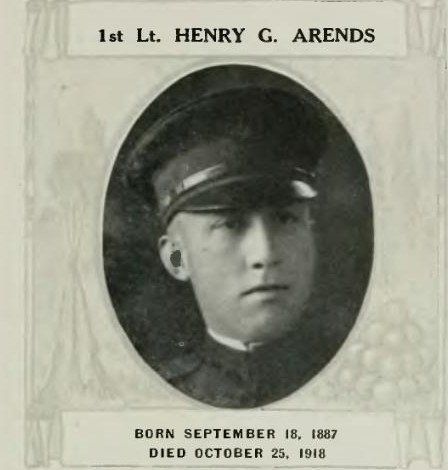

Lieutenant Henry G. Arends Rests in France

A week to the day after the armistice ending the First World War took effect; the Arends family received a telegram from the war department stating that their son, First Lieutenant Henry G. Arends, had died on October 25, 1918. The Quincy Daily Journal reported that the family had been notified on November 8 by “the matron of an English hospital that their son had been critically wounded in action . . . and though everything possible was being done for him, little hope for his recovery was held.” The Journal wrote that “the parents . . . have as the days passed taken continued hope, so the news of his death comes as a shock to them.”

Gerhard G. Arends, Sr. left Germany in 1846. Three weeks after setting foot in the United States, he volunteered for the Mexican War. On returning, he settled in St. Louis, but in 1849, he and his new bride moved north to Quincy. A carpenter by trade, Arends quickly found employment and eventually opened his own shop. His son and only child, Gerhard, Jr., was born in 1854. He would become the cashier of the Quincy National Bank. Henry G. Arends, Gerhard, Jr.’s only son, was born in Quincy on September 18, 1887. He graduated from Quincy High School in 1906, the University of Missouri in 1910, and the University of Missouri law school in 1912.

On the United States’ entry into the Great War, Henry Arends quit his Chicago law practice and enlisted in the army. He was in Fort Sheridan’s first officer’s training class. Upon graduation and receipt of his second lieutenant’s commission, Henry was sent to France.

Landing in France on January 11, he was immediately assigned to the British for further training. When the 30th Division arrived in late May, Arends was an instructor in grenade throwing and poison gases. The unit was made up of National Guard troops from the Carolinas and Tennessee and was called the “Old Hickory Division” after Andrew Jackson, who had lived in all three states. Now a first lieutenant, Arends became an infantry officer in division’s 119th regiment.

From the moment General John Pershing was put in command of the American Expeditionary Force, he resisted efforts to amalgamate American troops into the British and French armies. Despite Pershing’s efforts, an agreement was reached between the respective governments whereby the British would transport some American divisions to France. They would then train, feed, and arm these troops. As a result, two American divisions were permanently loaned to the British to use as they saw fit. The 30th was one of those divisions.

On July 2, 1918, the 30th entered the frontline trenches at Ypres, Belgium. July 12th’s Daily Journal reported that Lt. Arends had “been up to the firing line with his command.” The men spent the next two months in combat as they pushed the Germans back, receiving a short-lived rest on September 1.

From August 13th’s Daily Journal: “Lieutenant Henry Arends writes that he is in the first line trenches for the third time.”

The October 25th edition of the Daily Whig printed part of a letter from Lt. Arends to his parents. “Just returned from a three weeks tour in the line again. While we were there we captured a village and went twice ‘over the top,’ so we feel that we have done pretty well. We are very tired and very much in need of rest. I am feeling fine, but still am in too advanced a position to have a picture taken. All the towns here are shot up and I have a bunch of souvenirs here which I should like to send you if I could. We are pushing the Boche back into Germany and over the Hindenburg line. That’s doing well, don’t you think?”

Lt. Arends last letter was dated October 15. He wrote that he expected to return to the front the next day. Having had a brief rest, the Old Hickories were back on the offensive beginning October 17. In three days of continuous heavy fighting, the 30th advanced nearly five miles. All the while German artillery fire and mustard gas rained down on the attackers. The night of the 19th and 20th the regiment was relieved and sent to the rear for rest. Unbeknownst at the time, the division’s war was over as they saw no more fighting.

During that last day of combat, Lt. Henry Arends received a severe head wound. He “was conveyed to General Hospital No. 8 of the British Expeditionary Forces” where he died on October 25.

His remains are interred in the Somme American Cemetery in France which was established in October 1918. The area saw heavy fighting, and it is a fitting final resting place for 1,844 United States soldiers---men who never came back. These men served in the American II Corps and were attached to the British Fourth Army. Most were killed in the assault on the Hindenburg line.

On April 8, 1923, the Historical Society unveiled a bronzed tablet bearing the names of the 81 men from Adams County who gave their lives during the First World War. Nineteen, like Lt. Arends, were killed in action or died of wounds. While disease or accidents claimed 62 men with most succumbing to the Spanish influenza epidemic.

The speaker that afternoon, the Rev. M. Edward Fawcett, concluded by saying: “. . . I look at the tablet which patriotism and love as well as duty has designed, and it seems to assure me that the heart of America is more sound than . . . events would seem to indicate. Whatever our wanderings we have not forgotten, and we will not . . . fail to honor those who gave their all. . . .”

Sources

Collins, William H. and Perry Cicero F. Past and Present of the City of Quincy and Adams County, Illinois. Chicago, Illinois: The S. J. Clarke Publishing Co., 1905.

Conway, Coleman Berkley. History119th Infantry60th Brigade, 30th Division, U.S.A. Operations in Belgium and France, 1917-1919. Wilmington, North Carolina, 1920.

Genosky, O.F.M., Rev. Landry, ed. Peoples History of Quincy and Adams County, Illinois. Jost & Keifer Printing Co.: Quincy, Illinois, 1973

History and Achievements of the Fort Sheridan Training Camps. The Fort Sheridan Association, 1920.

Quincy Daily Herald, May 15, 1899; October 25, 1918; November 8, 19, & 20, 1918; December 16, 1921; and April 10, 1923.

Quincy Daily Journal, July 19, 1918; August 13, 1918; November 9 & 19, 1918; and April 9, 1923.

Quincy Daily Whig, October 25, 1918 and November 9, 1918.

Stallings, Laurence. The Doughboys: The Story of the AEF, 1917-1918. Harper & Row, Publishers, 1963.

Wilcox, David, ed. Quincy and Adams County History and Representative Men. Chicago and New York: The Lewis Publishing Company, 1919.

“World War I & North Carolina: 30th Division, 119th Infantry.” The Cromulent Manifesto. Online April 16, 2018.

Yockelson, Mitchell. “Borrowed Soldiers: The American 27th and 30th Divisions and British Army on the Ypres Front, August-September 1918.” The Army History Center online July 20, 2016.