Quincy organized black regiment for Civil War

Before turning south onto Washington, D.C.'s, 14th Street, the 29th U.S. Colored Infantry, organized in Quincy, halted momentarily on New York Avenue to close ranks.

The 29th was part of the "Black Phalanx Regiments" of the 9th Corps of the Army of the Potomac. On this clear Monday morning, April 25, 1864, President Abraham Lincoln would review the 29th Illinois in parade. Although his Emancipation Proclamation freed no slaves in the Border States -- slave states that had remained loyal to the Union, dozens of Missouri slaves had fled to Quincy in late 1863 and early 1864 to join Illinois' first regiment of black soldiers.

Col. Clark E. Royce, the 29th's commanding officer, rode his mount down the length of the six companies, encouraging his soldiers to keep their lines straight and to stay in step. The men of his regiment, all but the officers black, had been sworn into service the day before. To that moment, their unit had been called the First Regiment Illinois Volunteers (Colored). They were now the 29th U.S. Colored Infantry.

President Lincoln and the 9th Corps' commanding officer, Gen. Ambrose Burnside, were on the balcony over the entrance of the Willard Hotel, a half-mile southeast of the White House. It was their vantage point for reviewing the long stream of men and horses and wheeled artillery in the 15,000-man force. The soiled, tattered flags of most units were testimony to the great battles this army had fought in six states and to the courage its men had displayed in this great Civil War.

Quincy's new 29th had not been tested so could claim neither victory nor valor. But expectations were high. The 54th Massachusetts, the Union army's first regiment of black soldiers, on July 18, 1863, fought heroically at Fort Wagner, Morris Island, S.C. Their heavy losses and courage in leading the battle dispelled the belief that blacks could not fight as well as whites.

On Col. Royce‘s command, the 29th rounded the corner of New York Avenue. Each line of men pivoted true and as straight as spokes onto 14th Street. Their freshly blackened boots, filling New York Avenue from sidewalk to sidewalk, sounded like a thousand drums beating in unison. The Quincy Daily Herald had said the 29th's boots were big enough "to trample on the rights of the South." It was no compliment. The newspaper was the voice of the Quincy area's anti-war Democrats -- Copperheads -- and had criticized Lincoln and Illinois Gov. Richard Yates for enrolling black troops. Gangs of like-minded men had attacked some of the black men on their way to Quincy to join the army.

Martin Robinson Delany of Chicago, one of the first three blacks admitted to Harvard and a trained physician, for several months had been in Quincy recruiting black men for Connecticut and Rhode Island regiments. Seeing them willing to fight for their country--and to stop other states from recruiting them, Yates in July 1863 issued an order to raise a regiment of black troops and prohibit recruitment in Illinois by other states.

Critics' voices were muted by several facts like those reported by the Quincy Whig Republican that argued for colored soldiers: each recruit counted toward the state's quota for volunteers, each could be enrolled the same as whites, could be drafted, and could substitute for whites. Each factor had the effect of reducing the number of whites who, otherwise, faced conscription. The Quincy Daily Herald, however, argued that there were factors more fundamental. On Aug. 17, 1863, the newspaper responded that "white soldiers are not entirely satisfied with the arrangement of the president ... putting negroes into the field as their equal in all respects as defenders of the flag of our country."

The Herald's was a sentiment that permeated prairie Illinois, including Lincoln's hometown of Springfield, to which the president himself responded. In a letter that he asked to be read at a Union rally in Springfield on Sept. 3, 1863, Lincoln wrote, "You say you will not fight to free negroes. Some of them seem willing to fight for you; but, no matter. Fight you, then exclusively to save the Union."

The Herald continued its assault against equality for blacks: " ... The President says in his letter that he is ‘against giving up the Union.' But he also says he is against giving up his free negro proclamation. The people know that he must give up one or the other."

The newspaper's criticism may have backfired. A few days later, the Herald reported it had learned that some of Quincy's leading Republicans had asked Washington "for authority to raise a negro regiment here."

The letter was important toward Quincy's selection as the location to organize men for the state's only Negro regiment.

In November 1863, Gov. Yates appointed Capt. John Armstrong Bross of Chicago the regiment's commanding officer. Bross arrived in Quincy a week later.

The Daily Whig mocked the complainers: "Howl Ye Copperheads! The ‘First Regiment Illinois Colored Volunteers,' by an order of Gov. Yates, is to rendezvous in Quincy. We hope the Copperheads will bear this information with becoming resignation, as it may result in their good. The colored volunteers are all Democrats, and will at once subscribe for the Herald!"

In a more serious tone, the Whig on Nov. 24 played on Lincoln's message, pointing out that even free Negroes had been "grossly wronged and insulted" by Illinois' "Black Laws" and were facing new wrongs with unequal treatment in the army. White soldiers, for example, were paid $13 a month while blacks drew $3 less and received smaller bounties for enlisting.

"The colored men have done enough already in this war," the Whig editor wrote, "to greatly heighten the esteem in which they have been held, and the sentiment is now general among loyal men that all distinctions as to pay and bounties between them and white soldiers be abolished by Congress at the earliest moment."

The Whig suggested that city government follow the lead of Galesburg and equalize the pay and bounty for black soldiers from Quincy.

Meetings of black and white Quincyans were held in late 1863 to encourage Negro enlistments. On Nov. 14, Negro citizens of Quincy met at the African Methodist Episcopal Church on Oak Street where there rose "tremendous cheers for the Constitution and the Government without slavery. ... Inasmuch as the government has thrown around us her protection, we will rally round her flag and defend her against opposition, let it come from whatever source it may."

Six men that night gave their names to become soldiers.

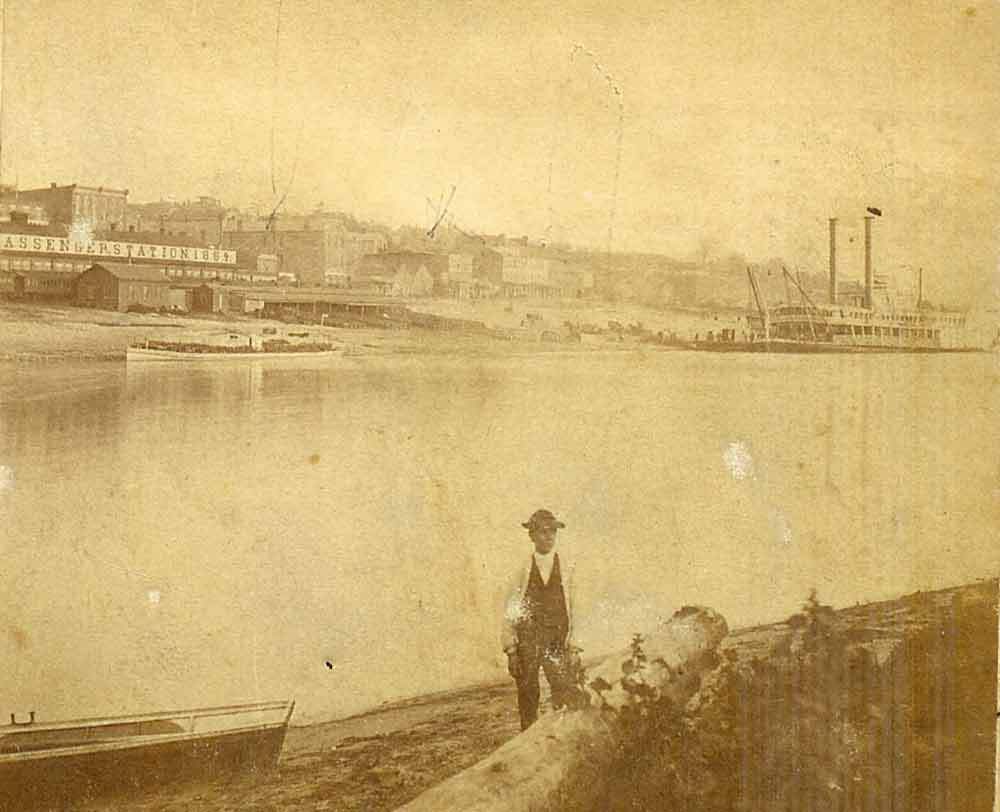

By the end of January 1864, the Quincy Herald reported that 500 Negro men were in Quincy for supply and training. Company A, though called the Quincy Company, was largely made up of fugitive slaves from Lewis, Marion, Pike, and Ralls Counties in Missouri. Many recruits brought with them wives and children to assure they would not suffer for slave masters' losses. They were housed in wooden barracks on property owned by abolitionist Dr. David Nelson, just north of Nelson's Mission Institute (east of Quincy near today's Lowe's store).

As they marched up New York Avenue, the men of the 29th could see the president, stretched taller than all the men around him. The Black Phalanx Regiments were the first African American troops Lincoln had reviewed, and he was pleased. He lifted his tall black hat from his head and tipped it toward the black soldiers as they passed. The adjutant general reported that the Quincy soldiers raised their hats and shouted, "Three cheers for the president."

The 29th fought in several battles in Lt. Genl. Ulysses S. Grant's Petersburg-Richmond Campaigns. The regiment exhibited particular bravery at the ill-fated Battle of the Crater at Petersburg, suffering 275 casualties, most of any unit. Lt. Col. Bross was one of them. His men faltered under a withering rebel fusillade. The fifth flag bearer had just fallen. Bross retrieved the flag, rallied his men, and led them forward. He was killed within a minute in the murderous fire. More men suffered the like.

Survivors continued on with Grant, were with him in the Appomattox Campaign, which ended the Civil War. The men of the Quincy's 29th were mustered out Nov. 6, 1865, at Brownsville, Texas.

Reg Ankrom is a member of the Historical Society of Quincy and Adams County and several other history-related organizations, the author of a biography of Stephen A. Douglas, and a frequent speaker on pre-Civil War history.

Sources

"Company "A" 29th Regiment U.S. Colored Infantry." http://civilwar.illinoisgenweb.org/r155/29usc-a-in.html , accessed January 23, 2014.

Hicken, Victor. Illinois in the Civil War. Urbana, Illinois: University of Illinois Press, 1966.

----------. "The Record of Illinois' Negro Soldiers in the Civil War," Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society, Springfield, Illinois: State of Illinois, Autumn 1963.

The Lincoln Institute. "Abraham Lincoln and Black Soldiers." http://www.abrahamlincolnsclassroom.org/library/newsletter.asp?ID=160&CRLI=217 , accessed January 20, 2014.

Lincoln, Abraham, to James C. Conkling, August 26, 1863, in The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, ed. Roy P. Basler. New Brunswick, New Jersey: Rutgers University Press, 1953.

Miller, Edward A. Jr. The Black Civil War Soldiers of Illinois: The Story of the Twenty-ninth U.S. Colored Infantry. Columbia, South Carolina: University of South Carolina Press, 1998.

The Quincy Daily Herald, January 29, April 16, June 2, August 17, September 4 and 7, and March 5, 1864.

The Quincy Daily Whig, October 5 and October 29, November 23 and 24, and December 5 and 29, 1863.

The Quincy Whig Republican, November 14 and 28, and December 5, 8, and 23, 1863.

Schmutz, John F., The Battle of the Crater: A Complete History. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland and Company, Inc., Publishers, 2009.

Waters, Ellen Deters, in discussion with the author, January 23, 2014.

Reg Ankrom is a member of the Historical Society, several other history-related organizations, the author of a biography of Stephen A. Douglas and a frequent speaker on pre-Civil War history.