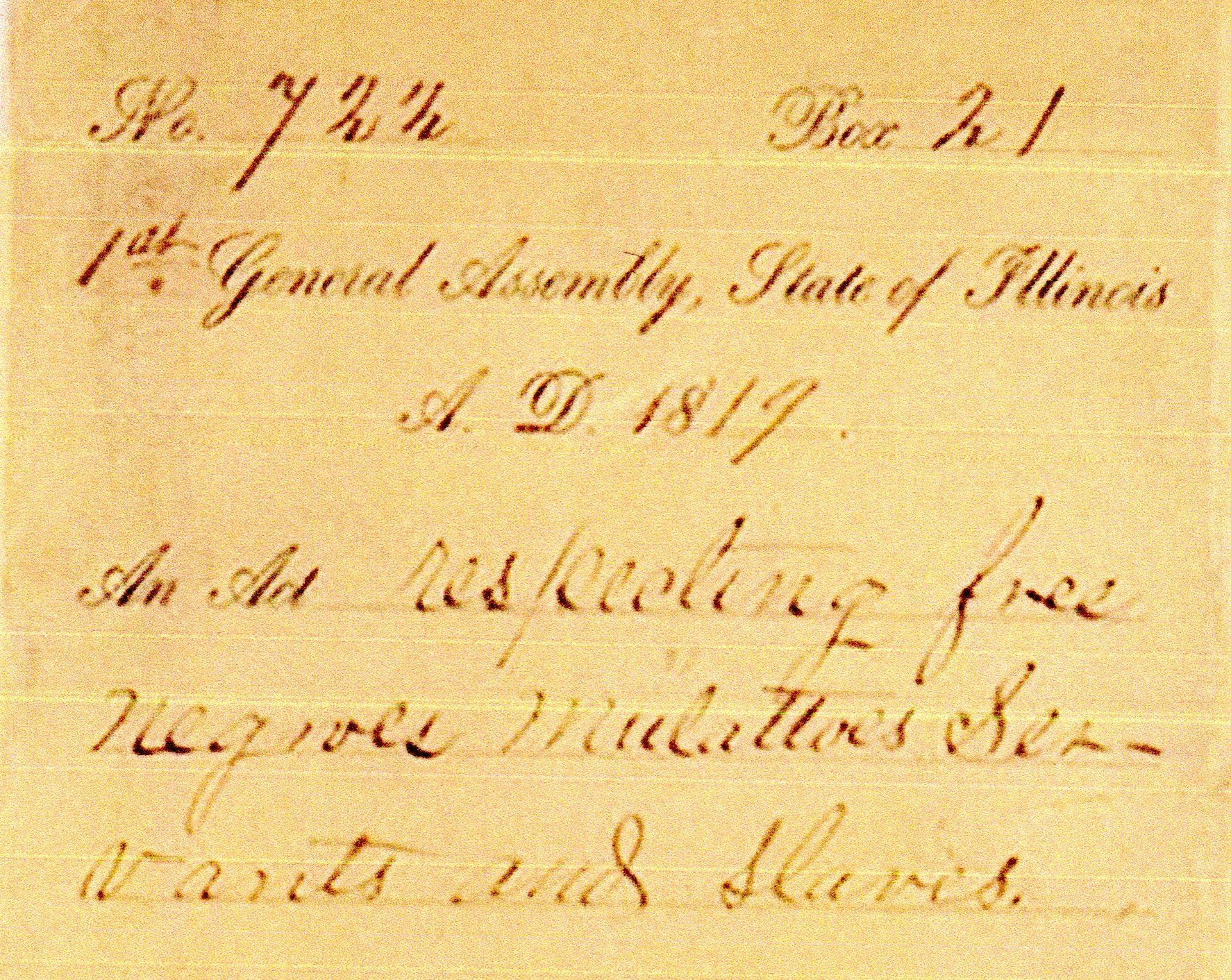

In 1819, less than a year after Illinois became a state, the first Illinois General Assembly passed: “An Act Respecting Free Negroes, Mulattos, Servants, and Slaves.” This act, in 25 Sections, outlined how free persons of color should be registered and treated, their rights and responsibilities, and the fines and punishments to be administered for violations of the Act.

Sec. 1 of the Act read in part, “no free black or mulatto person shall be permitted to settle or reside in this state unless he or she shall first produce a certificate signed by some judge or clerk of some court of the United States of his or her actual freedom,” and that “it shall be the duty of such clerk to make an entry thereof . . . after which it shall be lawful for such free negro or mulatto to reside in the state.”

In Adams County Illinois, a number of these proofs of freedom, entered by circuit court clerks Henry H. Snow and C. W. Woods, survive in “Book B” of the Circuit Court Clerk’s Office.

John Larkin Williams appeared before the clerk of the Adams County Circuit Count on April 25th, 1853, with proof of his free status in the form of a declaration offered by John Tillson, Sr. Tillson, a well-known citizen of Quincy, Illinois, was once one of the richest men in Illinois, having made a fortune speculating on land sales in the Bounty Lands between the Illinois and Mississippi rivers.

In his statement before clerk C.M. Wood, Tillson certified that he had known John Larkin Williams since said Williams was 11 or 12 years old, when he had been “bound out” to Tillson from the House of Industry in Boston Massachusetts. Since that time, he stated, Williams had lived with him in the state of Illinois, as a free person. The House of Industry, founded in Boston in 1822, was a facility housing “rogues, vagabonds, common beggars . . . ,” which functioned as a workhouse for the poor.

Tillson ended his statement by noting that Williams, who was by then around 36 years of age, “being now desirous of immigration to California or to some place South or West…” was then and had always been a “free coloured man.” By this action on April 28th, 1853, Tillson was providing Williams with concrete documentation of his freedom – his “Freedom Papers.” Less than two weeks after giving this testimony, John Tillson Sr. died suddenly while on a business trip to Peoria, Illinois.

On June 13th, 1836 Anthony Touzalin, a prominent merchant and farmer from Columbus, Illinois appeared before circuit clerk H.H. Snow to state that he had known William Foote from infancy and that “said William is free and born of free parents.” He stated further that he knew William’s parents to be “of the Island of Jamacca,” and that William had come to the United States with him, Touzalin, as a servant. That he had traveled to the state of Illinois in October 1835, and “has resided with him ever since, and that said William is a good jobber and trusted character.”

Foote’s parents, born slaves, had become free British subjects through an act of the British government, and their son had thus also become a free person. William Foote stayed in Quincy for the rest of his life, operating a barber shop on the west side of the Square, and living above his shop. He advertised his services, and the cigars he stocked for his patrons, in the local papers, and when he died in August of 1865 the Quincy Whig noted “An Old Resident Gone,” and that his funeral would take place from the A.M.E. church, on the anniversary of his emancipation.

Berryman Barnett appeared before court clerk Henry H. Snow on Sept. 29th 1833 to present his “deed of emancipation.” In it John Barnett of Bowling Green, Pike County, Missouri stated that “for good and lawful causes . . . and for and in consideration of the sum of one hundred dollars lawful money, of the United States,” he was granting to Berryman “his personal freedom from me, my heirs and assigns forever, . . .” His testimony also granted to his former slave “all such sum or sums of money, goods, chattels, lands and tenement as he the said Berryman shall hereafter acquire, to have and to hold, use, occupy, and enjoy the same. . .”

Berryman Barnett would become a resident of Quincy and an active participant in the local Underground Railroad. It was he who guided the escaping slave “Charlie” to the home of Dr. Richard Eells in 1842.

William Henry Brown appeared before Henry H. Snow on April 15th 1837 to register his freedom papers, which contained a most touching declaration by his father William Brown, of Washington, District of Columbia. “To wit To whom it may concern be it known that I William Brown . . . for and in consideration of the natural love and affection which I have and bear to my son William Henry Brown and for diverse other good causes and considerations, and me thereunto moving, and also in consideration of the sum of one dollar to me in hand paid by the said William Brown have released from slavery, liberated, manumitted and set free. . . my son William Henry Brown about the age of twenty years and able to work and gain for himself a good and sufficient livelihood and maintenance.”

Now, nearly two hundred years after they were entered, these records in the Adams County courthouse bring to our attention men, women and children who passed through Quincy, and a small portion of their life history. They also provide a rare glimpse into some of the challenges faced by these people of color who, while technically “free,” continued to live in a nation which would not afford them the full privileges and freedoms of citizenship until many decades after a war had been fought between North and South.

Sources

Adams County, Illinois. Circuit Court Records, Vol. B. 1826-1844.

Ankrom, Reg. 2014. “Failure of Tillson’s combine bankrupts Second State Bank.” Once Upon a Time, Quincy Herald Whig, 27 July, 2014.

Bangert, Heather. 2020. “Quincy’s Location Key to Flourishing Anti-slavery Network.” Once Upon a Time, Quincy Herald Whig, February 2, 2020.

Blackwood, James. 1972. Quincyans and the Crusade Against Slavery: The First Two Decade, 1824- 1844. Quincy, IL: Blackwood Enterprises.

City of Boston, Archives and Records Management Division, Guide to the House of Industry Records.

Constitution of the State of Illinois, 1918, Section VI.

First General Assembly, State of Illinois, AD 1819. No. 722 Box 21. “An Act Respecting Free Negroes, Mulattos, Servants, and Slaves.”

“An Old Resident Gone.” Quincy Whig, August 5, 1865, p. 3.

Quincy City Directory, 1857, p. 79.

“William Foote, the Barber.” Quincy Whig, September 8, 1847, p. 3.