Log book tells tales of debt from the early 1900s

Today it's possible to make a purchase by waving your smartphone at the charge machine. It was not always so easy. Long before the conveniences like credit cards, time payments or installment loans, people still needed to borrow money, stretch payments over time or obtain money to sow next year's farm crops.

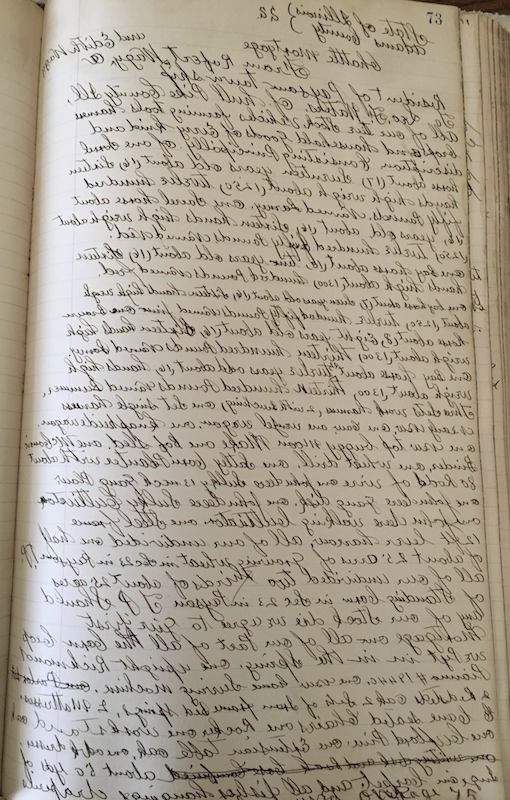

The log book of the Adams County Justice of the Peace in Payson illustrates how this was done through its many records of chattel mortgages. Chattel is something that someone owns that is neither land nor a building. Sometimes chattel is defined as an article of movable personal property. In 1903-20, the years covered by this log, chattel usually meant livestock, farm equipment and household goods as well as a variety of other, sometimes odd, things.

Property listed as security for these loans gives a detailed picture of the times. But a mortgage was a cumbersome way to structure payments. In 1913 Henry Madison, publisher of the Plainville Messenger, bought from a Chicago company, A.F. Warner, a new cylinder-drum printing press for his business. Madison signed 12 notes for $10 each, payable monthly and due one to 12 months from the date of the mortgage; then 12 more notes at $15 due monthly after that.

The log book lists only one automobile, a Chalmers 40 horsepower auto No. 6511. It was pledged against a note of $500 at 6 percent interest for one year. This mortgage was executed June 14, 1913. There are a few "traction engines" listed among the farm property, and among the many pieces of horse-drawn equipment are a few made by manufacturers with names like McCormick or John Deere.

Reasons for loans are not given, but the collateral varies widely. In December 1910, the local barber needed a loan of $50 for 90 days and pledged "Two Barber chairs; One Wash stand and Three Barber Bottles" as chattel.

If payment was missed, the lender could repossess a team or wagon or even household goods down to the carpets.

One mortgage from 1905 to lender Leo Waters seems to list every movable item that Edith and Robert Wagy owned. It begins with the words that they are pledging "All of our live stock vehicles farming tools harness and household goods of every kind and description whether mentioned in this mortgage or not…" then it lists in detail everything from a horse named Barney to a Knapheide wagon, a moon-top buggy, a bobsled, a McCormick binder, a Satley corn planter, plows, cultivators, a harrow, a Richmond piano No. 19440, a home sewing machine, two bedsteads of oak, one iron frame bed, mattresses, a rocker, a washstand, a cupboard, an extension table, 50 yards of "morane" carpet, dishes, hanging draperies and shades, bric-a-brac tables and cooking utensils. It goes on to encumber the crops sown in the field, not yet harvested. The total of this mortgage was $1,047.50, due in a year.

If a lender took something wrongly, perhaps in response to a missed payment, the answer was an "Action of Replevin," in which the justice of the peace ordered an item returned. On Sept. 29, 1909, Robert Wagy filed such an action against his mortgage holder, Leo F. Waters, saying that Waters "did take and unlawfully detain one German heater stove, two joints stove pipe and one pipe elbow."

Waters' name appeared in the book over 40 times as a source of funds, often renewing a loan with a slightly lower or higher amount, depending on how much the borrower had managed to pay, or if missed payments were rolled into a new loan.

Livestock was included in the chattel because most people farmed with valuable horse and mule teams. The horses were described by age, color, weight and often by name. The list of horses' names sound simple to today's ears: Ned and Fred, Bill and Jim, Judge and Dan, Mollie and Bert, with an occasional Prince or Queen or Daisy. Some cows were named: Betty, Boss, Baby and Pet; but most were not. Nor were the hogs, sheep or other livestock listed except by age and weight.

This well-worn book details other incidents in the Payson area at the turn of the century that sound oddly familiar: assault and battery, carrying a concealed weapon and violating a city ordinance. Some appear to be what we would call "nuisance" lawsuits. A $10 complaint over a bed quilt was settled out of court, as were many others. Some serious charges, such as the one against Willie (William) Martin for assault with a deadly weapon (a revolver) were later withdrawn by the complainant, who was charged court costs. The costs in that case totaled $4.50: $2.80 for the constables who served warrants and $1.70 for justice of the peace fees.

In a few cases, the matter was referred to a higher court or a jail sentence imposed. This occurred with a bastard case where the court found in favor of the wronged woman and sent the matter on to the state's attorney. In 1906 Ernest Crim was found guilty of carrying a concealed weapon and fined $25 or time in the county jail.

Local politics also rears its warty head. Papers found in the book include an "Action of Replevin" in which the Payson village seeks the return of his town seal and town minutes book," … the same has been taken and unlawfully detained by one Daniel Robbins and one EP Maher. …" The men are called to court and there the record ends.

Tantalizing also are the examples of mirror writing. John E. Coleman, the first justice of the peace, wrote a beautiful script upside-down and backward. In two cases an entire chattel mortgage is written in this way.

This book provides another reminder that history is made of folks just like us; and a further reminder not to throw away history illustrated by those quirky old letters, diaries and journals from the past.

Beth Lane is the author of "Lies Told Under Oath," the story of the 1912 Pfanschmidt murders near Payson. She is executive director of the Historical Society of Quincy and Adams County.

Source:

Payson Township Justice of the Peace Record Book, 1903-1920, Historical Society of Quincy and Adams County.