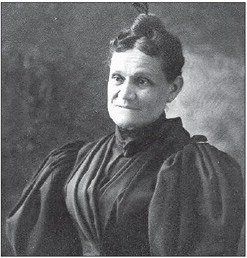

Nurse unselfishly cared for Civil War soldiers

Louise Maertz, 1837-1918, was born in Quincy and lived most of her life there. She was considered to be of a “delicate constitution” and yet managed to work in the field hospitals of the Civil War and to travel extensively.

She never married and devoted her life to writing and philanthropy. She is remembered mostly as a Civil War nurse, the author of “New Method for the Study of English Literature,” published in 1879, and as a member of many civic and charitable organizations.

Maertz began nursing the wounded and sick just a few months after the war began in 1861 in her home and in the hospitals of Quincy, particularly after the battles of Pea Ridge in March 1862 and Shiloh in April 1862. She assisted the surgeon in dressing wounds, visiting the hospital daily. She offered her services and was commissioned as an Army nurse late in 1862 by James E. Yeatman of St. Louis, who was an agent of Dorothy Dix and president of the Western Sanitary Commission. Her first assignment, in the fall of 1862, was in Helena, Ark. There she was responsible for special diets for the wounded. The Rev. Jacob Gilbert Forman, who was secretary of the Western Sanitary Commission, met Louise while stationed in

Helena. He wrote a chapter on her for Linus Pierpont Brockett’s 1867 book “Woman’s Work in the Civil War.”

In the Maertz chapter, Forman describes her as “...always cheerful and kind, preserving in the midst of a military camp such gentleness, strength and purity of character that all rudeness of speech ceased in her presence, and as she went from room to room she was received with silent benedictions, or an audible ‘God bless you, dear lady,’ from some poor sufferer’s heart.”

She was one of the few women in the town. She spent her own money on supplies and went “from one building to another

through the filthy and muddy town…” as there was no hospital.

She remained in Helena five months and twice accompanied the sick and wounded up the Mississippi by steamer to northern hospitals. After the second trip and suffering from exhaustion,

she convalesced

at home in Quincy.

Four weeks later, she was called to the 15th Army Corps Hospital in Chickasaw Springs near Vicksburg Miss. After what she described as “inexplicable delays and unexpected propulsions” or “Government Orders,” with constant worries of snipers and guerrillas intent on setting the steamers and gunboats on fire,

she found herself spending days trying to reach the hospital from the river landing.

She decided to wait no longer for an escort and hitched a ride on an empty ambulance, a journey of 12 miles over hills and ravines. It was dark; she was alone in an unfamiliar landscape and didn’t know the driver. She said, “But a woman who fears is no more fit to be a nurse than is a man who fears to be a soldier.”

Upon reaching her destination, she spent the night listening to the cannonade, which rattled the windows in “the filthiest hole I ever saw,” as she described her cabin. The next morning, she hired a horse and guide to get a view of the “doomed city,” always in danger of a “rebel sharpshooter.”

The entire trip took over 10 days to get to the corps hospital, which had a medical director and eight surgeons and could accommodate 300 patients in three parallel rows of tents.

The other hospital workers were convalescing soldiers. She worked from dawn until 9 p.m. Her duties included getting water from the creek, making poultices and preparing diets.

After the surrender on July 5, she was invited by two of the doctors to visit Vicksburg by horse, a journey of 10 miles.

She described the field

works, rifle pits and artillery ordnance scattered about, the contraband (freed slaves) and Confederates streaming out of the city looking for food, and “the imposing appearance of Vicksburg … with blooming gardens and stately mansions” on the hills. The area was quite hot and damp, and malaria was present. By the end of August 1863, she had malarial fever with night sweats and returned home.

Three months later she was called “to New Orleans to aid in establishing the Soldier’s Home....” After three months she turned over the home in “good running order” to others and went to work at the 13th Army Corps Hospital. She was allowed to work after enduring much difficulty from the senior surgeon, who did not like female nurses.

She worked there throughout the exceptionally cold 1864 winter and stayed until the hospital was “disorganized.”

She was then sent north with other patients as she was sick and remained in Quincy for nine months.

Her last post was to care for exchanged Andersonville prisoners at Jefferson

Barracks south of St. Louis. She remained at the hospital until the last prisoners were discharged. According to the Hospital Muster Roll, she arrived Dec. 16, 1864, and was discharged June 8, 1865.

Maertz was an untrained nurse who saw her work as a service to humanity. She took great pride in the fact that she was never paid for her work, nor did she ask for a pension in her later years.

According to Forman, “In real devotion to the welfare of the soldiers of the Union; in high religious and patriotic motives; in the self-sacrificing spirit with which she performed her labors; in the heroism with which she endured hardship for the sake of doing good; in the readiness with which she gave up her own interests and the offer of personal advantages and pleasure to serve the cause of patriotism and humanity, she

had few equals.”

Arlis Dittmer is a retired medical librarian. During her 26 years with Blessing Health System, she became interested in medical and nursing history — both topics frequently overlooked in history.