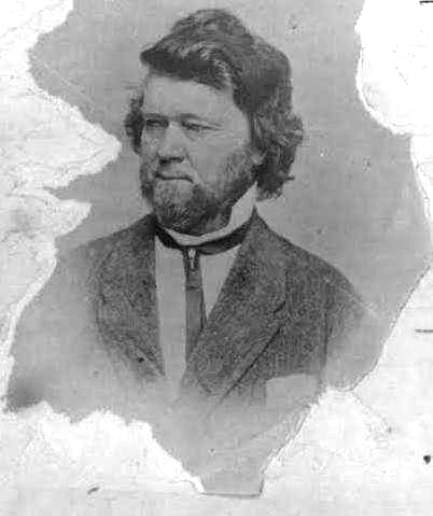

Quincy attorney played part in ill-fated constitutional convention

Illinois' second constitution, expected to remedy the ills of the first, had its own problems.

So, when Illinoisans in November 1861 approved another convention to replace the constitution of 1848, James W. Singleton of Quincy would give it his second try. Singleton had been a delegate to the 1847 constitutional convention, and he was one of three delegates to that convention who sought a role in rewriting it.

Constitutional concerns about banking in Illinois, the powers of the three branches of state government, local governments, immigration and issues related to free blacks in Illinois awaited the delegates. They convened in Springfield on Jan. 7, 1862. Singleton had other reasons for wanting to participate. Ultimately, those reasons would strike dissonant chords for the new president, Abraham Lincoln, embarrass the current governor, Richard Yates of Jacksonville, and trouble the previous one, Singleton's neighbor, John Wood of Quincy.

Born in Paxton, Va., in 1811, Singleton at age 17 interned in medicine with his father-in-law in Kentucky. Unable to develop his own practice there, he moved to Mount Sterling in 1834, where he practiced medicine and studied law. He was admitted to the Illinois Bar in 1838. At the end of his second term as state representative from Brown County in 1854, Singleton and his second wife, Parthenia McDannald, and their two children moved to Quincy. His first wife and son had died.

Singleton's shaky relationship with Lincoln was aggravated in 1848 when Lincoln endorsed Mexican War hero Gen. Zachary Taylor for president over the Whig Party's persistent presidential candidate Henry Clay. Lincoln had given up on Clay. His party, Lincoln said, had fought long enough for principle and should now seek to win an election. Clay was strong among old-line Illinois Whigs like Singleton, who berated Lincoln for "swaps and trades."

"Lincoln's ambition," said Singleton, "is his besetting sin."

When the Whig Party's credentials committee met at the beginning of the 1848 national convention in Philadelphia, Lincoln tried unsuccessfully to keep Singleton, committed to Clay, from being seated. Singleton's participation did not matter. Taylor won the nomination and the presidential election.

When U.S. Sen. Stephen A. Douglas' Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854 irretrievably split the Whig Party north and south, Singleton declined to join Lincoln in Illinois' new Republican Party and became a Douglas Democrat insider. It was Singleton who revealed in a letter to the Richmond (Virginia) Examiner that Douglas' friends "will present his name as a candidate for the presidency ... to the (1856) Cincinnati convention."

Singleton's absence from a rally outside the Adams County Courthouse on April 13, 1861, the day after Confederates bombarded U.S. Fort Sumter, was misread. Speaker Orville Hickman Browning of Quincy pointedly told the large crowd gathered to support President Lincoln in his call for 75,000 volunteers that Singleton was absent. In the days ahead, The Quincy Whig explained that Representative Singleton at the time had been working in the Legislature, where he sponsored a bill to establish an armament factory and arsenal in Quincy.

Singleton declined Governor Yates' offer to commission him a colonel over a cavalry regiment that had been approved for Illinois. Singleton answered Gen. John Pope, who implored him to accept the commission: "Whilst I acknowledge my duty to the federal government and my obligations to the state of Illinois that has honored and protected me for 30 years, I must in the candor of friendship confess that I cannot bury my affection for my native state or forget my numerous kindred and friends who are to suffer for the treason of others."

Singleton was sharply critical of Lincoln's handling of the Civil War, considering the president's actions arbitrary and unconstitutional. Lincoln had suspended habeas corpus, called for states to send militia men, authorized expenditures of millions of dollars for the construction of several ships, imposed blockades of Southern ports, and more, all without congressional approval.

With only 21 Republicans seated, the 45 Democratic delegates convened the 1862 constitutional convention in controversy. They refused to take the oath prescribed by the Legislature's enabling act, considering it illogical to support a constitution they had been elected to change. They drafted their own oath. Worse, the delegates declared that once organized, the law establishing the convention was no longer binding on them. Delegates gave themselves "supreme authority" for altering the constitution.

Delegates took on a quasi-legislative role from that point on, adopting reapportionment and redistricting schemes that favored Democrats, calling for the eviction of Orville Browning, whom Gov. Yates had appointed to succeed the deceased Sen. Stephen Douglas, from the U.S. Senate, and seeking to remove statewide officeholders like Yates after new midterm elections.

With this authority, delegates appointed Singleton chairman of a committee to investigate how well the Yates administration supported Illinois troops sent to war. Though aimed at embarrassing the governor, it was a direct attack on the management of John Wood, whom Yates on April 19, 1861, had appointed Illinois' quartermaster general. If the committee found malfeasance, they were "instructed to inquire further whether the neglect is justly chargeable to any person or persons holding office under this state."

Singleton issued the committee's report on March 13, 1862. "With few exceptions," went the report, "all (committee members) unite in saying that the troops of Illinois have been and continue to be provided for in all respects as well as if not better than the troops sent into the field from any other state."

For the public's reaction to the maverick convention, a resolution by Quincy Daily Herald publisher Austin Brooks, a Democratic convention delegate, was the last straw. Brooks demanded an investigation to determine whether the "treasonable doctrine of secession has not received its vitality and nourishment from abolition leaders of the north. ..."

Alarmed by the impropriety of convention delegates, Illinoisans demanded delegates do the job for which they were elected. The constitution was a loser before it left the convention. Of the 75 members present, 29 -- including Singleton -- did not vote. It was sent to the state's electorate, where Illinoisans rejected it 141,103 to 25,052 in a special election June 17, 1862.

Reg Ankrom is a member of the Historical Society of Quincy and Adams County. He is a local historian, author of a prize-winning biography of U.S. Sen. Stephen A. Douglas, and a frequent speaker on Douglas, Abraham Lincoln, and antebellum America.

Sources:

Reg Ankrom, "A Quincy lawyer was last to meet with Lincoln," Quincy Herald-Whig, August 28, 2016.

"John Wood and the Peace Conference of 1861," Quincy Herald-Whig, Sept. 4, 2013.

Peter J. Barry, "General James W. Singleton: Lincoln's Mysterious Copperhead Ally." Mahomet: Mayhaven Publishing, Inc., 2011, pp. 34, 35, 40, 60, 63, 67.

Frank Cicero Jr., "Creating the Land of Lincoln: The History and Constitutions of Illinois, 1778-1870." Urbana: University of Illlinois Press, 2018, pp. 169-170.

Janet Cornelius, "Constitution Making in Illlinois, 1818-1970." Urbana, Ill.: University of Illinois Press, 1972, p. 48.

David Costigan, "A City in Wartime: Quincy, Illinois in the Civil War." Ph.D. dissertation, Illinois State University, 1994, p. 73.

"Gen. Singleton," The Quincy Daily Whig, Aug. 28, 1862.

"Great Speech of General James W. Singleton at Jacksonville, Illinois," The Quincy Daily Herald, Sept. 24, 1858, p. 2.

Phil Reyburn, "John Wood: Illinois' Civil War quartermaster general," Quincy Herald-Whig, Jan. 23, 2014.

"Remarks of Gen. J.W. Singleton," Daily Herald, April 3, 1862, p. 2.

Singleton, James Washington, (1811-1892), "Biographical Directory of the United States Congress, 1774-Present."

"Singleton & Brooks," The Quincy Daily Herald, July 18, 1863, p. 1.

"United States Arsenal at Quincy," The Quincy Whig, May 4, 1861, p. 3.