New Philadelphia: Free Frank McWorter and the Clark family's fight for freedom

The Fugitive Slave Act passed Congress as one of five bills in the Compromise of 1850, and now Quincy's abolitionist network was in greater danger operating secret routes for runaway slaves. Missouri and southern slave-owners could now travel to free states and retrieve their human property by any means necessary, with federal laws justifying their oppression.

Runaway slaves and free blacks living in Illinois in 1853 were further disheartened by passage of a clause in the Illinois Constitution that required a large fine for any person who brought free blacks into the state, or arrest and deportation for an emancipated black person who arrived alone. It was also illegal for a slave-owner to bring their slaves into the state for the purpose of freeing them.

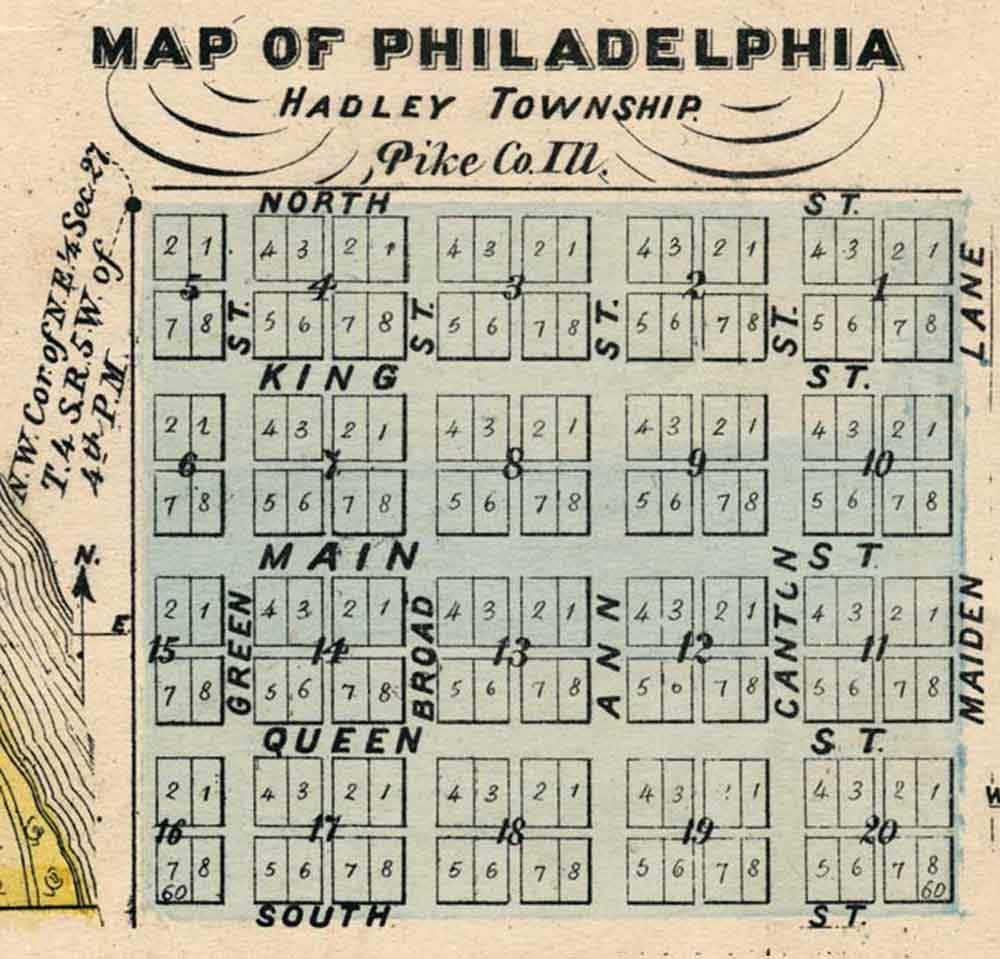

‘Free' Frank McWorter, a free black man who founded New Philadelphia, was markedly affected by the new laws. Frank and other former slaves lived in the town about 30 miles south of Quincy in Pike County. He had purchased his wife Lucy's freedom from slavery in 1817, his own freedom in 1819, and several family members until emancipation. He had worked for several years in Kentucky as a free man before moving to Illinois in 1830. Juliet Walker, Free Frank's biographer and great-great granddaughter, theorized about his motives when founding the town. She wrote "his purpose in establishing New Philadelphia had been to provide a place of settlement not only for his family as he purchased them from slavery, but also for other blacks who might want to settle in Illinois."

Frank died in 1854, followed by his son Squire in 1855, and their departures in addition to the new oppressive laws may have persuaded one New Philadelphia family, the Clarks, to take more drastic measures against slavery. By 1855 Keziah (Cassia) Clark, originally from Kentucky, moved to Quincy with her daughter Louisa and three sons, Simeon, Monroe and William Clark. They had previously purchased land in New Philadelphia, including one lot in 1854 owned by Free Frank.

Clark's eldest daughter Louisa had married Free Frank's son Squire McWorter in 1843. Squire had helped his wife escape to Canada until his father could buy her freedom in Kentucky. Louisa, her mother, and her brothers all lived in the same Quincy neighborhood in residences on Third Street between State and Delaware. Two of her brothers, Simeon and Monroe, worked for John Van Doorn, whose antislavery work is documented. The brothers worked on the riverfront, laboring at Van Doorn's sawmill while secretly organizing a route to Canada for runaway slaves in their spare time.

Simeon was an engineer and sawyer, while Monroe was a laborer who likely utilized his blacksmithing experience. William worked for Sylvester Thayer's distillery which was next door to Van Doorn's sawmill. The McWorter and Clark family's involvement with Quincy's antislavery crusade made this section of western Illinois a more efficient and organized Underground Railroad route. Frank and his family knew the route to Canada from Kentucky by the mid-1820's, as Free Frank's son Young Frank escaped to Canada when his master threatened to sell him before his father earned enough funds to emancipate him.

On Leap Year Day 1860 the Quincy Herald accused John Van Doorn of encouraging other people to go across the river to Missouri and entice slaves into leaving their owners, and once they were on the Illinois side of the river, helping them flee north. The country was dividing, and this was especially true on the western edge of Illinois, where slavery had already extended to neighboring Missouri and was threatening to spread to Kansas and beyond. The Herald reminded Van Doorn his actions were illegal, and compared his crimes to the lynching of abolitionist Frederick Schaller in La Grange, Mo., of which Van Doorn complained.

As the threat of war increased, this region sometimes faced hostile opposition among citizens. Clarissa Shipman of Pike County wrote to her family of "stirring times around here lately ... half a dozen of our neighbors caught four fugitive slaves from Missouri and carried them back to their masters, for which it is said they got $1200 ... There seems reason to believe that the fugitives are enticed to flee here. They come as far as Barry, as if they are among friends. There they were set upon and returned. I think we have fallen on evil times."

Another letter from Shipman reflected the growing tension in Adams and Pike Counties: "There are secessionists in the neighborhood," she wrote. "One of them is C. Staats, who is a rabid one. It would go hard with us if he had his way. He has expressed his views fully, said he wanted to get a shot at a few of his Abolitionist neighbors. It is said that he keeps three loaded guns by his bed. But Dr. Baker gave him to understand he was being watched and should any mischief occur he would fare hard. I think it frightened him."

During the Civil War, Simeon Clark became a soldier for the Union Army in the 38th U.S. Colored Infantry. He returned to Quincy when the war ended, then later moved to Kansas with two brothers. Keziah, Louisa, and other Clark family members returned to New Philadelphia.

In 1870 Simeon Clark and John Van Doorn united with other Quincy citizens who supported equality. The 15th amendment had just passed and a celebration among citizens of Quincy who had supported the antislavery stance before the Civil War was being organized. The new Amendment stated that the right to vote by citizens of the United States shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude.

At this meeting Clark described working the UGRR in the 1840's. He described "how he had, time and again, assisted his flying brothers from the pursuit of the negro-hunter and his bloodhounds. He drew a graphic picture of the condition of things then, and their now happy termination." John Van Doorn also spoke a few words. His antislavery involvement had been through action, and he had never spoken publicly until this meeting.

The grand celebration was held on April 16, 1870, with a procession beginning at A.M.E. Church at Ninth and Oak. Over a thousand citizens of African ancestry, including some former slaves, marched several blocks to Pinkham Hall near Third and Maine. The procession included 30 young girls dressed in white, horsemen, and many flags and banners. Large banners with portraits of President Abraham Lincoln and Civil War Gen. Ulysses S. Grant were displayed to honor the men who helped emancipate millions of their countrymen.

At Pinkham Hall Simeon Clark took the stage and addressed the crowd. More pictures of Lincoln and Grant were placed in the foreground, and the afternoon was filled with speakers, music, and prayer by A.M.E. Pastor E.C. Joiner. The Whig covered this event and printed: "A few years ago such justice would not have been tolerated. Truly, the world moves. Light is breaking."

Heather Bangert is involved with several local history projects. She is a member of Friends of the Log Cabins, has given tours at Woodland Cemetery and is an archeological field/lab technician.

Sources

Quincy City Directories, 1855-1870

Quincy Herald, Feb. 29, 1860.

Quincy Whig, April 1870.

http://www.findagrave.com/cgi-bin/fg.cgi?page=gr&GRid=18265359

http://www.histarch.illinois.edu/NP/44-1-7.pdf

Cahill, Emmett. The Shipmans of East Hawaii. University of Hawaii Press, 1996.

Shackel, Paul A. New Philadelphia: An Archeology of Race in the Heartland. University of California Press, 2010.

Walker, Juliet E.K., Free Frank: A Black Pioneer on the Antebellum Frontier. University Press of Kentucky, 1982.