History of Hattie Dodd's building at Fifth and Maine

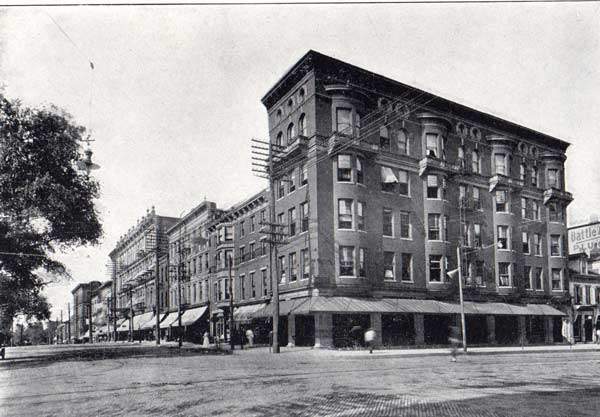

One wonders what Hattie Dodd would think today, standing on the northeast corner of Fifth and Maine, taking in her beautiful old building.

In 1878 Hattie C. Dodd married Dr. Charles. L. Koch, brother of George Koch who would become Quincy chief of police. The couple had been legally separated for several years when in 1897 she decided to replace an old building on the northeast corner of Fifth and Maine with a grand new one. By that time Hattie Dodd Koch had resumed use of her maiden name and had been living in New Orleans with her aunt and her daughter.

The previous brick structure, also owned by Dodd, was built in 1840 by Capt. Kelly, a railroad contractor. It was removed from the site and the new building began to rise. Newspapers quickly took notice, and The Quincy Daily Journal asked, "Where is there a building that rises with more stately dignity?"

Dodd had the five-story structure named in honor of her father, John Dodd. It was the tallest building in Quincy for 30 years and had the town raving when it opened to businesses, doctors, lawyers, and other professionals. For years it anchored the downtown square area. It was modern, elegant, and finely appointed from the mosaic floors to the hardwood paneling and state-of-the-art sound proofing in the partition walls, which were lined with mineral wool to deaden sound and hold in heat.

The structure was designed by Ernest Wood and cost $20,000 to build. The original dimensions were 100 feet on the Maine Street side, 24 feet on Fifth Street, and 70 feet high. In the early 1920s, after a fire, the building was remodeled and an addition built on the north side along Fifth Street, next to what is now known as the Schuecking's parking lot.

Bedford stone and Quincy pressed brick were used in the original construction, along with bay windows and other features to "break the monotony," as one newspaper put it. Every room in the building (except for the back area on the main floor) was reached by natural light. The building schedule was delayed for a time as brick demands for this edifice and the new Washington School, also under construction, were exceeding the output of the brick manufacturers in town.

Offices were originally arranged with three rooms each, with modern bathrooms and marble sinks. Only one marble sink remains, on the second floor. Gas and electric lights filled the building. Large transom windows were installed over doorways, and the well-walked floors made of yellow pine have withstood a century-plus of traffic.

The building itself was constructed by local businesses, and many of them left evidence behind, in addition to their construction. E. Best Plumbing and Heating did the plumbing, heating and gas-fitting. In the upper floor bathrooms, under crumbling paint, aspiring artists drew elaborate pencil pictures, and in electrical closets, A.A. Brown wrote in pencil about his inspection work.

F.W. Menke did the excavating and put in the foundation. Tenk Hardware at 512 Maine did the electrical wiring and installed fixtures. Galvanized iron cornices and ornamental work was done by W.F. Burghofer of 510 Jersey. George Starman at 640 Maine did the painting and glazing. Buerkin and Kaempen installed the woodwork. And Joseph Eiff did the plastering and decorating.

The elevator on the east end was constructed by Central Iron Works of Quincy and was originally capable of lifting 2,000 pounds at 200 feet per minute.

In November 1899 there was an elevator accident that badly frightened employee Thomas D. Lyons. He was in the car when it abruptly traveled from the fifth floor down to a point two feet above the third floor where its iron cage twisted and jammed, allowing the janitor to crawl free. It was reported that Thomas "turned nearly white and beads of perspiration stood out on his face like dew on a rose petal." The elevator inspector said that the cable had slipped from the cable drum. Elevator mechanics, called in to fix the problem, disagreed, saying that it had not fallen, it simply had "failed to stop."

In any event, the elevator was boarded up by drywall four or more decades ago. Recently the drywall was removed from the original entrance area to reveal a Hollister Whitney carriage car installed in 1920.

The first corner storeroom belonged to H. Schroeder, "the oldest and best known druggist in the city," wrote the Quincy Daily Journal. Dr. H.W. Wellman had his dentist's office on the first floor, and Le Grand Haskin, known as an expert optician and maker of watches, had the middle rooms on the first floor. In the early years the building was home to numerous physicians, including a Dr. Glower on the third floor. One of Quincy's most famous and influential citizens, Lorenzo Bull, had an office in the building in his last years.

In 1905, Mercantile Bank bought the building and opened on the main floor. The original bank vault in the basement, made by the now defunct Mosler Safe Company, is still being used by the Adams County Genealogical Society. The basement itself was fully floored and plastered. The original stairs that led down from the main floor and allowed tellers to bring large deposits into the safe are still visible in the basement, as are some of the old bank teller grates. Another vault was constructed on the east end of the main floor and is still visible today.

The building holds many clues to past occupants. On the second floor was Fisher Jewelers, and the last tenant was Sunshine Cable Radio, now known as WGCA and housed in the nearby Maine Center. The radio control room is still there and the signs remain in the windows.

On the fourth and fifth floors there are windows with the names of the prior occupants, businesses like the D.D. Donald Co. Merchandising Brokers, J.B. Murphy Real Estate & Appraisals, and the W.G. Houston Company. Mr. Houston had an office on the west end of the fourth floor and his name is still on the window.

A prominent tenant from the early years was the Wilson and Schmiedeskamp law firm. George Wilson and Henry Schmiedeskamp started the firm in 1914 and were on the fourth floor originally, went to the second floor in 1928 and then back up to the fourth floor. The Schmiedeskamp brothers, Henry and Carl, split in 1948, and there were other law offices on the fifth floor. By 1962 all the firms were gone. On the west end on the fifth floor is a safe, with the faint letters spelling the name of the law firm imprinted above the heavy wooden doors.

The views of the city are spectacular from the upper floors, and the roof offers incredible displays of the Mississippi River, and the lock and dam. On clear nights the lights of Palmyra and Hannibal, Mo., can be seen.

Rodney Hart is a former sports editor, columnist and reporter for The Quincy Herald-Whig, and currently contributes weekly articles and blogs to the newspaper. Rodney and his wife, Sheryl, are the new owners of the Dodd Building, where their business, Second String Music, is located.

Sources:

"Death of Mrs. H. Dodd," The Quincy Morning Whig, 23 Aug. 1899

"Did it Fall or Fail to Stop?" The Quincy Daily Journal, 4 Nov. 1899

"Mrs. Hattie Dodd," The Quincy Daily Journal, 22 Aug, 1899

"Quincy's Fine New Building," Quincy Daily Journal, 18 Nov. 1897

"The City," Quincy Daily Herald, 30 Jan. 1878

"Very Old Landmark," The Quincy Morning Whig, 30 Apr. 1897