Pioneering pilot's missions carried her skyward

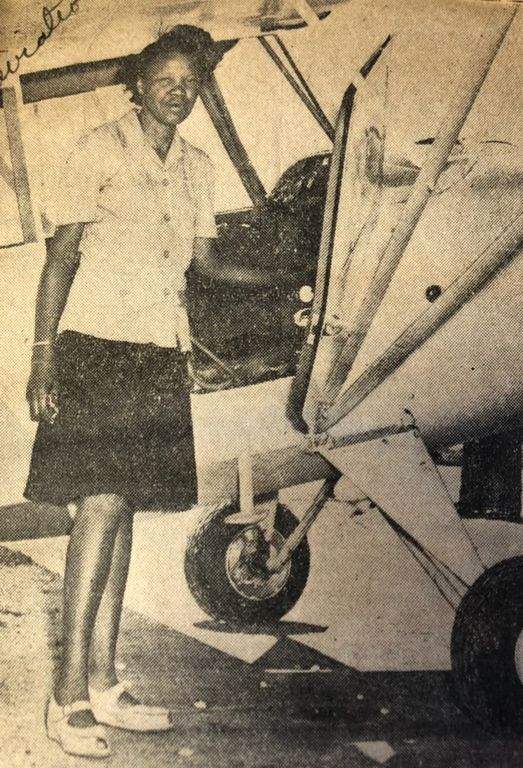

The Aeronca Champion's Continental four-cylinder engine rattled the light airplane to life. Twenty-seven-year-old Creadell Johnetta Haley had dreamed of this moment from the day she saw an airplane soar above her, a child who had just moved to Quincy from Pawhuska, Okla., in the 1920s. Firmly strapped in and alone at the plane's controls, Haley felt the fulfillment of her desire. Her instructor on that day, June 25, 1946, had approved her first solo flight.

Haley's parents had divorced, and Birdie and Nathaniel Haley, her aunt and uncle, raised the girl and her older brother, Nathaniel, on South Eighth Street. Graduating from Quincy High School in 1936, she waitressed at a Quincy restaurant until World War II began. Flying was never far from her mind, and when Congress created the Women's Army Air Corps on May 14, 1942, Haley enlisted Sept. 2. She was the first woman -- and the only African-American woman -- from Adams County to serve in the WAACs. She trained at Fort Des Moines in Iowa. At Fort Huachuca in Arizona, her skills as an auto mechanic won her a transfer into aviation mechanics. Although she did not get the opportunity to fly, Haley was discharged an aviation cadet and sergeant at the end of the war.

Returning to Quincy, she took flight instruction at the city's airport at 36th and Payson Road. She trained in the Aeronca, a tail-dragging high-winged aircraft so forgiving that it responded to a pilot's shortcomings like an admiring godmother.

On that late June day, Haley carefully performed her preflight inspection of the plane. When satisfied that its physical properties were airworthy, she climbed aboard and belted in. She peered out the window, intently scanning the area in all directions.

"CLEAR," she yelled through the open pilot-side window to draw attention of anyone in the area that she was about to start the engine. The yell was mandatory--to keep people clear of the propeller. Flight instructors often grounded students who forgot it.

Her belt fastened, the unmuffled engine howling, Haley worked her way down her preflight "runup." An acronym, CIGARS-T, led her through it. Check that controls are free; instruments--oil pressure and temperature--are working properly; check gas and altimeter; and runup at 1,500 RPM--magnetos and carburetor heat on--seat belts; and trim. Since Quincy was not a controlled airport, Haley tuned her radio frequency to the universal frequency, 122.1 Mhz. Finally, she corrected the plane's compass to compensate for a 2-degree west difference between true north and magnetic north. She overlooked one critical procedure: correcting for winds aloft.

The woman keyed her radio's microphone and announced the craft's identification number and planned direction to alert any other pilots in the area of her intention. Once again, she scanned the sky, then nosed the plane into the west wind and pushed the throttle all of the way into its seat. Pulling the stick gently back to bring up the tail wheel as speed increased, she had the Aeronca airborne at 48 knots at 2:30 p.m. Tuesday, June 25, 1946. A strong west wind pushed at the Aeronca's belly as Haley banked right to turn north.

Her solo flight, whose reward would be her private pilot's license, was to take Haley to Burlington, Iowa, and Macomb, Ill., airports, then return her to Quincy's airport by about 6 p.m. Her momentary error, however, would extend the flight well off course and send dozens of police and pilots searching for her.

Flying VFR (visual flight rules), Haley had placed in her lap a "sectional chart," an aerial map that shows topographical features such as terrain, airports and elevations, as well as rivers, railroads, towers and towns, landmarks by which to navigate. Haley had drawn a straight line on the sectional from Quincy to Burlington, a distance of 63 miles. Within the hour in which she had expected to reach Burlington, she realized that none of the landmarks below was matching up to the sectional chart. She knew she had drifted off course.

Haley dialed the radio to Burlington airport's frequency and reset the plane's omnidirectional range finder, a recently developed radio compass, to Burlington's signal. About an hour later, she spotted a river and an airport with paved runways beyond. She mistook what were the Illinois River and Peoria for the Mississippi River and the Burlington airport. That would exacerbate her error. Resting briefly and deciding she had enough fuel to make Macomb, 29 miles away, she took off again and flew by compass southeast.

The time of the second leg also went well beyond the distance to Macomb. Nearly out of fuel and with no airfields in sight, Haley made an emergency landing in an oatfield. She sought help at a nearby farmhouse and learned she was seven miles east of Clinton, nearly 100 miles off course from Macomb. She spent the night in Clinton.

The next morning, two local pilots gave Haley enough fuel to make the Bloomington airport, where she topped off her fuel tank and mapped a course back to Quincy. She had tried to call home but left before the operator could connect her. With one more stop for fuel in Jacksonville, she reached Quincy at 2:40 p.m. Wednesday, June 26. An observer described Haley, unaware of the excitement and searches she had caused when she went missing, as "unruffled."

Her pilot's license fulfilled a lifelong goal for Haley, but an even more heavenward passion, which she took with her to San Jose State College in California, became her greatest reward. Haley had found the Baha'i faith and a broadening belief in the oneness of man. It was her life's mission, and she became one of 13 Baha'i American Pioneers sent as missionaries to South America in 1968. Her greatest contribution to her faith was creating hymns of simple melodies and lyrics that were published and distributed around the world. Her four-chord "Baha'u'llah" has been recorded countless times and by numerous artists. It is available on YouTube atyoutube.com/watch?v=fnXjndNrvVw.

Pioneer Creadell Haley, 84, died Nov. 2, 2000, in Washington, D.C. She was buried in Quantico National Cemetery in Virginia.

Reg Ankrom is a former executive director of the Historical Society and a local historian. He is a member of several history-related organizations, the author of a history of Stephen A. Douglas, and a frequent speaker on pre-Civil War history.

Sources:

"A Baha'i Statement on Human Rights," National Baha'i Review. Wilmette, Ill.: National Spiritual Assembly of the Baha'is of the United States, April 1968.

Adams County, Ill., Archives Military Records, genrecords.net/emailregistry/vols/00025.html#0005998

Aeronca Champ 7AC Pilot Operating Handbook. Monroe, N.C.: Covenant Aviation, 2010.

"Council Provides Group Speakers," Spartan Daily, Feb. 24, 1959.

"Creadell Haley," 1920, 1930, 1940 U.S. Federal Census.

"Creadell J. Haley," U.S. World War II Army Enlistment Records, 1938-1946.

"Creadell Johnetta Haley: 1916-2000," ancestry.com.

Robert S. Hunter, Invitation to Flying: A Manual for Pilots. New York: Ziff-Davis Flying Books, 1979.

"Magnetic Declination Estimated Value," ngdc.noaa.gov/geomag-web/#declination.

Brenda L. Moore, To Serve My Country, To Serve My Race. New York: N.Y. University Press, 1996, pp. 4, 220.

"She Flew the Wrong Way," Quincy Herald-Whig, June 27, 1946. Father Landry Genosky Scrapbook 10, 23, Historical Society of Quincy and Adams County.

1920, 1930, 1940 U.S. Federal Census.

"WAAC Companies at Huachuca Recruited To Full Strength," Pittsburgh Courier, March 6, 1943, p. 10.