Quincy had two senators during Civil War

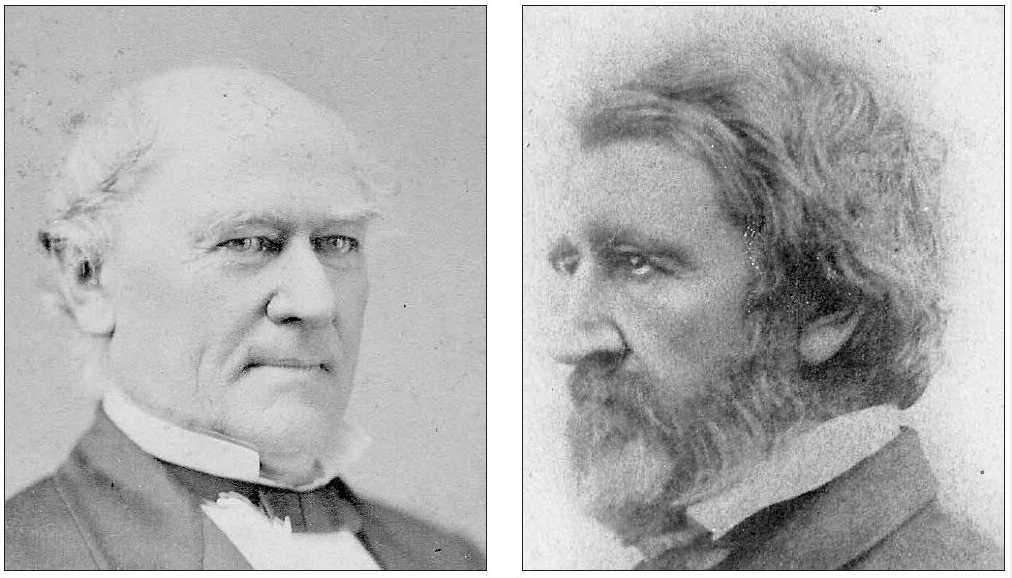

Stephen A. Douglas was a dominant force in the U.S. Senate from 1847 until his death on June 3, 1861. Filling his vacated seat fell to Illinois Gov. Richard Yates. Some demanded that he name William A. Richardson, Douglas’s foremost lieutenant, to the seat, but the Republican governor was not about to name a Democrat in this critical time so soon after the onset of the Civil War. Thus he turned to the well-respected Quincy attorney and former state legislator, Orville Hickman Browning. For Browning, a close personal relationship with President Abraham Lincoln was a valuable asset.

The newly appointed Illinois senator headed to Washington to attend the special session called by the president to commence on July 4, 1861. The main business before Congress was to address the presidential initiatives taken in response to the Confederate firing on Fort Sumter on April 12, the beginning of the war. Lincoln declared the South in rebellion, called up military volunteers, used funds without congressional authorization, and suspended the writ of habeas corpus between Philadelphia and Baltimore. These dramatic but controversial initiatives were fully supported by Browning. During the session, Browning spoke in the Senate, declaring that since slavery caused the war, there should be no legitimate complaint if ending slavery should become an objective of the war. The special session ended on Aug. 6, and because of his unstinting support of the President, Browning was generally adjudged as a radical. During the abbreviated session, Browning frequently visited the White House, often going in carriages sent for him by Lincoln. Browning was Lincoln’s eyes and ears in the Senate. The new senator headed back to his home in Quincy with a four-month wait until the next session of Congress would resume in December of 1861.

Before the next session of Congress commenced, a remarkable sequence of events occurred challenging the relationship between Lincoln and Browning. On Aug. 30, 1861, General Fremont, Commander of the Western Department, issued a proclamation of emancipation for Missouri. Missouri was a slave state that had remained loyal to the Union, although rebel guerrillas abounded in the state. Lincoln rejected Fremont’s initiative and revoked the document. On Sept. 17, Browning wrote the President expressing regret over Lincoln’s revocation. Browning wrote, “Have traitors warring on the Constitution and the laws any right to invoke their protection?” Lincoln responded with an often quoted reply, “Your letter astonishes me. The proclamation is purely political … it is simply dictatorship … I think to lose Kentucky is nearly the same as to lose the whole game.” The reference to Kentucky represented Lincoln’s concern that losing any of the loyal slave states could turn the balance of power in the direction of the Confederacy. Browning responded with a 13-page letter of justification for his position. In summary it said, “I do think (Fremont’s proclamation) was fully warranted by the laws of war.” He cited legal sources that Lincoln obviously took seriously, for he appointed Francis Lieber to research and formulate a codification of the laws of war. Lincoln accepted the code in early 1863, and this became a permanent commitment of the United States in wartime. Lincoln used Browning’s suggestions from the long letter as his justification in the Preliminary Emancipation Proclamation of Sept. 22, 1862, and in the final proclamation of Jan. 1, 1863.

In his final congressional session as senator, Browning became a voice in opposition to most Republican party initiatives. He condemned the Second Confiscation Act that provided for the freeing of slaves of persons in rebellion. He counseled Lincoln to veto it and the President indeed wrote a veto message but strangely went ahead and signed the bill. It might be noted the bill was never enforced. Browning likewise opposed admitting the state of West Virginia as an unconstitutional act because it did not secure the support of the Virginia legislature. Still Lincoln reluctantly signed the measure. Browning addressing issues at the end of his term was a dramatic contrast to the earlier Browning, who was so condemnatory of secessionists and of the institution of slavery in general. Historian Mark Neely commented, “There is no explaining the suddenness of his (Browning’s) change, but it was a reversion to an accustomed conservatism rooted, in part, in old-fashioned racial views.”

Ironically, Browning, the man who had suggested the rationale for the preliminary Emancipation Proclamation, now called it politically disastrous. Historians rarely recognize that the ordinarily politically astute Abraham Lincoln sacrificed the political advantage of his party by his summary issuance of the document in September 1862. An issuance after the fall elections, while substantially changing nothing regarding emancipation, would have avoided the drastic loss of seats by his party in Illinois, Indiana, and Ohio. The proclamation for which he had provided a legal rationale he now termed “disastrous.” It ensured that he would be replaced in the Senate by a Democrat.

In the mid-term elections of 1862, the state of Illinois produced a dramatic reversal in political fortunes. The Republican majority in the state house, which accompanied Lincoln’s presidential victory in 1860, gave way to a shocking victory for the Democrats. With a 22 seat majority in the lower house and a margin of one in the state senate, a Democrat U.S. senator was assured. The party held a caucus to choose its candidate and selected Quincyan William A. Richardson by a handsome margin over his closest Democrat rival. On Jan. 12, the Illinois Assembly met and selected Richardson by a vote of 66-37 over the nominal Republican choice, Gov. Richard Yates. Ordinarily, Quincy would respond by bells and cannon shots, but these were suspended due to the recent death of the Richardson’s youngest daughter.

Rather than elation, there was a pall over his election victory as Richardson left for Washington. He assumed his new duties with a heavy heart, complicated by serious health issues faced by his oldest son, and especially by his wife Cornelia. In the Senate, Orville Browning handed over the Douglas seat to an old friend, who happened to be of the rival party. Browning rejoiced over the prospect of going home but wrote in his diary, “I am despondent, and have but little hope left for the republic.”

As a member of the Senate minority, the former colonel in the Mexican-American war, Richardson expressed great interest in military matters. In fact, Lincoln had offered a commission in the Union army that Richardson turned down. Among the issues he addressed was an alleged technique on the part of the military that enabled Republican soldiers to vote in elections, while denying the same opportunity for Democrat soldiers. Richardson also urged that the recently dismissed Gen. George B. McClellan be restored to command of Union armies.

In the Senate chamber, despite being newly elected, Richardson used his relationship to Douglas to act as a major spokesman for his party. He spoke passionately in opposition to conscription (the draft) and the policy of allowing men to buy substitutes. The latter allowed the more affluent to avoid service, while ordinary workers had no such alternative.

As senator, he considered himself the “loyal opposition,” but opposition it was to nearly everything proposed or effected by the Lincoln administration. He called for the recall of the Emancipation Proclamation and he, in essence, asked for the return of the status quo ante bellum. This meant state sovereignty and the preservation of slavery. Derided by the opposition for his positions, he responded that his loyalty was to the Constitution, which he asserted was “true patriotism.”

In the summer of 1863, with the congressional session over, he returned to Quincy. He encountered the sad situation of his wife Cornelia being desperately ill. Richardson thus curtailed almost all political activity to stay with his wife. He did oppose a so-called “peace plank” of his party that literally advocated calling off further prosecution of the war. Instead, he counseled that the way to achieve Democrats’ goals was by winning elections. They could thus repeal emancipation and produce an honorable restoration of the South, with slavery, to the Union.

When the new session of congress resumed in 1864, Richardson was absent, staying home with his fatally ill wife. Cornelia died in April, 1864, and he confessed, “The light went out of his life.” He returned to a half-hearted participation in the Senate’s affairs. With the results of Lincoln’s reelection and the Republican victory in Illinois, his Senate days were numbered and he prepared to turn over the Douglas seat to his Republican successor, Richard Yates, the recent governor of the state. So ended nearly four years of Senate service, by citizens of Quincy.

Professor Emeritus David Costigan held the position of the Aaron M. Pembleton endowed chair of history at Quincy University.