Hospital struggled to establish training for nurses

When Blessing Hospital opened in 1875, it had a physician on call and a small housekeeping staff but not a trained nurse.

St. Mary Hospital had the Sisters of the Poor of St. Francis who arrived in 1866 and were trained through religious life to care for the sick and indigent.

In 1878, the Blessing Board of Trustees established a Board of Lady Managers to provide organization for the fledgling hospital.

The Lady Managers hired a trained nurse, Elmira C. Davis, a recent graduate of Bellevue Training School for Nurses in New York City, to be superintendent with a salaryof $500 per year.

Davis was “to give instruction to others in the duties of her profession whenever requested by the society.”

Thus from the very beginning of their tenure, the Lady Managers were concerned about the quality of nursing care and regularly wrote about the need for a nursing school at Blessing.

There were several attempts to start a school but all failed due to lack of money, lack of properly trained staff to organize and run a school, lack of acute patients on which to gain experience and lack of pupils. The hospital was totally supported by donations.

Married women were not expected to work, and unmarried women sought a career when they had a financial reversal or a father or husband who left no support.

The hazards of nursing included fatigue and sickness, and it was not common for a nurse to die. There also was the question of “unsuitability” such as tardiness, rudeness, lack of respect for patients and the inability to do the work, which led to a high attrition rate.

In 1881, Miss Hutchinson arrived from Boston Training School. The Lady Managers wrote in 1882, “a hospital without a skilled nurse was an anomaly which often threatened to prove too much for us, and if repose of mind counts for anything (to say nothing of the patient’s comfort), we have had ample returns from our investment.”

Regrettably, nothing came from that attempt to start a school, and by 1887 the Lady Managers were corresponding with an order of Lutheran nursing sisters from Germany only to again be disappointed. Their annual report of that year said, “For a long time we have felt the need of supplying nurses who have not drifted into the profession for want of something else to employ them. We desire to secure two trained nurses and establish in connection with the Hospital, a training school.”

And again, the 1888 Annual Report of the Board of Lady Managers said, “We desire to establish in connection with our work, a training school for nurses. Is it not time that the care of the sick and suffering be taken by common consent out of the hands of those who take up nursing as a last resort. Inexperienced, undisciplined and too often preoccupied with their own discouragement and trials — what kind of a person is this to trust with the intricate, delicate, and responsible duties of the sick chamber?”

In 1891, Mrs. Marsh of the Lady Managers went to Chicago to visit St. Luke’s Hospital School of Nursing and find a trained nurse.

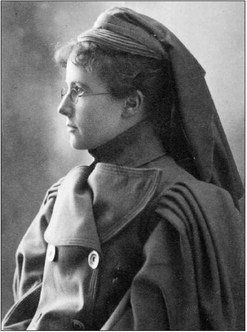

She interviewed Miss Farrar, who agreed to come to Blessing Hospital and start a school.

This time, obstacles were overcome and Miss Farrar arrived, “Her presence was an assurance that the object so long wished for, so earnestly worked for was an established fact, a training school soon to be started.”

Money was raised and housing was secured for the students.

Miss Farrar set up an application process with the Lady Managers reviewing each candidate.

Letters of recommendation were required from a physician establishing good health and from clergy establishing good character. Candidates had to be “refined with a pleasing appearance and gentle manners.”

They had to be 23 years old and have completed the eighth grade. Blessing Hospital Training School for Nurses was established as a two-year program with one month of probationary status.

At the end of probation, the student nurses were allowed to wear a uniform.

The curriculum consisted of bedside training in patient care and lectures from the attending physicians and from Miss Farrar. It was learning by doing rather than learning by pedagogy.

As hospital-based nursing schools had no independent budget, they had to follow hospital dictates that meant bedside work, night classes and long days. Student nurses were a stable workforce. Their education was considered fair value for their service to the hospital.

This was the Victorian Era, and the ideal woman worked hard, was loyal and did no harm.

The hospital was the guardian of the school and the nurses, with hospital needs taking precedence over school needs.

After only a few months, Miss Farrar resigned, complaining the “beds were filled with chronic cases and not one was suitable for providing any instruction to pupil nurses.”

Once again the Lady Managers were disappointed. But after three more years of starts and stops, with a number of trained nurses providing patient care and student instruction, the first class of three nurses graduated in September 1894.

In December 1894, Mrs. E.J. Parker read a paper before the Women’s Council of Quincy in which she said, “The primary object of the training school is to provide better care for the hospital patients, for whom we are directly responsible; but as soon as it became known that our nurses were also available for outside cases, a demand for them began which has increased rapidly.”

Nursing education started small at Blessing Hospital but has grown and continuously provided thousands of nurses for over 120 years.

Arlis Dittmer is a retired medical librarian. During her 26 years with Blessing Health System, she became interested in medical and nursing history — both topics frequently overlooked in history.