Illuminating history on Quincy's Red Light District

From illuminating scraps of history, stories abound that add dimension to the roots of our river community. The good and celebrated, the bad and appalling, and the ugly and unspoken are all part of a shared identity.

Reflected in the headlines of the community record the news reported the mundane and the salacious. In the early 19th century the Mississippi River was emblematic of opportunity. Shortly after Illinois became a state in 1818 and the Military Tract bounty land became available, John Wood and Willard Keyes bought land in what they deemed a perfect spot on the Mississippi.

Quincy, referred to as “Bluffs” for many years, was a key spot on the upper Mississippi where the water met the bluffs as an ideal port for steamboats, trading and commercial prospects. Within a few years the riverfront bustled with passengers, porters, tradesmen and speculators. The waterfront also became an intriguing blend of those with purposeful pursuits and carousing folks who hung out by day and night.

Odd characters, stated an early Quincy history, “always succeeded whenever they chose in giving a carminal (red) tint to the town of the most original and ruddy hue.”

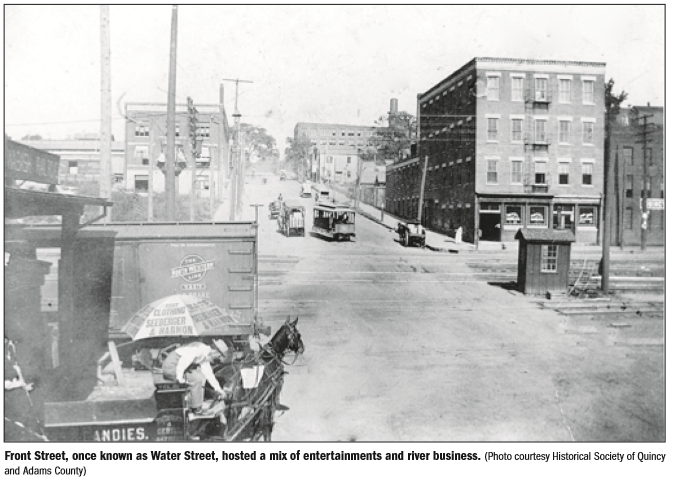

Steamboats and Burlington railroad depot erected in 1864 brought to Front Street a spirited mix of entertainment and river business. Front Street, at one time known as Water Street and later “The Levee,” was a mix of dry goods stores, saloons, hotels and restaurants. Before and after the turn of the century saloons such as the Jefferson Renfrow Great Western Saloon and the Olive Branch Saloon and hotels such as the Steamboat Hotel, the Pacific Hotel, the Sherman House and the notorious New Orleans represented vigorous business activity.

Early settlers of great energy and enterprise sought to build a thriving community and a better life. Quincy became home to a number of the finest pioneer leaders in business, law and trade.

Alongside these forces seedy indulgences prevailed. Social gathering establishments grew and prospered. From this amalgam of activity longstanding social vices multiplied at the water’s edge. Disguised by front rooms, front people and a lively burlesque nightlife, riverside bordellos generated a booming river culture. Centered near the waterfront at the foot of Oak Street the initial red light district flourished for decades.

From the beginning of municipal government the red light district was legalized by the city council. When the railroad depot was constructed at Second and Oak in 1899, most bordellos were razed and many houses on Maine, Hampshire, Vermont, Broadway, Spring and Oak streets were taken over by “ladies of the night.” Unhampered by authorities, there were “50 brothels on Maine below Third Street” at the turn of the century. Shortly after this time, aldermen voted to fix the district’s limits at the river, Third Street, Vermont and Broadway. The hub of Quincy’s well-known and longstanding “famous line of vice” was at Broadway and Second.

Finally by 1918 local officials were calling for an end to such longstanding practices.

Eight years earlier James R. Mann, an Illinois congressman, introduced an act known as the Mann Act or the White Slave Traffic Act, a federal criminal statute to protect those being forced into prostitution. The term white slavery described predicaments vulnerable females faced. The Mann Act also was used to prosecute men who took women across state lines for consensual sex.

Eleven brothels remained in Quincy in 1918 and police raid reports at times cited the names of the city’s best known ladies, along with the dame who ran each house. The newspaper reported that particular houses were “nearly always visited by famous out-of-town criminals.” In reference to stories about women of ill-repute newspaper articles published between the years 1907 to 1918 used what have become outmoded euphemisms. The women were referred to as inmates or inmates of “sporting resorts” or an inmate of Jane Smith’s “sporting establishment.” A red cloth over the transom signaled services available and the term “red transom district” or “tenderloin district” were popular orientations to the areas of town. Headlines like “Police Raid a Broadway Resort,” “Red Transom District Raid” and “Naughty Girls Fined $5 each” were common.

In 1918 public spirited citizens wanted change. A story in the Quincy Daily Journal declared that Quincy’s famous line must go after 50 years of “deadened public sentiment” on social evil. Newspapers reported that public sentiments were at “white heat.” Aldermen Samuel S. Hyatt called upon Mayor J.A. Thompson and Chief of Police Louis N. Melton to enforce the state and city laws against prostitution. The full reading of Hyatt’s resolution was printed in the paper and editors stated it “is expected to pass the council by a unanimous vote. It is not believed that in the face of crystallized public opinion, any alderman will take his political life in his hands by voting against the measure.” Mayor Thompson declared “the time was ripe for action” and in one of the “shrewdest political maneuvers in the history of Quincy,” said the paper, Mayor Thompson took away from Alderman Hyatt the credit of the resolution and announced that he already had abolished the red light district and its 11 houses on lower Broadway and Vermont by an order to take effect July 1.

Charges of political maneuvering were thrown back and forth. One June 30, 1918, Quincy’s colony of prostitutes was officially ended after 60 years. Though new laws went on the books, enforcement was notably absent. Even after city, state and national attention focused on prostitution in the Tri-state are, practices continued. “Sporting resorts” in Quincy remained in operation and court cases surfaced as a result.

Nearly 20 years after the repeal of the permissive law, an April 5, 1838, newspaper headline, for example, read: “... a white slave case defendant describes operation of Murray Resort at 301 Vermont.” A long line of witnesses was placed on the stand on charges of violating the Mann Act. The line of questioning was chronicled in the newspapers for all to read. The resort keeper and three others were found guilty of the charges, notably for transportation of women to Quincy from other states. Eventually, taverns with “girls in the back,” businesses with “girls upstairs” and gambling dens crept into the shadow of the Adams County court house.

Illicit practices flourished and houses remained unrestrained in the district except for an occasional raid. The seedy side of life had a strong hold in the community during the colorful years of the Roaring ‘20s. Official crackdowns continued sporadically through Prohibition years and decades beyond. Our river town gained a reputation as “Little Chicago.”

Civic-minded people worked to clean up its rough underworld, especially after particularly ugly aspects of our checkered past regarding local gambling corruption made the headlines of Collier’s magazine, a respected national publication, just over 60 years ago.

The history of the red light district in Quincy and the criminal world of gambling and gangsters that flourished alongside respectable merchants and residents is part of the oral history of the community. However, it is not written on the pages of local history publications. Nevertheless, the facts were chronicled in the public record and add to the multifaceted social history of our town and its evolving character.

Iris Nelson is reference librarian and archivist at Quincy Public Library, a civic volunteer, member of the Lincoln Douglas Debate Interpretive Center Advisory Board and other historical organizations. She is a local historian and has authored articles in historical journals.

Sources:

"Choir Girl in Tenderloin," Quincy Daily Journal, August 1, 1907.

" ... Convicted by Jury in Federal Court on Charges of Conspiracy, White Slavery: Howard Murray Found Guilty on Three Counts Together with Virgil Mayberry, Phyllis Hatfield and Clarice Burham; Verdict Returned Friday Night," Quincy Daily Journal, April 9, 1838.

"Fight in the Red Transome (sic) District," Quincy Daily Journal , April 12, 1907.

"Hyatt To Ask Aldermen to Abolish Line," Quincy Daily Journal, June 17, 1918.

"Julia J. Basford, White Slave Case Defendant, Describes Operation of Murray Resort at 301 Vermont," Quincy Daily Journal, April 5, 1838.

"Mayor Hastens To Abolish Red Light District," Quincy Daily Journal, June 18, 1918.

"Old Days Pass Forever Sunday When Line Ends," Quincy Daily Journal, June 29, 1918.

"Police Raid a Broadway Resort," Quincy Daily Journal, July 30, 1913

"Red Transom District Raid," Quincy Daily Journal, October 14, 1903.

Tillson, General John. History of the City of Quincy, revised and corrected by Hon. William H. Collins by direction of the Quincy Historical Society. [S.L.: s.n.], 1992.