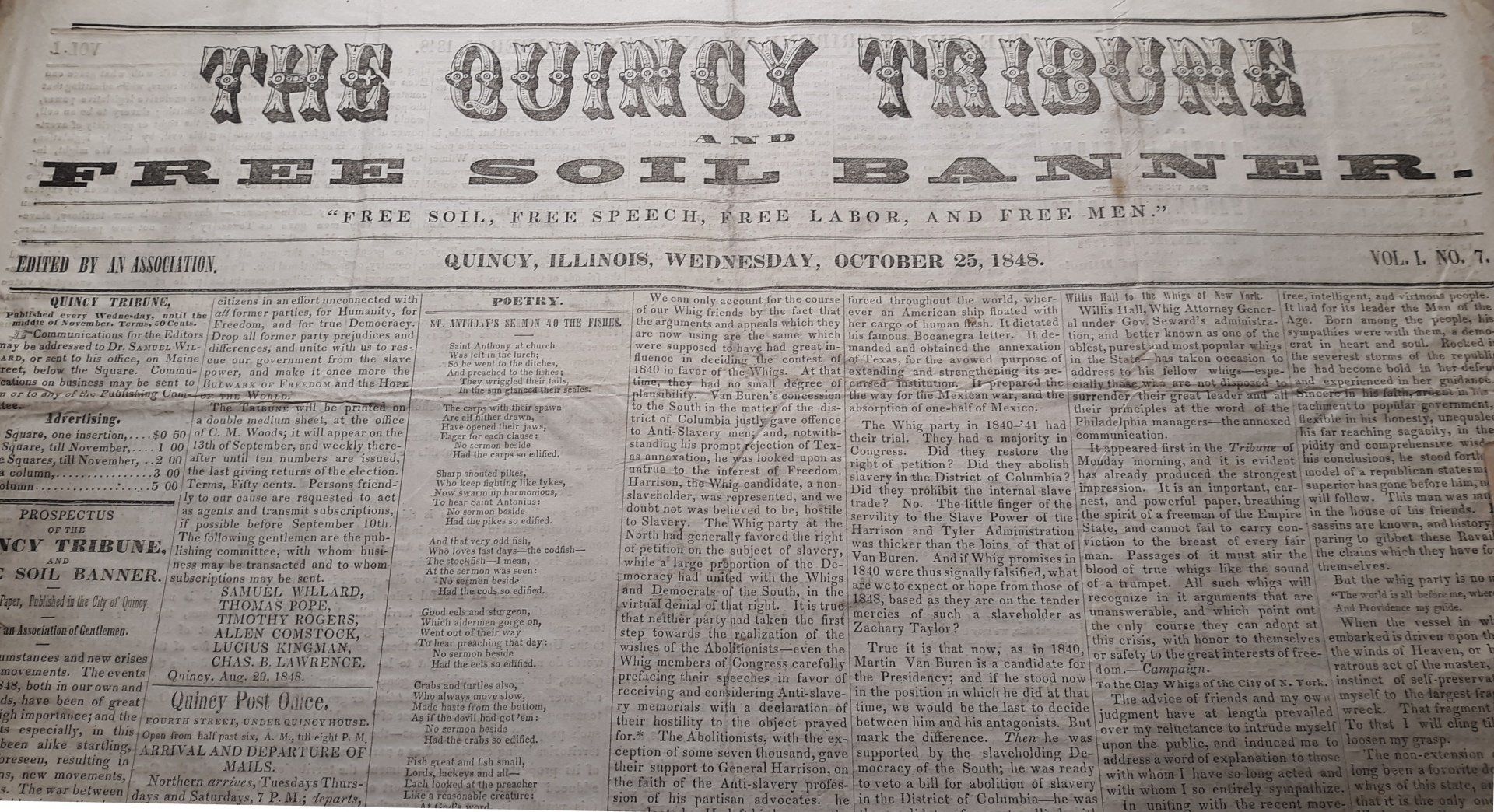

The Quincy Tribune and Free Soil Banner

In presidential elections third-parties periodically pop up like morels in the spring and disappear just as quickly. Challenging the Whig and Democratic Parties in the 1848 canvas was the Free Democratic Party, or as it became known---the Free Soil Party.

The Mexican American War beginning in 1846 and ending in 1848 brought forth the political question of the day. Would slavery be allowed in the newly acquired territory of Texas, New Mexico, and California? Three times the House of Representatives passed legislation banning slavery there, and each time the Senate voted it down.

With the incumbent, James K. Polk not seeking reelection, the field was wide open. For many it was time to stop the spread of slavery, and these Americans held out that it could be done by the electoral system.

The Whigs selected Gen. Zachary Taylor, Mexican War hero, southern planter, and owner of 150 slaves, as their candidate. The Democrats chose Michigan Senator Lewis Cass. Cass sidestepped the issue when he called for “popular sovereignty.” He declared a territory’s settlers should make the decision on whether to allow slavery or not.

Both the antislavery Whigs and Democrats were disillusioned with their respective nominees. These disgruntled voters joined with the Liberty Party to oppose the growth of slavery. At a convention in Buffalo, they formed the Free Soil Party and nominated Martin Van Buren.

To promote the Free Soil Party locally, a ten-issue campaign newspaper was published in Quincy and distributed area wide. Officially it was called The Quincy Tribune and Free Soil Banner . Behind the venture were Samuel Willard, Thomas Pope, Timothy Rogers, Allen Comstock, Lucius Kingman, and Charles B. Lawrence.

The Free Soil Banner’s editorial committee wrote that “the Democratic party has long been . . . ‘the natural ally’ of slavery” while “the Whig party shows a double front: in the North professing free principles, in the South defending slavery. . . .” The Free Democracy [Free Soil] party “is composed of the leading opponents of the Slave Power. . . .” Men who “wish to forbid the introduction of slavery into new territories; to put an end to it wherever it exists under the authority of the general government, and to throw the influence of the nation against slavery and in favor of liberty . . .” Men who stand for “Free Soil, Free Speech, Free Labor, and Free Men.”

The committee asked area voters “to drop all former party prejudices and differences, and unite with us to rescue our government from the slave power, and make it once more the BULWARK OF FREEDOM and the HOPE OF THE WORLD.”

The Whig candidate Zachary Taylor won the election and became president but lost Illinois by 3,247 votes. Statewide the Free Soil Party garnered 15,774 votes with Adams County providing 251.

The Banner’s last issue pointed out the irony of the election. They wrote that the Whig Party nominated a man for president simply due to his success in war. A conflict the Whig Party “branded as an unjust war.”

Not defeated, the Free Soil Quincy committee stated that the struggle to end slavery would “be long and difficult, but this world and this country don’t belong to the devil, and there is no doubt of the final result.”

What became of the six men who published The Quincy Tribune and Free Soil Banner ?

In 1848, Samuel Willard was a Quincy physician and an abolitionist. Before Quincy, the Willard’s family home in Jacksonville was a station on the Underground Railroad. In February 1843, both Samuel and his father, Julius, were caught, convicted and fined for assisting a runaway slave. Dr. Willard continued in politics and was a secretary at first Illinois State Republican Party convention in 1856. During the Civil War, he served as a regimental surgeon with the 97th Illinois Infantry.

Thomas Pope’s family came from New York to Quincy in 1837. Over the next 60 years Pope partnered in a number of Quincy retail businesses. His first presidential vote was for the Liberty Party’s James G. Birney in 1844. He had “at all times and under all circumstances . . . the courage of his convictions,” wrote the Daily Herald at Pope’s death in 1900. This was especially true “during the troublesome and critical times preceding the rebellion. . . .” His oldest son “gave his life for his country in the Civil War.”

Timothy Rogers came to Quincy from Connecticut in November 1838, and practiced his trade of wagon maker. At his death in 1889, the Quincy Whig wrote that at one time Rogers had “the largest wagon factory in the west.” For a number of years he owned and operated Quincy’s Occidental Hotel.

Allen Comstock arrived in Quincy in the mid-1830s and opened a general store. In 1846, he and his brother Enoch built a foundry and began manufacturing stoves. Timothy Castle and Frederick Collins became partners in the fledgling company, which still operates in Quincy today.

Lucius Kingman settled in Quincy in 1830. Kingman was John Tillson’s partner in the real estate and land business. At his death in 1882, the Daily Whig stated with the arrival of the government land office in Quincy in 1836, “Mr. Kingman was perhaps more associated with land transfers than any other person in this part of the State.

In 1845, Charles B. Lawrence, a Middlebury College graduate, came to Quincy to practice law. The Herald’s obituary stated that he was associated with Archibald Williams, and “this firm was recognized . . . as one of the ablest in the State.” Lawrence left Quincy in 1856, settling in Galesburg where in 1859 he was elected circuit judge. In July 1864, Judge Lawrence was elected to the state Supreme Court and later served as the Chief Justice. At his death in 1883, a letter to the Herald commented that Lawrence “earnestly espoused the Free Soil movement of Van Buren and Adams.”

Sources

Boyer, Paul S., Ed. In Chief, The Oxford Companion to United States History , New York: Oxford University Press, 2001.

The History of Adams County, Illinois , Chicago: Murray, Williamson & Phelps, 1879.

Jacksonville Daily Journal , February 12, 1913.

Kofoid, Carrie P., “Puritan Influences in Illinois before 1860,” Transactions of the Illinois State Historical Society for the year 1905, Publication No. 10, Springfield, Illinois: Illinois State Journal Co., State Printers, 1919.

Nevins, Allan, Ordeal of the Union, Fruits of manifest Destiny 1847-1852 , New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1947.

Quincy Daily Herald , April 21, 1900; February 10, 1913.

Quincy Daily Journal , April 14, 1897; January 7, 1889.