The Rev. Dr. David Nelson Arrives in Quincy

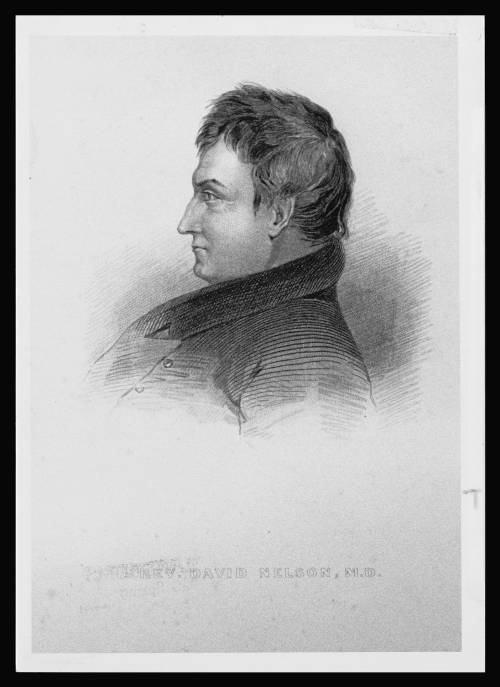

Tall grass growing along the Mississippi River hid the Rev. Dr. David Nelson from pro-slavers looking for him on Sunday, May 22, 1836. Public opinion had been seething against Nelson, the founder and president of Marion College at Palmyra, Missouri. Nelson was an agent of the American Anti-Slavery Society for Missouri and one of the society’s vice presidents.

The people of Palmyra uneasily tolerated him. A few days before he was chased out of Missouri under a death threat, Nelson had agreed to leave. The college had turned against him. “The faculty . . . utterly condemn any interference with rights guaranteed by the State of Missouri to the owners of slaves.” Nelson decided to move to Quincy.

David Nelson, a medical doctor, volunteered as a surgeon in a Kentucky regiment during the War of 1812 and was with General Andrew Jackson in his invasion of Florida in 1818. Jaded by what he saw and experienced in war; Nelson shed his religion.

After military service he returned home to Jonesboro, Tennessee, and established a medical practice that generated income of $3,000 a year. The money proved to be unsatisfying as did his lack of religious affiliation.

Nelson joined the Jonesboro Presbyterian Church, “deploring his long rejection of the Saviour he now delighted to honor and resolving to redeem the time by the unreserved consecration of all his powers to Him.” He attended Centre College at Danville, Kentucky, and helped start the Danville Theological Seminary. At college he developed an anti-slavery spirit, freed his slaves and sent them to Liberia. His form of abolition favored the colonization of emancipated slaves.

The Rev. Nelson was imposing at six feet tall and 250 pounds. As a preacher whose emotions during a sermon could move him to tears, he was said to have few equals in eloquence and effusion in the spirit of Christ. In January 1832, he preached in St. Louis’s First Presbyterian church to hundreds of men and women who felt his “surgeon’s knife probe deeply” into their conviction to sin.

Among the attendees was Elijah Lovejoy, who had resisted Nelson’s “knife” but found himself converted by the end of two weeks of revival. Lovejoy’s conversion was so complete that he became a Presbyterian minister determined to end the sin of slavery. His firebrand anti-slavery Alton Observer cost him diminishing support in Alton. Friends in Quincy repeatedly urged him to move his press there. Lovejoy declined. In November 1837 he was martyred by a pro-slavery mob in Alton. Nelson sought to multiply the spirit that had moved infidels like him and Lovejoy. It was this spirit that “led him to lay the foundation of Marion College in Missouri.”

He chose to establish his college at Green’s Landing on the Mississippi, renamed Marion City, which was approximately eight miles north of Palmyra. Col. William Muldrow had invested huge sums in land there. His plan was to locate a rail terminus to the Pacific. The plan lured money and easterners to Marion County, whose ideas about slavery were unpopular. Muldrow expected Marion City to replace Quincy as the commercial center on the Upper Mississippi. The river intervened. In 1835 it flooded over Marion City and dissolved Muldrow’s plan.

It was Muldrow who ran Nelson afoul of his neighbors that Sunday in May of 1836. Against his better judgment, Nelson consented after a camp meeting that day to read an appeal by Col. Muldrow, a college founder and now a board member, for contributions to colonize free blacks in Africa.

For several listeners, the request represented the final insult against their institution. It demonstrated to them that Marion County had become “. . .a selected theatre of action for the dissemination of the principles, and the accomplishment of the objectives, which form the band of union of anti-slavery associations of the east.”

Many owned small numbers of slaves in Marion County. Fighting—some called it rioting—erupted, and Dr. John Bosely, a slave owner who had stirred it, was stabbed. Nelson was blamed for the altercation. His frantic wife persuaded him to flee for Quincy. For the next three days he sneaked wet and muddied along the river bank.

Quincy abolitionists John Burns and George Westgate found Nelson, who by then had traversed the bottoms of the South Fabius River to a point across from Quincy. Nelson’s rescuers had brought dried codfish and crackers for him to eat. It was unusual but welcome food for the fugitive. He told his deliverers they would make a Yankee of him and that he “may as well begin on crackers and codfish.”

Nelson spent the night in Rufus Brown’s log cabin hotel, on the southeast corner of Fourth and Maine Streets in Quincy. His sleep was disturbed the next morning by several men. Word had circulated that Nelson had stabbed Dr. Bosely. When it became clear that Nelson planned to move to his family and his troublesome college to Quincy, the “self-constituted committee of citizens” demanded he return to Missouri. “The men of this committee . . . were not bad men, but simply Democrats,” wrote Henry Asbury, a lawyer and local historian, about the altercation.

Democrats or not, John Wood and thirty armed men showed up to confront the mob at Brown’s hotel. If they were going to take Nelson, Wood warned, “they would have to take him over their dead bodies.” Wood’s determination broke up the crowd. It was the first time since 1823, when he fought a pro-slavery legislature’s attempt to make Illinois a slave state, that Wood once again put his own sensibilities about slavery on the record.

Two weeks after Nelson’s arrival, a notice was placed in the Illinois Bounty Land Register , Quincy’s first newspaper, “for a ‘county meeting’ in the public square of all citizens of Adams County friendly to peace and good order and opposed to the introduction of Abolition Societies and opposed to the discussion of the subject in the pulpit.” The struggle over slavery had crossed the river.

Sources:

Asbury, Henry, Reminiscences of Quincy . Quincy, Illinois: D. Wilcox & Sons, Printers, 1882.

Blackwood, James, “Quincyans and the Crusade Against Slavery: The First Two Decades, 1824-1844. Macomb, Illinois: Master’s

Thesis, Western Illinois University, Macomb, Illinois, 1972.

Deters, Ruth, The Underground Railroad Ran Through My House! Quincy, Illinois: Eleven Oaks Publishing, 2008.

Dillon, Merton L., Elijah P. Lovejoy, Abolitionist Editor. Urbana, Illinois: University of Illinois Press, 1961.

Lovejoy, Elijah P., Memoir of the Rev. Elijah P. Lovejoy. Freeport, New York: Books for Libraries Press, 1970.

Nelson, The Rev. David, M.D., The Cause and Cure of Infidelity. New York: American Tract Society, 1841.

Richardson, William A. Jr., “Dr. David Nelson and His Times,” Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society, Vol. XIII, Springfield, Illinois: Illinois State Historical Society, 1921.

Simon, Paul, Freedom’s Champion, Elijah Lovejoy. Carbondale, Illinois: Southern Illinois University Press, 1994.

Tillson, Col. John Jr., History of Quincy, in William H. Collins and Cicero F. Perry, Past and Present of the City of Quincy and Adams County, Illinois. Chicago: S.J. Clarke Publishing Co., 1905.