Great Depression Turned Local Prosperity Into Plight

As the United

States entered the fall of 1927, the country’s economic prospects shined

brighter than in previous decades, with the relative prosperity of the “Roaring

20s” reaching from the financial capital of New York to Midwestern cities like

Quincy. Business in the Gem City had rarely been better, and many citizens had

a higher standard of living than at any time during the century.

A speech by prominent economist Roger Babson reprinted in the October 15, 1927, Quincy Herald-Whig proclaimed that by investing money in the stock market more people could participate in this national abundance. “There is nothing to be pessimistic about...Business, on a whole, is getting better and more stable with each generation, the world is constantly improving and in the long run the ‘bulls’ always make more money than the ‘bears.’”

Two years later, fueled by greed and over-speculation, the stock market collapsed. The worst economic crisis in American history, the Great Depression, began and would last throughout the 1930s.

Unemployment rose to staggering levels, and soon mortgage foreclosures and bankruptcies became so widespread that the city of Quincy appointed Joseph R. Morton as Master-in-Chancery to handle the flood of cases. As panic increased, banks refused loans to struggling individuals and small businesses. The bankruptcy of the Orchid Grill owned by James Morse at 834 South 8th St. in Quincy illustrated how tight money and credit policies wreaked even more havoc on the economy. With liabilities of $1,523 and assets of $300, Morse could claim a business exemption of $300 but needed a loan to stay afloat. Local banks refused, and his business—like many others in town—closed and never reopened.

The bankruptcy of the Broadway Brokerage Company, owned by Quincy residents Frank C. Gille and H. W. “Doc” Faulkner, created a scandal. Although their firm had recently received checks for over $29,000, it failed to pay creditors or distribute dividends. Attorney Richard Scholz served as trustee-in-bankruptcy and uncovered assets of only $12.68, 15 cases of chewing tobacco, and a metal filing cabinet. After being indicted in U. S. Federal Court in Springfield, Illinois, on five counts of fraud, Gille stated that the checks “had disappeared.” He and his partner were convicted and sentenced to Ft. Leavenworth Penitentiary in Kansas, but not before Quincyans lost more money and faith in the economic system.

Following the national trend, banks in Quincy began failing in 1930. The first were Ricker Bank at 415 Hampshire and the city’s largest financial institution, State Savings Loan & Trust Company. The problem became so critical that Judge Fred Wolfe, during proceedings, dismissed the Adams County Circuit Court jury because many jurors and attorneys had accounts embroiled in the failures. A dozen more banks in the immediate area soon failed.

Unemployment in Quincy by the summer of 1930 nearly reached the national level of 25 percent. Desperate for work, many people would take any odd job for a dollar a day or trade labor for food. In the June 17, 1930, Quincy Herald-Whig, Mrs. E. Jane Thompson, a secretary at Quincy’s Associated Charities, presented a stark picture of local poverty. “Many come to the office with shoes worn through, and their feet in pitiful condition from walking many miles in ill-fitting shoes, looking for work. Many are ill because of under nourishment, improper food and worry over lack of employment. Many are hungry.”

Across the city, soup kitchens sponsored by churches, charities, and individuals like Fred Werneth opened. A meat-maker operator at 606 Hampshire, Werneth served 300 gallons of soup and 300 sandwiches every week to the needy. Unitarian minister Rev. Daniel Sands established a “Neighborhood House” in an impoverished part of the city at 410 S. 4th. St. He and his wife lived there and provided social welfare programs and counseling, as well as food.

Homelessness became rampant, and itinerant “hobos” furtively rode the rails camping out wherever they could find shelter. Along Quincy’s Mississippi River Bay, hobo camps formed with colorful names like “Kelly’s Jungle” and “The Holy Hole.” Inhabitants scavenged for handouts, and during winter the city jail provided sleeping space for as many as 18 homeless men every night.

Despondency and desperation brought more tragedy into the community. A coroner’s jury failed to determine if the March 1937 gunshot death of George Homkey, a homeless man staying at the Salvation Army, was suicide or murder.

Women suffered inordinately as divorces rose to unprecedented levels. In most states, only husbands could legally bring suits—except in cases of adultery or bigamy—and after a divorce, women were often left without resources. Since unemployment rates did not include females, agencies made little effort to find them jobs and employers were reluctant to hire them.

The divorce of Rev. Celian Ufford, the former minister of Quincy’s Unitarian Church, now living in Massachusetts, made front-page headlines in Boston. Mrs. Ufford’s claim that her husband and another man had assaulted her went unheeded while the case proceeded on the minister’s grounds of his wife’s “cruel treatment”—behaving in a manner unbecoming of a clergyman’s spouse.

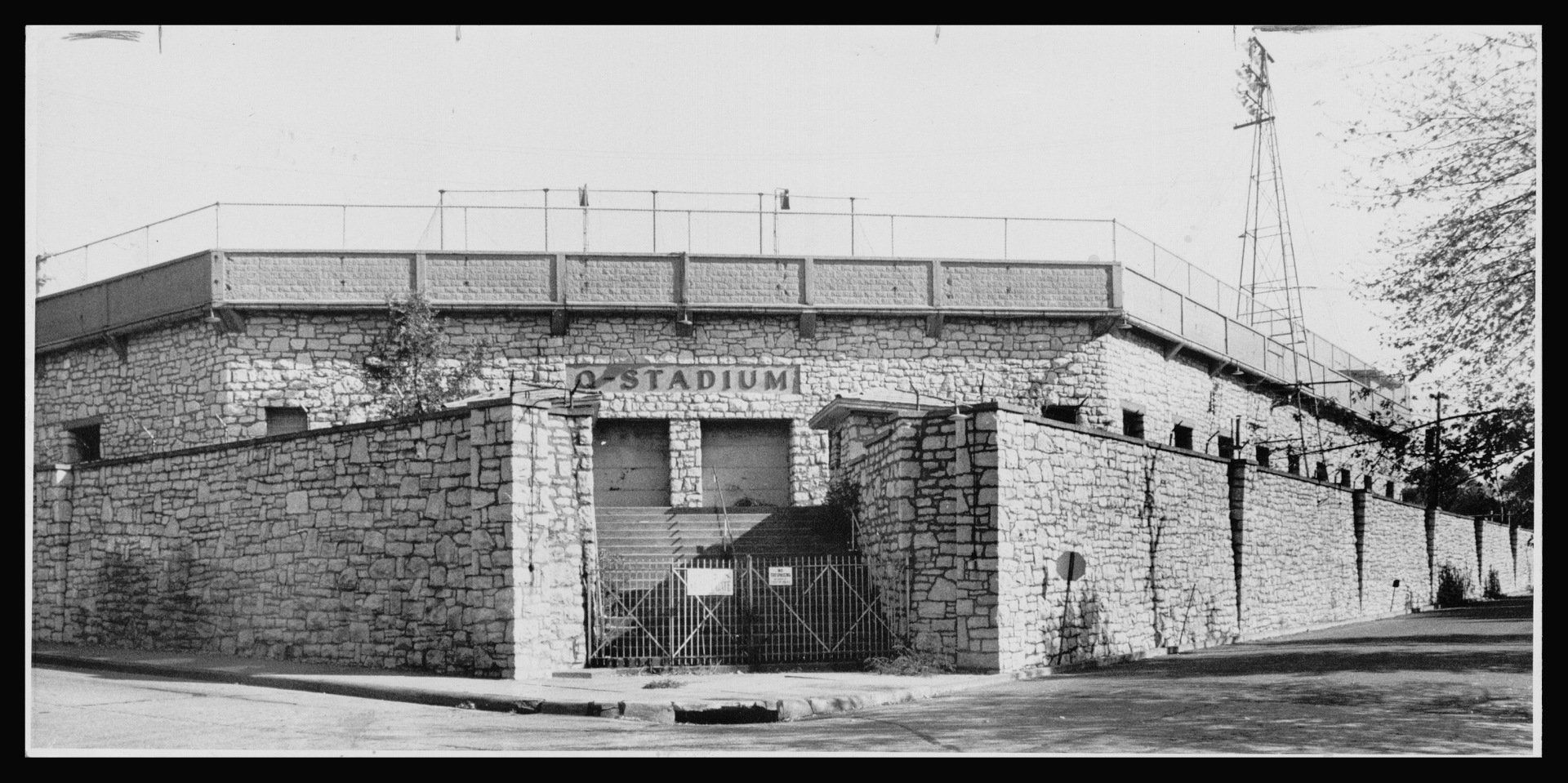

Most historians believe that President Franklin Roosevelt’s “New Deal” of government programs started in 1932 began the country’s emergence from the Great Depression. The Works Progress Administration (WPA) alone hired 8.5 million unemployed and mostly unskilled young men to build roads, parks, and public buildings. In Quincy, the WPA built—among other projects—Q-Stadium at 18th and Spruce, roads through city parks, buildings at Soldiers and Sailors Home, and a stone perimeter around Quincy College.

Roosevelt’s New Deal would create forty-two new government agencies that provided millions of civilian jobs before the U. S. entered World War II in 1941 following the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. During the four years of the war, defense spending soared into several billions of dollars annually, and combined with soldiers deployed in the military effort and citizens supporting the war effort at home, the Great Depression effectively ended.

Sources

“Appeals For Help Show Quincy Has Jobless Problem.” Quincy Herald-Whig , June 13, 1930, 18.

“Babson Outlines Reasons Why Stock Market Stays at Present High Average.” Quincy Herald-Whig, Oct. 15, 1927, 4.

“Brokerage Firm Bankruptcy in Federal Court.” Quincy Herald-Whig , March 13, 1935, 14.

Collier, Christopher. Progressivism, The Great Depression, and The New Deal. Salt Lake City, UT: Benchmark Books, 2001.

“Cruel Treatment Basis of Ufford Suit for Divorce.” Quincy Herald-Whig , Nov. 10, 1929, 22.

“Jury Discharged in Circuit Court, Cases Postponed.” Quincy Herald-Whig , Nov. 17, 1930, 12.

“Much Work Done By CCC Labor in Adams County.” Quincy Herald-Whig, March 29, 1936, 2.

Terkel, Studs. Hard Times: An Oral History of the Great Depression. New York: Pantheon Books, 1970.