Gem City Business College educator saved American bluebird

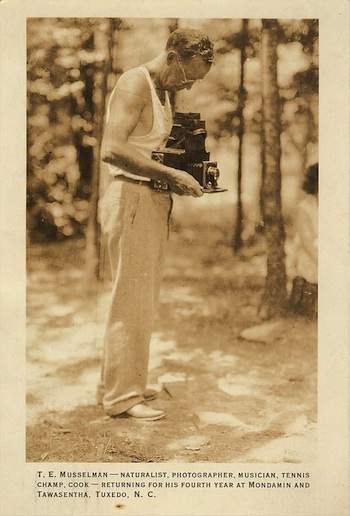

Thomas Edgar Musselman was as unique as the college his grandfather founded in Quincy in 1870. An accomplished educator and college athlete, Musselman’s reputation was earned for his successful work to save the American bluebird.

T.E. (only his closest friends called him by his first name) and his brothers D.L. and V.G. were officers of Gem City Business College, established in 1870 by their father DeLafayette Musselman. In college directories the Historical Society of Quincy and Adams County owns, the institution claimed to dominate commercial training in the Mississippi Valley. The 1940-41 issue, for example, boasts testimonials of success from several graduates, including the undersecretary of the U.S. Treasury D.W. Bell and the U.S. Commissioner of Accounts and Deposits Edward F. Bartelt.

Enrollment that year approached 700.

The college fielded intercollegiate sports teams, a drama club and honored

students for penmanship.

Musselman was secretary of his family’s degree-granting

business college in a five-story building that dominated the streetscape at

Seventh and Hampshire. He had earned bachelor’s and master’s degrees at the

University of Illinois, where he was a champion tennis player, and received an

honorary Doctor of Science degree from Carthage College. He was elected the

first president of Kappa Delta Pi, a national education honors fraternity he

helped found.

It was his other calling, however, that earned Musselman an international reputation. His interest in natural history and his personal study of birds led to discoveries the International Audubon Society has credited with saving the bluebird in America.

While an undergraduate at Illinois Musselman was involved in groundbreaking studies of natural history. As a graduate student he enrolled in the university’s first course in ecology. By then an inveterate student of nature, Musselman planned to teach and continue his research at the university. He was summoned, instead, to return to his family’s college While Gem City Business College provided his livelihood, Musselman filled the next seven decades of his life satisfying his personal interest in the world around him. His focus was on its birds.

Musselman became a popular lecturer on natural history around the region. His talks were lively, his gestures capable of imitating “the boundless energy of a chickadee and the menacing gestures of a snake. . .” and his stories capable of creating pictures of life in hedgerows and weeds. For most of the students of three generations, a biographer wrote, “T.E. Musselman was the one assembly of the year which no one wanted to miss.”

He was a favorite of children in the neighborhood of his 24th and Maine Street home. He introduced them to the bats and ghost-like invertebrates—white and blind because they never saw light—that lived in the water-carved limestone that formed Burton Cave east of Quincy. In the blackness of the cave at the end of the tour, Musselman raised the hair on the necks of his young guests in his slow, deep-throated recitation of “The Hounds of the Baskervilles.”

In 1921 Musselman wrote one of the first surveys of the birds of Illinois in 1818, the year of statehood. He described hawks and horned owls, bullbats and blue herons, Carolina Paroquets and Prothonotary Warblers. He studied the “vehement notes” of the Chickty-beaver Bird, and he concluded that the sound of the Henslow Bunting was a faint imitation of the Dick Cissel’s song.

Musselman’s observations led to alarm in the early 1930s that the population of bluebirds in Adams County was seriously declining. His response was a decades-long study of the American bluebird. Observations — and data he collected from them — revealed to Musselman the key reasons the bird was losing out:

• Farmers had begun replacing wooden fences, in whose holes the bluebirds nested, with wire and steel.

• Dead wood the bluebirds found comfortable for nesting was being pruned by nurserymen from orchards and woods.

• Fewer woodpeckers were hewing out holes.

• Brutish sparrows and starlings were intruding.

The consequence was fewer places in which bluebirds could nest.

Musselman started experimenting with ways to bring back the bluebird. It was his observation of a cavity that a downy woodpecker had carved in an old willow stump that led to his idea to create nesting boxes for bluebirds. Over the next eight years he built nearly a hundred experimental boxes of various shapes and sizes, copying the woodpecker hole as closely as possible.

He fixed the boxes to trees and posts along county roads and highways in what he called trails. His granddaughter Gail Harmeyer recalled that Musselman would drive from bird house to bird house, check each of them and wash out each of them. Occasionally, she remembered, he found a cowbird had invaded the nest. The cowbird’s eggs hatched sooner and as the chick grew it starved out the baby bluebirds.

“If he found cowbirds he would pitch them out,” Harmeyer said. “He took care of those trail boxes until he couldn’t walk anymore.”

Musselman’s detailed study indicated the birdhouse’s best placement was near a field or pasture at three to four feet above the ground and facing east or south. His experiments disclosed the most effective hole size, cavity depth and interior dimensions, ventilation and drainage. His study produced new findings on reproduction, predators and the occurrence of abnormalities.

Dozens of boxes and ultimately a thousand “Trail Boxes” were placed along roads that fanned out from Quincy into Adams County. Musselman’s campaign to save the bluebird won the interest of Boy Scouts and garden clubs, whose members took up the cause of saving the bluebird. The Boy Scouts recognized Musselman’s contributions to young men’s citizenship and interest in conservation, awarding him the Silver Beaver, scouting’s highest honor. And the International Audubon Society noticed his crusade, which grew nationwide, and credited Musselman with saving the bluebird in America. He continued his research, which his family donated to the University of Illinois, and it is recognized as the basis for much of the knowledge of the habits of America’s bluebirds.

With interest growing across the country, Musselman formed a partnership with J.L. Wade of Griggsville for the production of the bird houses. Wade was doing similar work to restore the habitat for the Purple Martin, and Musselman’s “Bluebird Trail” column appeared regularly for several years in Wade’s nationally circulated Purple Martin Capital News.

Born April 28, 1827, Musselman died June 12, 1976. He would have known that by that date, American bluebirds had just finished their first mating of the season.

Reg Ankrom is executive director of the Historical Society. He is a member of several history-related organizations, the author of a history of Stephen A. Douglas and a frequent speaker on pre-Civil War history.

Sources" A Record of Seventy Years of Service to the Young People of America." Gem City Business College, Quincy, Illinois, 1940 1941. Historical Society of Quincy and Adams County Research Library. Gail Harmeyer (T.E. Musselman granddaughter). Interview by Reg Ankrom, September 20, 2011. Hunter, Hon. Robert S (Musselman boyhood neighbor). Interview by Reg Ankrom, October 13, 2011. "Musselman Houses," Bluebird Journal of the North American Bluebird Society, Bloomington, Indiana, Spring 1999. Musselman, T.E. "History of the Birds of Illinois," Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society. Springfield, Illinois: Illinois State Historical Society, 1921. Salisbury, Beverly Newsom. "Granddaughter of Famous Bluebird Researcher Lives in HSV," The Chirp. Hot Springs Village, Arkansas: HSV Audubon Society, Autumn 2011. "T.E. Musselman," Bluebird Trails. Coeur d'Alene Audubon Society, http://www.cdaaudubon.org/November2004.htm