Quincy colonel an eyewitness to Lincoln's death

Quincyan George V. Rutherford unexpectedly took the role of special correspondent to the Quincy Whig and Republican when he was in Washington and a participant in the unfolding tragedy on the evening of Good Friday, April 14, 1865, when President Abraham Lincoln was shot at Ford’s Theatre.

Col. Rutherford was in a position to offer an eyewitness account of what he referred to as the most “diabolical, demoniacal, . . . and truculent assassination” known to history.

Rutherford, assistant quartermaster of the Union Army serving directly under Quartermaster Gen. Montgomery Meigs since 1863, closely saw one of history’s most tragic episodes.

He spent a night of vigil as guard at the Petersen House, where Lincoln lay dying after being shot by John Wilkes Booth at Ford’s Theatre, just across the street.

With the presence of mind to preserve the history he had just witnessed, Rutherford recorded an especially valued primary source for historians. After 33 hours without sleep, the colonel returned to his boardinghouse and wrote his account of the “most lamentable tragedy.”

Rutherford sent a telegram in the early morning of April 15 to the Quincy Whig relaying the assassination and stating the president “is just expiring.” The account of his participation was sent by letter and published April 24, 1865.

Rutherford recounted his steps within moments of the assassination as he worked to ensure that key officials were notified. He then went to the home of Meigs, and the two of them went to the home of Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton. Meigs directed Rutherford to assume command of Stanton’s premises because it was not known if he, too, would be targeted. He did so until 1 a.m., when he was directed to join Meigs at the Petersen House at 1:30 a.m.

Rutherford entered the 9.5-foot by 17-foot bedroom where Lincoln lay surrounded by Cabinet members, Sen. Charles Sumner, Speaker of the House Schuyler Colfax, Illinois Gov. Richard J. Oglesby, Surgeon Gen. Joseph K. Barnes, Gens. Henry Halleck and Meigs and others.

Just a few feet away, several officers set up a command center. Maj. Thomas T. Eckert, superintendent of military telegraphs, was issuing the orders of Stanton for the capture of the assassins. The telegraph was steadily sending messages to close roads, and in the small adjacent parlor,

Mary Todd Lincoln was weeping.

Rutherford stood guard outside the house until 6 a.m. when he took a break to eat.

It is likely at this point the telegram to Whig editors was sent, notifying Quincy of the president’s death. Rutherford returned to the Petersen House about 10 minutes after Lincoln died.

Rutherford’s detailed report to the Whig and Republican described Lincoln’s head wounds. He described where the bullet entered the president’s head on the left side at the base of the posterior portion of the brain, passing through and lodging near the “right eye and causing both to protrude to a considerable extent, and to turn black in a very short time.”

The wound was “sufficient to prove an immediately fatal one to an ordinary man; but Mr. Lincoln’s iron constitution refused to yield to death until twenty-two minutes past seven this morning.”

Stanton then directed a particular honor to Rutherford.Rutherford was asked to place the “coppers” on Lincoln’s eyes.

Rutherford recounted that after doing so he remembered he had a silver half-dollar in his pocket that had been given to him by General Benjamin.H. Grierson of Jacksonville, Ill., as a keepsake.

Rutherford obtained another silver half-dollar and placed the two silver half dollars on Lincoln’s eyes in place of the pennies. The colonel poignantly wrote that it was “so small a function in connection with so great a man.”

In the confusion of who should do what, it was Rutherford who suggested to Gen. Christopher Augur, commander of the Department of Washington, that bells should be rung throughout the city. The order was given.

Shortly after 8 a.m., Rutherford, along with Col. Louis Pelouze of the War Department, was directed to take charge of the body of Lincoln until it was moved to the White House.

An hour later, a plain box arrived, and the body was escorted by troops. Rutherford, Pelouze, Augur and Daniel Rucker were in charge of the hearse. Upon arriving at the mansion, the body was taken to the front room on the second floor, where the box was placed on chairs, reported Rutherford. No one but those mentioned and the undertaker and his assistant were in the room.

Stanton, who had become a close friend and admirer of the president, “then placed both hands upon the box, leaned forward, bent over, and wept.”

Rutherford and Augur remained in charge of the president’s body until noon, when they were relieved. Lincoln’s longtime Quincy friend, Orville Browning, was an honorary pallbearer and had been the only non-military and non-medical person at Lincoln’s autopsy. Rutherford returned to Quincy within days after the assassination.

Rutherford is one of three who claimed to have placed two large coins on Lincoln’s eyes after his death. However, his quick thinking to immediately document his actions is a strong indication of the reliability of his assertion.

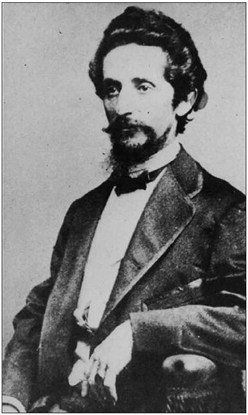

Retiring with the rank of brigadier-general, Rutherford lived in Quincy until 1872. After a brief time in California, he died there at age 42 on Aug. 28, 1872. Born in Rutland, Va., in 1830, he had passed the bar in Virginia, supervised the construction of telegraph lines in Southern states, and in 1862 became the assistant to former Gov. John Wood, quartermaster of Illinois. His brother Reuben Rutherford arrived in 1856, later went to wrar and worked with the War Department until 1867 when he returned to Quincy.

Rutherford is depicted in an 1865 account of Lincoln’s death by Alonzo Chappel, an artist who specialized in historical scenes. The piece, titled “Last Day of Lincoln,” shows Rutherford standing in the rear to the right, next to Stanton.

Iris Nelson is reference librarian and archivist at the Quincy Public Library, a civic volunteer and member of the Lincoln-Douglas Debate Interpretive Center Advisory Board and other historical organizations. She is a local historian and author.