Lessons learned from Tremont Hotel fire

The fire that destroyed the Newcomb Hotel on Sept. 6, 2013, was one of Quincy's worst disasters, though far from the only one.

More than a century ago on June 22, 1904, a fire swept through the Tremont Hotel located on Hampshire between Fifth and Sixth streets, the present day site of WGEM broadcast studios and the New Tremont Hotel. The conflagration caused more than $40,000 in damages and tragically, the lives of two Quincy public school teachers.

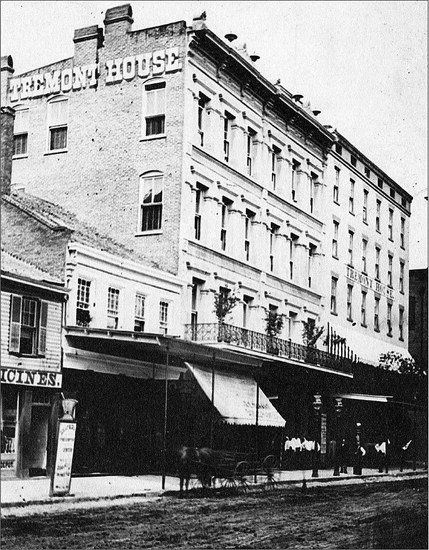

June 22, 1904, fell on a Wednesday. It was a typically warm June day. The fire began later that afternoon at the Tremont House. That edifice was completed in 1877 and two years later President Rutherford B. Hayes spoke from its balcony. Sometime short after 5 p.m. a shout of "Fire" came from the hotel. The flames began in the linen room on the 3rd floor and soon the ten-story building was engulfed in flames. The hotel's desk clerk, Homer H. Cleveland, hit the alarm bell, as did others in the area. However, a mistake was made, as the fire department believed the fire was at Fifth and Jersey. The delay proved costly, as the flames spread to the upper levels of the hotel.

Living in the hotel at the time were two sisters, Elizabeth Welch and Mary Welch. Elizabeth Welch was the principal of Jefferson Elementary School, while her sister Mary was the principal at Jackson School. The sisters were in their apartment on the fourth floor when they heard the cries. It was not their first experience with a blaze. Almost incredibly, Mary and Elizabeth had survived three previous fires, including two at the Tremont. But this time the fates were against them. Instead of running for the stairs, they decided to wait for the fire officials and the ladders, a decision that proved deadly. As they waited, the fire continued to spread, trapping them in their room. Elizabeth died that day, while the fire department was able to manage a heroic rescue of an unconscious Mary. Unfortunately, Mary had suffered severe burns on her face, chest, and arms, and had smoke inhalation. She died the following day. Five others were injured in the fire, though none of them fatally.

The cause of the fire was never determined. As the fires died out, public opinion turned against the Quincy Fire Department. In a biting editorial published two days after the tragedy, The Quincy Daily Journal blasted the department for its apparent faulty response. The paper wrote: "All along the line there is loud and strong complaint over the mismanagement of the fire department at the Tremont house fire. This, on the part of visitors to the city as well as on the part of our own citizens. The condemnation of the management of the department at that fire is well nigh unanimous." The paper took pains to draw a distinction between the "private men" of the department and the "city administration and the fire chief." The former consisted of brave men doing the best they could, while the latter were incompetent and venal. The fire, and the response, demonstrated, according to the paper, a need for comprehensive change, and when that reorganization came, "we shall see how weak and inefficient the department is as it is presently organized and officered." And that department was inefficient because of one man -- Mayor John A. Steinbach. The Daily Journal pulled no punches, accusing Steinbach of using his "personal hobby" of the city waterworks department instead of aiding other vital services. "Streets, sewers, lights, police department, the fire department, public improvements, park improvements -- all these have been made to suffer because John A. Steinbach has insisted in putting money to buy a water works plant."

Within a few days of the fire, a coroner's jury was convened to investigate the fire and the deaths of the Welch sisters. After hearing from over a dozen witnesses, the jury came back with its verdict on June 30. The jury concluded the fire was caused by the "carelessness of the part of electrical employees." The jury also placed some of the onus on the city's fire department, claiming the lack of immediate response and the faulty alarm system contributed to the tragedy. The jury recommended that a new alarm system be installed. Just one day after the Tremont fire, the alarm system proved faulty again. A small chimney fire broke out on Hampshire, and though no lives were lost, the lack of a quick response gave impetus to install a better and improved fire alarm system.

The tragic loss of life led to the city of Quincy implementing major changes in its fire code. Fire escapes were required of most buildings, including the public schools. A new alarm system was installed. Later on, new codes required that sprinkler systems be installed in commercial buildings. Although fires remain a part of life, the lesson of the Tremont Hotel fire ultimately helped make Quincy a safer city.

Justin P. Coffey is associate professor of history at Quincy University , where he specializes in recent American history and is the author of numerous articles. He also serves as president of the Historical Society of Quincy and Adams County.

Sources:

Carl and Shirley Landrum, eds. Quincy, Illinois, Ibid.

The Quincy Daily Whig, June 23, 1904, 1.

The Quincy Daily Journal, June 23, 1904, 5.

The Quincy Daily Journal, June 24, 1904, 4.

The Quincy Daily Whig, July 1, 1904, 5.

The Quincy Daily Whig, June 24, 1904, 1.