Presidential Candidate John W. Davis Held Huge 1924 Rally

As Democrats convened in New York City during the summer of 1924 to select a presidential candidate, delegates remained sharply divided over Prohibition, publicly denouncing the politically powerful Ku Klux Klan, and a graduated income tax to aid struggling farmers and the less fortunate. Opposing forces of the 20 candidates whose names had been placed into nomination clashed and tussled through 102 ballots without deciding on a winner.

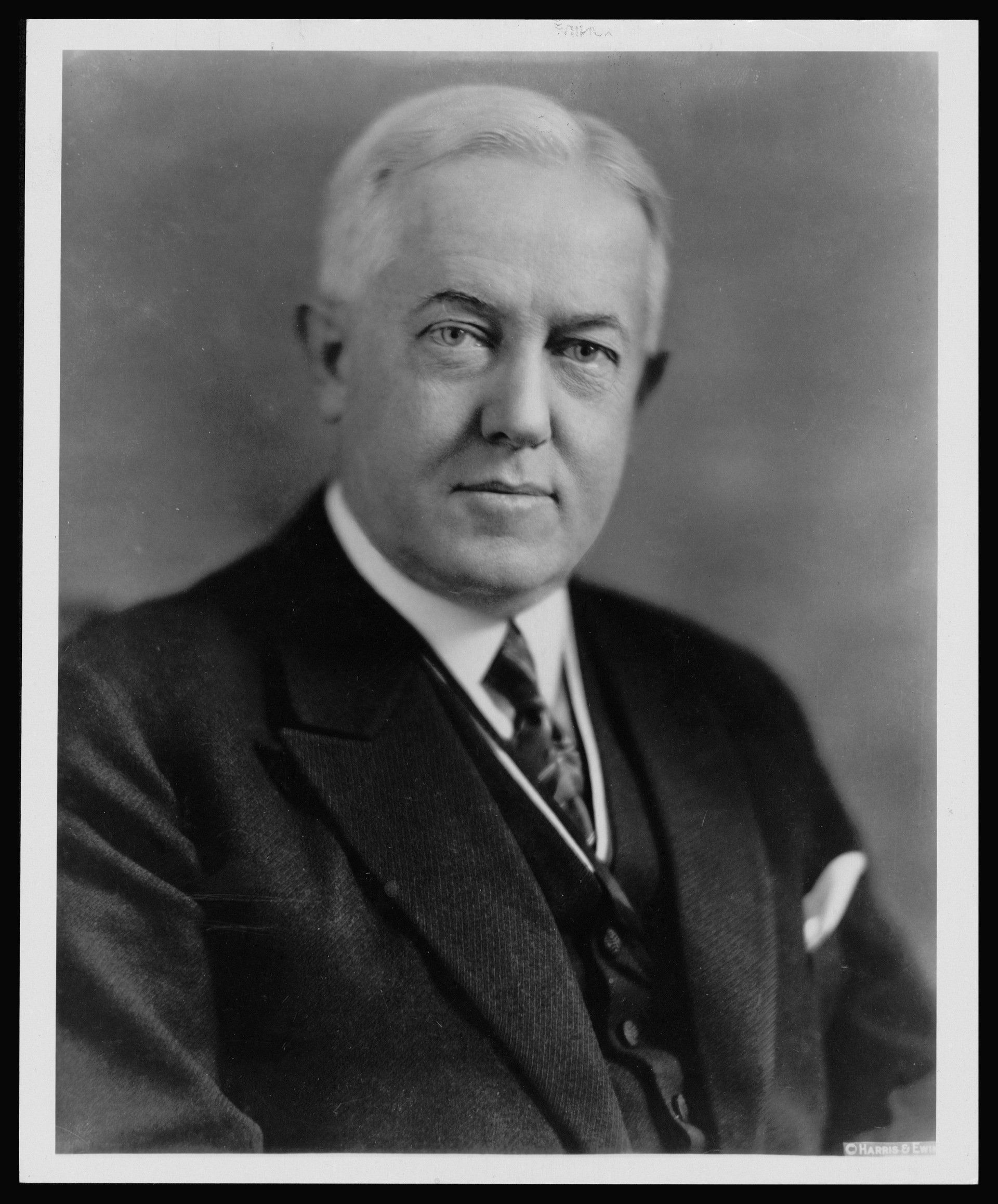

Finally, on the 103rd ballot—the longest in American history—a majority nominated compromise candidate John W. Davis, a scholarly conservative senator from West Virginia and a Wall Street lawyer who did not actively pursue his party’s nod. Quincy Sheriff Ernest J. Grubb served as a sergeant-at-arms and local Democratic Party leader Floyd E. Thompson as one of the vice-chairmen at this convention. Quincyan Emery Lancaster was the only delegate to cast all 103 of his ballots for Davis and he became a close friend and confidant of the nominee.

Davis chose Nebraska Governor Charles Bryan, brother of famed attorney and three-time presidential candidate William Jennings Bryan, as his running mate. This Democratic joint-ticket began a lackluster campaign against sitting President Calvin Coolidge, whose motto “Keep Cool and Keep Coolidge” promised to steer the country on a steady course.

Many people in both the Democratic and Republican Parties believed that Davis and Coolidge’s platforms were too similar to represent the country’s growing liberal views. Wisconsin Republican Senator Robert M La Follette, vowing to end the “orgy of corruption,” formed his own Progressive Party and began a vigorous campaign that undermined support from the two major party candidates.

Soon after the Democratic convention, political leaders in Quincy began plans to bring Senator Davis to town. They formed committees and established a headquarters at 508 Hampshire, which also housed a Davis-Jones Club to support the presidential candidate and Judge Norman L. Jones of Ottawa for Illinois governor. Davis accepted an invitation to speak at Baldwin Park on October 15, 1924, the first presidential candidate to visit Quincy since William Jennings Bryan campaigned here in 1896.

Although Davis had not supported the 19th amendment to the U. S. Constitution granting women suffrage in 1920, planners reserved 100 seats at Baldwin Park for females attending the speech. The new medium of radio had provided live broadcasts of the Democratic convention. Campaign workers for Davis required local radio coverage of his speech and amplifiers at Baldwin Park. Quincy electrician Russell Williams furnished them. City Alderman Louis F. Fuelbier formally welcomed the senator and Mayor William B. Smiley proclaimed it “John W. Davis Day.” Former Quincyan Fred Haskins, who lived in Washington D. C. and worked as a correspondent for local papers, provided readers with detailed reports.

Following a luncheon at the Hotel Quincy, a parade escorted Davis through downtown and then to Baldwin Park, where a crowd estimated at 12,000 people had assembled. This number included an entourage of reporters and photographers from major newspapers around the country and trainloads of spectators from surrounding counties in Missouri, Illinois, and Iowa. Many local stores closed and allowed employees to attend this once-in-a-lifetime event. The Eagles Club Band of Quincy and the Illinois State Band of Springfield played patriotic music, while vendors and political groups handed out literature and curios.

Davis’ speech differed significantly in a couple of ways from his standard campaign oration. Because of Prohibition’s unpopularity in this area, he did not mention his endorsement of the 18th Amendment to the Constitution enacted five years earlier that banned the sale, manufacture, and consumption of alcohol and now sharply divided the country between “wets” and “drys”. Also, aware of strong local support for the Ku Klux Klan, he did not openly condemn this organization as he had during most other campaign stops. President Coolidge, though, fearful of a backlash, never publicly censured the KKK by name during the entire 1924 political season.

Senator Davis stated that national and local politics are inextricably bound. A transcript published in the Quincy Daily Herald of October 16, 1924, included this passage: “You cannot have good government in Washington, unless you have it in Adams County. You cannot have good government in Adams County unless you have it in Quincy. Government in the United States hails from the bottom up, and not from the top down.”

In his one-hour speech, Davis said that the Teapot Dome scandal of the previous Harding administration had shocked the country. He warned that several of the “corrupt” cabinet members and officials embroiled in that notorious crime still served in Coolidge's current administration. In response to the growing divide between urban and rural America, he assured local farmers that he would help them, and vowed to bring fairness, honesty, and integrity back to Washington.

On November 4, 1924, voters went to the polls. Results surprised few observers: President Coolidge won in a landslide, with 15.7 million votes (382 electoral votes) to Davis’ 8.4 million votes (136 electoral votes). La Follette garnered 4.8 million votes and 13 electoral votes from his home state of Wisconsin. The president’s coattails extended to the state level, where Illinois Republicans won the governor’s race and the 20th Congressional District.

The tally in Quincy proved even more lopsided than the national numbers. In the lowest percentage turnout of eligible voters for a presidential election in local history, Coolidge received 1,223 votes to only 52 for Davis. Democrats running for Quincy offices, though, split the ticket. They revamped their forces and looked to the future.

In 1928, Democrats won three out of every four local elections, the same year that Republican Herbert Hoover entered the White House. One year later, the stock market crashed and the Great Depression began. Hoover would be the last Republican president until 1952. During that 24-year span, Quincy voters elected four consecutive Democratic mayors and strongly supported—with the endorsement of John W. Davis—every Democratic presidential candidate.

Sources

“Coming to Quincy.” Quincy Daily Herald , Oct. 11, 1924, 1.

“Democratic Party in Adams County,” in People’s History of Quincy and Adams County. Rev. Landry Genosky O. F. M, ed. Quincy, IL: Jost & Kiefer Printing Co., 1973, pp. 274-80.

“Democrats Will Split, Says Illinois Delegates to Convention.” Quincy Daily Herald , June 26, 1924, 1.

“Extend Formal Greetings to John W. Davis.” Quincy Daily Journal , Oct. 14, 1924, 12.

“John W. Davis Pleased With Quincy Reception, Candidate’s Busy Life.” Quincy Daily Herald , Oct. 16, 1924, 1.

Murray, Robert. The 103rd Ballot: The Legendary 1924 Democratic Convention That Forever Changed Politics. New York: Harper & Row, 1976.

“Nomination of Davis Brings Joy to Most Democrats of Quincy.” Quincy Daily Herald , July 10, 1924,14.