Lincoln and Quincy's most historical event

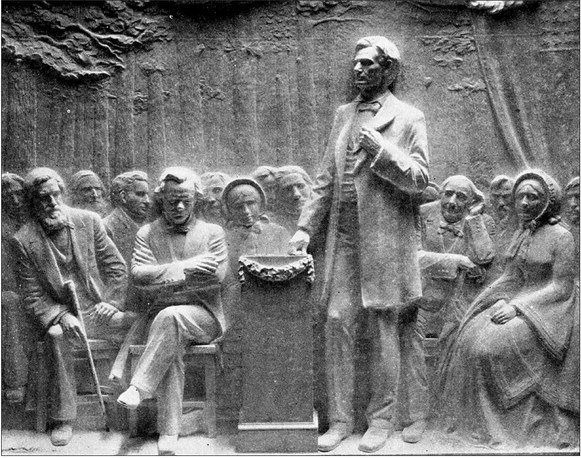

The city of Quincy has a rare political distinction. By hosting the sixth of the seven Lincoln-Douglas debates in 1858, the community can celebrate itself as instrumental in Abraham Lincoln becoming the Republican Party’s successful candidate for president in 1860.

Compelling evidence exists that the sixth debate stands apart from the five previous debates in suggesting that Lincoln would be the appropriate candidate of his party for the highest office in the land. Significant documentation was uncovered by the Research Committee of Quincy’s Lincoln Bicentennial Commission. Local research revealed facets of the sixth debate that other researchers have overlooked or ignored. This is despite an extraordinary volume of works on the debates. This research on the sixth debate has led to the conclusion that the Quincy debate was the “turning point” in Lincoln’s political career that culminated in his becoming the nation’s 16th president.

The immense significance of the sixth debate has not entered the Lincoln or debate literature. To sustain the story the research team of the Lincoln-Douglas Interpretive Center has created an exhibit in the Center at 128 N. Fifth to present its evidence and make accessible its unique interpretation of the Quincy debate.

The seven Lincoln-Douglas debates of 1858 constituted the centerpiece of the Illinois senatorial campaign. When reading through the debates one is struck by the nearly endless repetition. This arises from the fact the debaters could not assume that the audience knew much, if anything, about their previous debates. Thus the reader looks for differences that may appear in any debate.

For example, after a disappointing first debate at Ottawa, Lincoln came armed with a series of questions designed to trip Sen. Stephen Douglas at Freeport. The “Little Giant” was ready and articulated what became known as the “Freeport Doctrine.” Douglas quickly turned the tables and made charges that Lincoln had to address and the tone for the debates was established; Douglas on the offense, and Lincoln defending himself and his party. The sub-theme of Douglas’ charges related to race with the suggestion that Lincoln was an abolitionist and for racial equality. Lincoln spent an inordinate amount of his time defending his moderate anti-slavery positions.

Underscoring the importance of the debates was the eminence of Douglas. He was seeking a third term and he was universally recognized as the most powerful and influential member of congress. He exceeded in stature and influence the rather nondescript presidents of the 1850s (Fillmore, Pierce, and Buchanan). By sharing the podium with Douglas, Lincoln was aware he was guaranteed a wide audience. He acknowledged that fact in the Quincy debate that their audience was not simply the assembly in Quincy’s Washington Square. Lincoln realized that his own strongly held views on the key debate issues, slavery and slave expansion, would be given an extraordinary exposure.

The first debate was held in Ottawa on Aug. 21, 1858. Subsequent debates followed in six additional congressional districts. The final three debates came in October at Galesburg, Quincy, and Alton. Throughout the debates the fiery Douglas possessed a great capacity for keeping Lincoln on the defensive by various charges, real and imagined. A prime example would be that Douglas charged that Lincoln tailored his message to suit the audience, aggressively anti-slave in the north of the state and with a muted concern for black equality in the south. Lincoln repeatedly attempted to answer Douglas’s taunting charges.

Lincoln’s demeanor changed after a less-than-satisfactory showing at Galesburg, a city that seemed to be prime Republican territory. The catalyst for the change came from a trip to Burlington, Iowa, after Galesburg, where Lincoln spoke to a large, enthusiastic crowd. Obviously there was no Douglas to bait and level sarcasms. Lincoln’s host at Burlington was Iowa’s governor, James W. Grimes, a Burlington resident.

Grimes discussed Lincoln’s debate performances and is quoted as sharing this advice, “I insisted that he suffered Mr. Douglas to put him too much on the defensive, — that he should assume the aggressive and attack his adversary in turn — that it was useless to defend himself against Mr. Douglas’ charges, for as one could be refuted another would be trumped up.” Lincoln asked for writing supplies, went to his room, and spent about an hour and a half taking notes. Gov. Grimes wrote that he was satisfied that these notes provided vital new directions coloring events at Quincy the following week. The advice given by Grimes has been overlooked and has not been used in understanding the new stance that Lincoln took on in the last half hour of the debate.

Illustrating a new approach and vigor, Lincoln expanded on previous statements about slavery and slave expansion. Underlying all was Douglas’ commitment to “popular sovereignty,” which conferred upon a territory the right to choose whether to be free or slave. Lincoln and Republicans accepted the fact of the existence of slave states, but decreed that slavery should be kept from expanding, resulting in slavery eventually withering and dying. Before the debates even began, Lincoln had dramatized his position by quoting scripture, “that a house divided against itself cannot stand. That it ultimately must become all one or the other.”

In his response, Douglas cajoled Lincoln for this statement, while Lincoln at Quincy stressed in strong terms that slavery was a moral evil and upbraided Douglas for “never having said slavery is either right or wrong.” Further dramatizing his differences with Douglas, Lincoln asserted, “I wish to return to Judge Douglas my profound thanks for his public annunciation here today…that his system of policy (popular sovereignty) in regard to slavery contemplates that it will last forever.” Grimes’ advice and suggestions were being dramatically implemented.

Another apparent example of Grimes’ influence came when Lincoln clarified his position on the Declaration of Independence. Douglas had been badgering Lincoln repeatedly about the Declaration that Douglas said applied to only whites of European origin. Historian Vernon Burton showed that Lincoln made his position clear at Quincy with this quote. “There is no reason in the world why the negro is not entitled to all the rights enumerated in the Declaration of Independence – the right of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. Lincoln went on to declare: “In the right to eat the bread without the leave of anybody else, which his own hand earns, he is my equal, and the equal of Judge Douglas, and the equal of every other man.”

At Quincy, Lincoln powerfully exploited his differences with Douglas and in the process positioned himself as a strong, but moderate leader of the Republican party. He eschewed abolitionism, which was anathema to most Republicans. Because of the widespread dissemination of the debates in national newspapers, an otherwise merely a state candidate could and did become a national figure. This was thanks to Douglas, and the adage “no Douglas, no Lincoln” possesses a genuine relevance.

Representing this premise, an Ohio newsman, David Locke, attended the Quincy debate and also was able to interview Lincoln. Why Locke chose Quincy as the one debate to attend is a mystery, but because Lincoln had been so influenced by Governor Grimes’ advice it was especially fortunate.

Locke was so impressed with Lincoln that barely two weeks later; Locke’s Sandusky Ohio Commercial Register published a headline, “Lincoln for President.”

The article then described an enthusiastic local meeting promoting Lincoln as the Republican candidate for the highest office in the land.

Almost immediate post-debate endorsements came from other newspapers in both Illinois and Ohio. So, despite failing to be elected senator, Lincoln’s moderate message had propelled him into being seen as presidential potential.

Endorsements came from other newspapers in both Illinois and Ohio. In 1859 and 1860, Lincoln became a popular speaker, accepting invitations from Iowa, Kansas, Indiana, Ohio, and Wisconsin to repeat his moderate anti-slavery position in those states. Ultimately, Lincoln gave a powerful speech in New York City at Cooper Union on Feb. 27.

Historian Harold Holzer describes it as “The Speech That Made Abraham Lincoln President.” It had all started with the Lincoln-Douglas debates in seven Illinois cities in 1858 and specifically at the sixth debate at Quincy on October 13, 1858.

In historical annals, the concept of “turning points” is a frequently used device. Sometimes the concept is valid, and at times it is a shortcut to gain attention. The Research Committee of the Lincoln Douglas Interpretive Center after careful study of the debates came to the conclusion that the overlooked intervention of Grimes and the fortunate circumstance of newsman David Locke attending the Quincy debate produced such a dramatic effect on Lincoln’s political fortunes that it warranted being seen as the “turning point” for Lincoln’s political career.

This breakthrough evidence impelled the committee to put the story together in detail in an eight-sided kiosk in the Interpretive Center to make known the significance of Quincy to Lincoln’s rise to power.

Professor emeritus David Costigan held the position of the Aaron M. Pembleton endowed chair of history at Quincy University.