Great Influenza Epidemic of 1918 took its toll on Quincyans

In the autumn of 1918, with the U.S. military engaged in the Great War (later known as World War I) raging in Europe, doctors and nurses at home were fighting another war that would eventually claim 15 times as many civilian American lives as all U.S. soldiers dying in combat.

The Great Influenza Epidemic of 1918 -- and the disease's resulting pneumonia -- was the most deadly plague in modern history and during its trajectory depressed the life expectancy of U.S. citizens by 10 years. As the death toll dramatically rose, undertakers in some parts of the nation ran out of coffins and had bodies piling up. Gravediggers, fearful of infection, boycotted work. Moreover, military commanders inflamed its lethal affect by ignoring hygiene precautions and jeopardizing the health of soldiers.

Crowded wartime barracks, bivouacs with ill-suited sanitation and trenches where rats often outnumbered men hastened transmissions among soldiers. Returning combatants brought the illness back to civilians; newly drafted civilians brought the illness back to soldiers. Unlike other influenza outbreaks, this one targeted and killed mostly young people in the prime of life with a three to four times greater mortality rate. Infections coursed through bodies so fast that they often proved fatal within 24 to 48 hours of onset.

Three native sons training for war at Illinois' Great Lakes Naval Base became the Quincy area's first fatalities: Harry Riggs Jr., Harry Lamb and Charles Pritzlaff. Several thousand illnesses and about 500 deaths would follow in military and civilian life. Local papers published the names and addresses of sick people and often gave detailed accounts of their illness and prognosis.

The Quincy Daily Herald on Oct. 22, 1918, reported: "The condition of Mrs. Marguerite Kiely remains the same today. She is growing steadily weaker and it is thought that her death is only a matter of a few days." On Oct. 18, 1918, a couple in their early 30s, Mr. and Mrs. William Westenfeld of 1119 Jackson, died within 11 hours of each other, leaving their two young children orphaned.

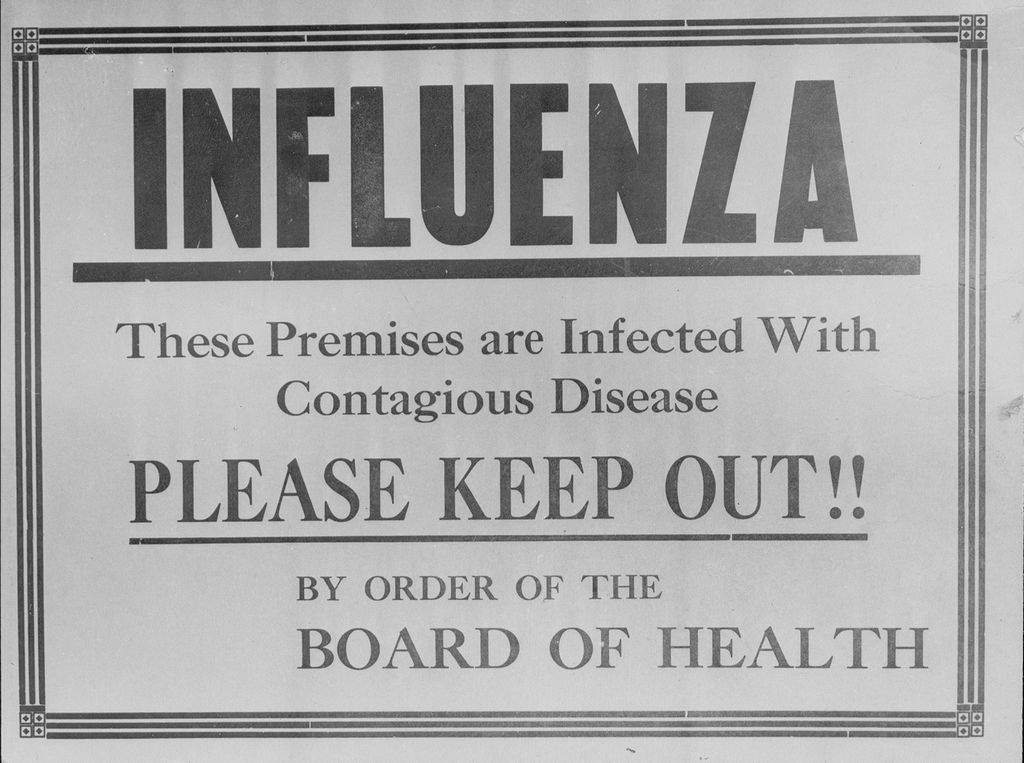

Quincy set up emergency hospitals on 16th and Vermont and at the John Wood Mansion on 12th and State after St. Mary and Blessing hospitals could no longer handle incoming patients. Doctors inoculated all Adams County draftees (later proved to be ineffective) and local officials hung warning signs on sick people's doors and canceled all public meetings -- including schools and funerals. Public proclamations to quell panic appeared: "Fear is our worst enemy. The man who worries is half-beaten whether he fights a German or a germ."

Still, at the apex of the epidemic, Quincy ambulance drivers refused to handle influenza victims.

As illness and death swept over the region, so did anti-German sentiment, with the Great War's enemy and the insidious spread of influenza merging. After Camp Grant, where many Quincy soldiers trained, experienced a massive outbreak of the disease, The Quincy Daily Herald on Oct. 5, 1918, had this headline: "Even Influenza Won't Touch the Boches" (a contemptuous term for Germans). The story stated, "Influenza has affected all ranks of the 40,000 men at Camp Grant, but has declined to enter the barbed wire in-closures where the German prisoners are herded." Many people believed that Germans had planted the disease in American soldiers and in soil.

Contemporary medicine, though, considered influenza a bacterial disease -- viruses had not yet been discovered -- and this shaped local public policy. Sanitation workers flushed streets, stores fumigated and disinfected their premises, saloons stopped serving free lunches, the city set a curfew on children under 16, and after a recommendation by the Quincy Health Board, the city council legalized leaf burning as a way to ward off germs. Official precautions against contracting influenza included avoiding kissing, coughing, sneezing and spitting (of saliva and tobacco) in public, burning or disinfecting of handkerchiefs, wearing gauze masks, eating plain food and avoiding alcohol, ventilating rooms with fresh air, and keeping feet warm and bowels open.

Commercial "cures" soared locally: iodine, creosote, Oil of Hyomel, sarsaparilla, Salinos bowel purgative, honey-tar concoctions and, during this epidemic, Richardson-Vicks Inc. introduced its decongestant Vaporub. Many Quincyans turned to home remedies: wearing a sachet of garlic or skunk oil around their neck, avoiding eye contact with strangers, sucking on hard candy and drinking whiskey.

After a committee on influenza advised Mayor John A. "Bud" Thompson, he considered quarantining the city when 1,843 cases were reported from Sept. 29 to Nov. 13, 1918. Health Commissioner C.L. Martin closed a candy factory, two parish schools and two restaurants for poor sanitation. On Oct. 10, Quincy Public Schools shut down for five weeks, the longest span in its history, but on the first day of reopening still reported 1,129 absences.

The Great War ended on Armistice Day, Nov. 11, 1918, but influenza continued for the rest of the year and into the early part of the next one. Although on the first day of peace the disease was waning nationwide, during the following week St. Mary Hospital reported 150 cases of influenza, with 22 of them fatal and seven of those within 24 hours of admission. The Great Influenza Epidemic, though, subsided by the spring of 1919 but not before it had claimed about 675,000 lives in the United States. In the Quincy area it sickened several thousand people and killed about 500 -- most of them young.

In the aftermath of the epidemic, the Quincy City Council funded a health commission with a staff of full-time nurses and food inspectors, policemen strictly enforced the spitting ordinance, and the Quincy Board of Education banned the use of a common drinking cup from a shared water bucket in classrooms. Amid fears of a returning epidemic, the city continued to allow leaf burning and local advertisements teemed with "After Influenza" patent medicine testimonials. During the following years, farmers bemoaned the spread of "flu" into their hog herds and the embalming of corpses, considered by many a vanity and needless expense, became more commonly practiced and perceived as a way to prevent another epidemic.

Joseph Newkirk is a local writer and photographer whose work has been widely published as a contributor to literary magazines, as a correspondent for Catholic Times, and for the past 23 years as a writer for the Library of Congress' Veterans History Project. He is a member of the reorganized Quincy Bicycle Club and has logged more than 10,000 miles on bicycles in his life.

Sources:

"A Sick List" Quincy Daily Herald, Oct. 22, 1918, p. 7.

"All Will Be Inoculated." Quincy Daily Herald, Oct. 25, 1918, p. 5.

Barry, John M. The Great Influenza: The Epic Story of the Deadliest Plague in History. New York: Viking, 2004, pref. 8, 131-2, 223, 239.

"Dread Malady Claims Young Married Couple." Quincy Daily Journal, Oct. 19, 1918, p. 10.

"Even Influenza Won't Touch the Boches." Quincy Daily Herald, Oct. 5, 1918, p. 10.

"Forget the Influenza." Quincy Daily Herald, Oct. 14, 1918, p. 3.

"Iodine, Creosote Cure Influenza, Physician Says." Quincy Daily Journal, Oct. 12, 1918, p. 6.

Kenner, Robert. Influenza, 1918: An American Experience. (video recording) PBS Home Video, 2005.

"Report Few New Influenza Cases." Quincy Daily Herald, Nov. 14, 1918, p. 4.

Silverstein, Arthur M. A History of Immunology. San Diego: Academic Press, 1989, p. 307.

"State Takes Steps to Stop the Epidemic." Quincy Daily Journal, Sept. 28, 1918, p. 2.