Minerva Merrick: Con artists, spiritualists and divorce after death

About 100 years ago in Quincy, the phrase "Til death us do part" acquired new meaning for one woman and her two husbands. Mrs. Minerva Merrick, after enjoying her first 40 years of married life, became the widow of Dr. Charles Merrick in 1876. He left her a wealthy woman, living in a large home on Chestnut Street atop a grassy hill where Third Street terminated at her front gate.

After the passing of the doctor she became interested in life after death and the study of spiritualism. This philosophy, based on the belief that spirits can communicate after death, rose in popularity in the early 1800s and flourished during and after the Civil War with its terrible loss of life. Many prominent people subscribed to these beliefs, including Mary Lincoln, Sir Author Conan Doyle and Mark Twain.

In tribute to her husband's memory, Mrs. Merrick had constructed, at the substantial expense of $8,000, a lovely brick building named Merrick Hall. The building stood at the northwest corner of Fourth and Lind Streets and was used as a meeting hall and lecture venue, and the site every Sunday afternoon at two o'clock of séances and spirit communication.

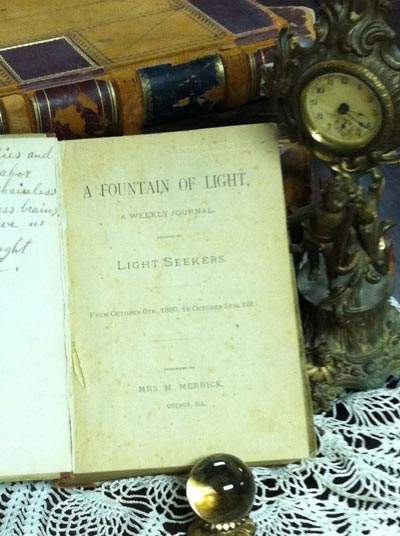

Mrs. Merrick became a mainstay of the spiritualist movement in Quincy. She seized every possible chance to converse with her dearly departed husband through the agency of various mediums and believed that she was receiving direct communication from him. Quincy was a regular stop on the travelling spiritualist circuit, and Mrs. Merrick played host to many of them. She also promoted Spiritualism through her weekly publication called "A Fountain of Light." The circulation for this journal that was printed in Quincy included a geographical area of several states, although actual numbers of subscribers were few.

In short order she attracted the attention of Charles Orchardson, a distinguished looking older man, and his travelling companion, medium Vera P. Ava. Orchardson was the brother of well-known English portrait painter, William Orchardson, and by most accounts a talented painter himself. He was also a proponent of Karl Marx and the Communist Manifesto and sympathetic to anarchists.

Vera P. Ava was an adventuress billing herself as a medium, who was wanted on various charges of fraud and theft as far away as New York City and as close as Elgin. She was short and blue-eyed, weighed more than two hundred pounds, and always wore padded wigs to hide a deformity. Orchardson described her as having "the most remarkable shaped head....The top looks as if it was taken off right down to the ears ... it is the head of one of the lower order of animals and yet she is a woman of great intellectual force, argumentative to the point of brilliancy and daring to the point of desperation." Vera favored blonde wigs and flowing black robes lined in purple satin. One Quincy newspaper referred to her simply as the "Spook Priestess." The pair met and impressed Mrs. Merrick.

A few days later, Elgin Police detective Powers arrived and arrested Vera Ava for stealing money from a widow in his city. Orchardson and Ava had been boarding at the home of the widow Robinson at 827 N. Third, conveniently close to the Merrick estate. Although he had to be restrained by the deputy when Ava was taken into custody, it was only a short time later that Orchardson moved from the boarding house room he had shared with Ava into Mrs. Merrick's home. (Orchardson at the time also had a wife in Michigan, who would divorce him for desertion.) Mrs. Merrick, however, was so fond of him she considered legally adopting the 45-year-old man, claiming he was the son she never had.

A bound copy of the Merrick's "A Fountain of Light" can be found today in the Historical Society library. It offers a fascinating glimpse into Mrs. Merrick's thoughts: she was fervently in favor of women's suffrage and temperance, against "Free Love," concerned with the plight of the poor and orphans in Quincy, and outspokenly against the death penalty. She traveled twice to Missouri to petition the governor for clemency in the case of the two Talbot brothers, who had been sentenced to hang for the murder of their father. When she failed and they were hanged, she eulogized them in her paper.

For some time both Mrs. Merrick and Orchardson quite contentedly wrote and published books and articles on their various philosophies, until a spirit communication changed everything. Mrs. Merrick was told by a male medium (and friend of Mr. Orchardson) that a directive from Dr. Merrick himself instructed his widow to marry again to protect her estate. Minerva, who believed firmly in guiding her actions by both inspiration and otherworldly communication, promptly proposed to Orchardson. He promptly accepted.

The 70-year-old bride and her 45-year-old groom were married on April 12, 1893. Her wedding gift to him by one account was $50,000 in cash. It scandalized the city. But their wedded state lasted just over a year before Mrs. Merrick-Orchardson died (and possibly reunited with her first husband) on June 11, 1894. Fifteen days later, her widower submitted her will for probate.

Soon after that, Vera Ava reappeared in Quincy, newly released from Joliet Women's Prison where she had served two years for theft. She applied for the newly vacated position of Mrs. Orchardson but was soundly rejected. In a rage, she offered her services to the previous Merrick family heirs who had been cut out of the will in favor of Orchardson.

The heirs, two nieces and a nephew, filed suit, saying among other things that Minerva Merrick was "possessed of an insane delusion as to communications from spirits and that she was controlled … by an insane delusion in the making of her will." They carefully said that belief in spiritualism was not an insane belief; but that she had been under undue influence at the time she created her will in favor of Orchardson. A second suit was filed to annul the marriage. It was "in the nature of a post-mortem divorce suit and … tried by the court so that a jury will not be needed." The judge alone would decide.

After much entertaining publicity and courtroom drama and an appeal to the state supreme court, Orchardson lost. The court declared the Merrick-Orchardson marriage null and void, finding there had indeed been "an insane delusion." It took four years after the odd couple had been married, but they were indeed parted after death, rather than by death. And Quincy added another interesting case to its legal history.

Beth Lane is the author of "Lies Told Under Oath," the story of the Pfanschmidt murders near Payson, a member of the Historical Society, and a facilitator of writing and creativity workshops in Quincy.

Sources

This case was covered in all the local papers at Minerva Merrick's death in June of 1892; during the week of April 13th, 1893, at her marriage; and during the trial in December, 1895.

"Dis De Barr's Dilemma." Quincy Herald. January 19, 1895.

Goldsmith, Barbara. Other Powers, the Age of Suffrage, Spiritualism and the Scandalous Victoria Woodhull. New York: Harper Perennial, 1999.

"Jury Has the Case." Quincy Morning Whig. December 21, 1895.

"Married at Eight." Quincy Daily Herald. April 13, 1893.

Martinez, Susan B. The Psychic Life of Lincoln. Franklin, New Jersey: The Career Press, Inc., 2009.

Merrick, M. A Fountain of Light, a Weekly Journal Devoted to Light Seekers, Oct. 6, 1880 to Oct. 5, 1881. Quincy: M. Merrick, 1881.

"Minerva Proposed." Quincy Daily Herald. April 14, 1893.

"Mrs. Orchardson Dead." Quincy Whig. June 14, 1894.

"Orchardson Case Revived." Quincy Daily Whig. November 12, 1899.

"Orchardson Seeks Estate." Quincy Daily Whig. September 29, 1907.

"Suit to Break a Will." Quincy Morning Whig. October 5, 1894.

"Vera is Gone on the Professor." Quincy Daily Journal. January 19, 1895.

"Verdict is Not Approved." Quincy Herald. December 24, 1895.