Mailing a letter in the early 1800s was expensive

Adams County was established by an act of the Illinois legislature on Jan. 18, 1825. Later that year the site near the cabin of John Wood was chosen as the county seat.

The Quincy post office was established on March 15, 1826, with the appointment of Henry H. Snow as the first postmaster. The mail was kept in a pine box in the cabin of John Wood, making his home the first site of the Quincy post office.

Five years after Snow was appointed postmaster, Robert Tillson became the second postmaster on May 10, 1831. He remained in the position until 1843.

Tillson went into partnership with Charles Holmes in 1828 to start a mercantile business on the north side of the public square. The next year they erected a frame building on the northwest corner of Fourth and Maine known as the Tillson-Holmes store. That building was the post office while Tillson was postmaster. The corner became known as “the old post office corner.”

We complain about the cost of postage continuing to increase. But the cost of mailing a letter in the first half of the 18th century was expensive. When the

Quincy post office was established, the basic postal rates were those established by an Act of Congress dated Feb. 1, 1816 (with a slight modification of one of the rates in 1825). These same rates continued in effect until 1845, 20 years after the establishment of the Quincy office.

In the early days the postal rates were determined by distance. For a single-sheet letter, the rates were as follows: Distances less than 30 miles: 6 cents; 30 to 80 miles: 10 cents; 80 to 150 miles: 12½ cents; 150 to 400 miles: 18¾ cents; over 400 miles: 25 cents.

If a person wanted to write to the folks back East, it would take 25 cents postage. In the 1840s most laborers were making 50 cents a day, although those working on a heavy-duty project such as the Erie

Canal might be making double that amount.

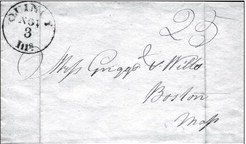

Before July 1, 1845, postage rates depended on the number of sheets of paper mailed. Therefore, the use of envelopes was rare before 1845. People wrote letters on a large sheet of paper, folded the paper, sealed it with wax and addressed

it on the outside of

the page.

The first U.S. postage stamps were not issued until 1847, and stamps were not required until 1855. The postage rate, town of origin and other markings were shown by manuscript or handstamped markings on the folded letter (or envelopes once they came into use). Because there were no stamps on these letters, they are generally referred to as “stampless covers.”

Prepayment of letter postage was not required

until 1855. Therefore, the sender could pay the postage or else send the letter unpaid with the postage to be collected from the addressee.

The folks back East were so anxious to hear from their family and friends out West that they were willing to pay the postage to hear the news. The unpaid postage also had the advantage of no one being out the money if the letter never made it to its destination.

When stamps began to be used in 1847, the postage was automatically prepaid with stamps unless it incurred additional charges, for example, if the letter had an erroneous rate resulting in postage due.

Most of the stampless letters until 1855 appeared to be sent unpaid. In the author’s collection of 52 stampless covers originating in or addressed to Quincy, only six were sent paid. These six were either legal or business correspondence.

While the early Quincy town markings were the manuscript type, Quincy was using a town hand stamp by 1835. The same Quincy town mark was used until 1850. While the early markings were in black ink, red and blue inked markings also are

prevalent.

Postmasters in smaller post offices were compensated by a commission on the collected revenue of that office. This commission depended on the amount of the revenue and changed over time. But the commission was in the neighborhood of 40 percent. The rest of the money then went to the Post Office Department. Consequently, net proceeds to the department provide insight into the activity and size of a post office.

The growth of the early Quincy post office can be seen by these net proceeds for various fiscal years (ending March 31): 1827: $6.58; 1828: $22.24; 1829: $46.49; 1830: $136.51; 1831: $109.51; 1833: $187.66; 1835: $278.65; and 1839: $884.72.

Since the early stampless covers were folded sheets, many of them have their original contents. These letters often provide interesting

insights to early

local history.

Although we might expect Quincy to have

been the first post office in Adams County, this was not the case. According to records of the Post Office Department, the Mill Creek Post Office was established in Adams County on Dec. 12, 1825, three months before the Quincy Post Office.

The postal revenue of both the Quincy and Mill Creek post offices was small in the early days. The revenue for the fiscal year ending March 31, 1827, was $6.58 for Quincy and $3.50 for Mill Creek. The next fiscal year ending March 31, 1828, showed revenue of $22.24 for Quincy and $2.43 for Mill Creek. Quincy was starting to grow in activity while the Mill Creek post office was diminishing. The smaller post office closed a few months later.

Jack Hilbing is a retired U.S. Air Force officer. With a doctorate from Stanford University, he has worked with computers in military, industry and academia. He has collected the postal history of Quincy and Adams County for 40 years.