Rev. Asa Turner builds a church in Quincy

The two-story brick Italianate home of Dr. and Mrs. Richard Eells on Jersey near Fourth Street stood in marked contrast to a primitive wood-frame structure nearby that Quincyans called "The Lord's Barn." The latter was the town's first church building, situated in the block just south of John's Square. Occupants of the two buildings would become known to Quincy history for opposing the stain and sin of slavery.

The 22 x 26-foot Lord's Barn was no more elegant than a wood shed. It was unpainted and had not a stitch of cushion or carpet inside. The church's seats were rough-hewn boards, an occasional curling splinter snagging a loose thread of the congregants' homespun. A single stove was situated near the preacher's pulpit, which rose slightly on a platform so that the Word of God could be preached from a higher place.

At the front of the church, Judge Henry H. Snow played his bass viola to lead the small congregation in hymns he chose for the three Sunday services. The honorific "judge" recognized Snow's position as probate and circuit judge. He might as easily have been called "clerk" or "treasurer" since he held nearly every other office in the county.

Perched on two poles behind the church was an oversized church bell, for which hours of needlework by the congregation's women had paid. The bell rope entered the church through a hole behind the pulpit. The bell today is installed in the south portico of the Gov. John Wood Mansion at 12th and State streets. A brass-cased clock, a treasured artifact in the collection of the Historical Society of Quincy and Adams County, was hung near the door.

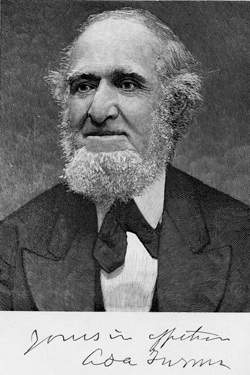

On Saturday, Dec. 1, 1830, the Rev. Asa Turner and the Rev. Cyrus L. Watson, ministers of the Illinois Home Mission Society, formed the Presbyterian Church in Quincy. Turner found "satisfactory Christian evidence" to admit 14 persons into the church that afternoon and the 15th that evening. Until the Lord's Barn -- said to be as simple as the manger of Jesus Christ -- was finished, Deacon Peter Felt continued to hold meetings of the small congregation in his cabin on the next lot over. Within three years, congregants unanimously made it the First Congregational Church, ancestor of today's Congregational Church at 12th and Maine.

The 31-year-old Rev. Turner and his 21-year-old wife Martha had moved from Massachusetts to Quincy, part of a migration of young New England ministers seeking to evangelize the West. With an unbounded religious spirit moving him, Turner earlier had convinced his father to send him to Yale College and then to Yale Theological Seminary to prepare for his calling.

A camp revival near his family's home in Templeton, Mass, first stirred the passion that would boil within him throughout his 86 years. "Father Turner," as his Quincy congregation called him, took his newfound religion into his father's home, where he initiated daily family prayers. Turner's prayers went everywhere with him, and he made home and family wherever he went.

On a trip into Iowa one midwinter Saturday night, Turner sought sleeping quarters in a small village's only tavern. While other lodgers whiled away the time playing cards and drinking intemperately, Turner rented space to sleep and immediately ascended the stairs to it. At 9 p.m. he returned, his Bible in hand.

"Gentlemen, it is my custom to have family prayers at night before retiring," he told his mirthful fellow lodgers. "If you would not object, I would like to have prayers with you."

The offer drew a scornful chorus. Glasses clinked and the betting continued.

Turner was unbothered. He read a verse from the Bible, then went to his knees and prayed. An acquaintance who told a niece the story said it seemed that "each individual soul was being carried to the throne of grace."

The glasses quieted. The cards were laid on the table. Silence enveloped the room. Turner finished his prayer, rose and returned to his quarters upstairs. Without a word, the others followed. The tavern closed early.

Asa Turner's wife, almond-eyed Martha Bull, was petite, prim and to Turner perfect. She was the daughter of a wealthy medical doctor of Hartford, Conn. At the school of Miss Catharine E. Beecher in Litchfield, Conn., she was taught by Beecher's sister Harriet Beecher Stowe. These were strong women. They were daughters of abolitionist minister Lyman Beecher and sisters of abolitionists Henry Ward Beecher and Edward Beecher, the first president of Illinois College in Jacksonville. After Stowe became famous for her novel, "Uncle Tom's Cabin, " Martha Bull proudly remembered teaching Stowe her favorite hymn. The Beechers brought Turner and Bull together in the spring of 1830. Friend George Beecher had invited Turner to study with his father Lyman Beecher in Boston.

Turner believed winning the affections of Miss Martha Bull would be a hard climb, but smitten by her as he was, he became a climber. His letters to her were long and businesslike.

"I presume by this time you will have no doubt that I feel an interest in you," he wrote in July 1830. "This has been constantly increased by our acquaintance, and I think we ought to take every opportunity to render our acquaintance more intimate."

"What God designs by this providence we know not now," he advised her. But he was quick to add, "I was glad to hear you say that you could submit to His will."

Turner then wrote for her what he called "an abstract of my history." He told her he had been a farmer but had a "notion of what a gentleman ought to be. ... Now I want my wife to take me just as I am, and make me what I ought to be. Do not shrink from the task!"

He would be "tractable," he said.

The arguments proved effective to her -- and her parents. The last of their six children, Martha Bull married Turner the next month.

Mrs. Turner knew that the salary of her husband's calling would provide scant luxury. She could not have known how scant. Her Quincy quarters were a log cabin. She didn't complain. There were cabins worse than hers, she wrote a friend. Turner wrote his mother that his new wife had become good at making butter.

With only a small salary coming from back east and with his 15 congregants in Quincy too poor to provide much, the Rev. Turner once had to sell some of his clothing to subsist. Within a year his horse died. And as insufficient as his own earnings were, Turner was known not to turn away anyone who sought his pecuniary help.

In the first year, with his financial condition carrying him toward destitution, Turner considered leaving the ministry to farm the Mississippi bottomlands he admired south of Quincy. He gave up the idea, he wrote a friend back east, because there was no one else within 80 miles to preach.

Turner committed himself fully to preaching. He once lamented that he had to preach twice on the Sabbath and on Wednesday evenings, hold prayer meetings Thursdays and conferences Saturday, and superintend the Sabbath school Sunday. He told a friend, "I can not preach in the country more than once a week." By the following year, however, he was preaching in the country twice a week. He founded more churches at which he would be required to preach, including one in Atlas and another at Pittsfield.

Lorenzo Bull, a nephew of Turner's wife, wrote that Turner could not deny a call to spread the Word. "He was accustomed to ride in all directions, preaching wherever a few could be gathered in a settler's cabin, unsparing of his own time and strength, and always ready to take a dreary ride and face swollen creeks without bridges to keep an appointment or to render a service."

After seven years in Quincy and despite pleas by John Wood that he stay, Turner moved on to Denmark, Iowa, where he founded a new church and Iowa College. He left in Quincy a spirit of brotherly love that grew from a small seed, a small church from which a vine and many branches grew.

"Almost every church in Quincy, every form of sectarian organization," wrote Quincy historian John Tillson, "is an offshoot, or, as one might say, a shingle from ‘God's Barn.'"

Under the roof of his primitive church Turner preached with fervor a love for all God's children. In coming days the import of Turner's message would create divides in the city of Quincy.

Reg Ankrom is executive director of the Historical Society. He is a member of several history-related organizations, the author of a history of Stephen A. Douglas and a frequent speaker on pre-Civil War history.

Sources

Carriel, Mary Turner. The Life of Jonathan Baldwin Turner. Urbana, Illinois: University of Illinois Press, 1961.

Deters, Ruth. The Underground Railroad Ran Through My House. Quincy, Illinois: Eleven Oaks Press, 2008.

Magoun, George Frederic. Asa Turner, A Home Missionary Patriarch and His Times. Boston: Congregational Sunday-School and Publishing Society, 1889.

Quincy Daily Whig. June 23, 1909.

"Quincy Historical Papers of 1912." Transactions of the Illinois Historical Society for the Year 1915. Springfield, Illinois: Illinois State Journal Company, State Printers, 1916.

Tillson, John. History of Quincy. In William H. Collins and Cicero F. Perry, Past and Present of the City of Quincy and Adams County, Illinois. Chicago: The S. J. Clarke Publishing Co., 1905.

Yeager, Iver F. Julian M. Sturtevant, 1805-1886, President of Illinois College, Ardent Churchman, Reflective Author. Jacksonville, Illinois: The Trustees of Illinois College, 1999.