How Lucile Langhanke of Quincy Became Mary Astor of the Silver Screen

Born in Blessing Hospital in Quincy, on May 3, 1906, Lucile Langhanke was the only child of Otto Langhanke and Helen Vasconcells Langhanke. Emigrating from Germany in 1890, Otto eventually lived with his mother in Topeka, Kansas, where he worked as a window trimmer for Crosby Brothers. On August 3, 1904, Otto married fellow Crosby Brothers employee Helen Vasconcells in Kansas. They moved to Quincy in 1904 where Otto had a job at the Stern Clothing Company and taught German at Gem City Business College. In 1906 he began teaching at Quincy High School. After a fistfight in the school halls with another teacher, the high school fired him in 1912 but reinstated him in 1916. Other occupations included decorating store display windows in 1914 at Stern and running his own poultry farm. Born in Jacksonville, Illinois, Helen was a drama teacher who wanted to be an actress. She also taught German in 1917 at the Quincy College of Music and Art, as had Otto from 1905.

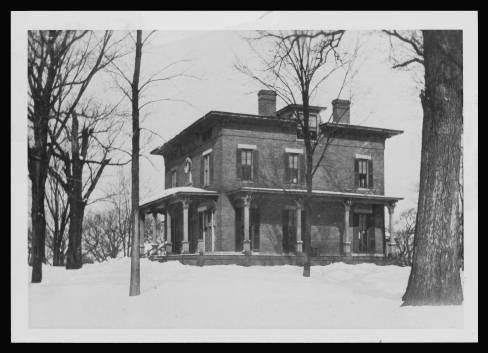

After Lucile was born in 1906, her family lived for a few years in an apartment over the Boston Store, a dry goods store, at 725 1-3 Hampshire. From at least 1910 until 1913, their address was 1837 Broadway. In 1913, they rented a 12-room Victorian mansion on 2335 N. Twelfth Street, outside of the Quincy city limits, and just north of the Illinois Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Home, now known as the Illinois Veterans Home at Quincy. Lucile loved being by herself on this eight-acre farm. She attended Highland School, a two-room schoolhouse. When Otto got his teaching job back, the family left the farm for 1244 Kentucky Street in Quincy.

The author of a German-language textbook and a teacher’s manual, Otto was a faculty member at Quincy High School for the 1917–1918 school year. Because of anti-German feeling he again lost his teaching job. This prompted the Langhankes’ move to Chicago. There they resided in an apartment at 1120 East 47th Street, and Lucile miserably attended public school. After Helen became a teacher of literature and drama at the Kenwood–Loring School for Girls, at 4600 Ellis Avenue, Lucile was admitted as a tuition-free pupil. She loved the school and enjoyed her mother’s teaching. Lucile graduated in 1919.

Lucile won some attention by entering beauty contests sponsored by Motion Picture magazine. On the strength of this thin reed, the Langhankes moved to New York, where Otto sought to promote Lucile as a fledgling actress. The photographer Charles Albin created some hauntingly beautiful photographs of her. They finally caught the attention of movie executives which got her parts in silent films, and eventually won her contracts as the newly renamed “Mary Astor.” In 1920, she was only 14—a very young, very intimidated child-woman.

For many years, Otto was Astor’s business manager and controlled/spent her income. More than that, Otto and Helen controlled their daughter’s every move. She had no studies, no boyfriends, no girl confidantes. Her parents opened her mail, read any letters she wrote, did not allow her to venture out alone, not even to the mailbox, and discouraged any friendships outside the family.

Besides controlling her money and her every waking moment, Otto berated her as a stupid, bad daughter. According to her book, A Life on Film . “I was a constant failure. He indicated his disappointment with windy sighs and shakes of the head.” “He was going to be a rich man if it killed me….I was a real disappointment, that I could see.” Helen’s attitude was no more accepting. Inscribing her diary with hostile words, Helen left for her daughter to read after Helen’s death a journal filled with hate.

In My Story: An Autobiography , published in 1959, Mary Astor was candid about her four troubled marriages and recurrent financial stress, as well as a sex scandal fueled by speculation about the real content and the forged pages of her private diary, left deep wounds. Her lifelong struggle with alcohol was eased at times by her religious faith, which encouraged self-awareness, self-acceptance, freedom from “the confining mass of self-centered thinking—infantile, emotional, ineffective solutions to problems that had bound me deeper and deeper in loneliness and misery.” Weak in many ways, she yet had a strong core: “I was fortunate enough to have an inherent vitality; the deepest need, survival, was very strong.” Astor’s courageous description in her memoirs of her plight demonstrated great strength underlying manifest weakness.

Self-acceptance demanded the rejection of “Mary Astor,” the imposed identity and enforced ambition. Writing as “Rusty,” in a late-life letter to her only childhood friend, Marian Fisher Kesler of Quincy, she confided, “I have been going through a battle royal with the devils that seem to pursue me. . . .when I first turned my back completely on ‘Mary Astor’ ‘She’ was furious! And I fled and kept running. And ran into ‘her’ everywhere I went….let’s let ‘Mary Astor’ belong to history. Let her have her Oscars and her glory—and let ‘her’ die . Damn her. She is no part of my soul…. So have faith in your friend and pray for Rusty.”

The question remains, if Mary Astor was one of the biggest female stars of the silent era, why wasn’t she doing more leading roles in sound films? She seemed to suffer from depression, as well as alcohol abuse, and she had tried suicide. Her memoirs describe financial exploitation and emotional abuse. All of this creates a picture of self-destructiveness. But this is far from the whole story, which is one of courage and recovery. Today she is mostly remembered for her roles in The Maltese Falcon and Meet Me in St. Louis . Her best acting Oscar was won in 1941 for The Great Lie.

Sources

1900 and 1910 United States census.

Astor, Mary. A Life on Film . New York: Delacorte Press, 1971.

Astor, Mary. My Story: An Autobiography. Garden City, NY: Doubleday & Company, 1959, pp. 29-30.

Document 2B5, Mary Astor Papers: Marian Kesler Collection. Quincy Public Library, Quincy, IL.

Landrum, Carl. “Lucile Langhanke Was Mary Astor—Quincy’s Famous Movie Star,” Quincy Herald-Whig , 10 December 2000.

Landrum Carl and Shirley Landrum. Quincy, Illinois. Charleston, SC: Arcadia, 1999, p. 40.

Mary Astor, Letter 2A45-2, 2A45-3, and 2A45-4 to Marian Kesler, undated [between 1972 and 1974], Mary Astor

Papers: Marian Kesler Collection. Quincy Public Library: Quincy, IL.

New York, Passenger and Crew Lists (including Castle Garden and Ellis Island), 1820-1957.

SeeQuincy.com, Quincy Off the Record. n.d. pp. 2, 4.

Topeka, Kansas, City Directory, 1902.