'Ruined' woman tragically takes law in her own hands

A young woman from near Camp Point tried to gain justice in two states and finally resorted to serving it out herself. However, there is a price to pay for taking the law into your own hands. Lillie Booth became the second casualty of her actions.

The story involves a promise to wed given to Booth by Dan Price, also of Adams County, where their two families knew each other and the pair grew up near Camp Point. They became engaged after meeting four or five times, and Booth, opting not to wait for the wedding ceremony, soon found herself pregnant without a wedding ring. She journeyed or was sent away to bear the child, who was born in Missoula, Mont. Booth was a ruined womn.

By April 1890, she was back in Illinois and talking about suing her fiance. By this time, Price had business interests in Kansas, where he and his brother-in-law offered money to lend. Apparently all was well, at least with the business. However, Price declined to admit Booth's child was his and shoulder the burden of supporting it.

In Illinois at the time, laws tended to offer more protection to the men involved in what were called bastardy cases, than they offered help to the mothers. Price returned to Illinois and remained for four months, offering an opportunity for Booth to file suit. She declined, knowing she had a better chance for monetary support under Kansas laws.

Eventually, Price returned to Kansas, and Booth's lawyers followed and filed suit. The Kansas papers expressed the opinion that Illinois' dirty linen should stay in Illinois.

The case, which was heard behind closed doors, related that Price had courted Booth beginning in February 1889. When she became pregnant, he declined to marry her, denying responsibility. Under family pressure, he signed an agreement saying that if the child were born fully formed after March 1, 1890, he would marry Booth. The child was born the last day of February, voiding the agreement and allowing the judge to dismiss the suit for maintenance for the child. On Sept. 19, 1890, the Salina Herald quoted the judge as saying, "The whole of her (Lillie Booth) testimony bore the impress of truth." Still the child was born three weeks early if the dates in her story were true.

It was all to come to a conclusion in Quincy in October 1890, but many things remained unclear. The Daily Journal's headline on Oct. 19, 1890, reflected that uncertainty, "The Booth-Price Tragedy, A Complete and Probably Reliable Report of the Murder of Dan G. Price." This caveat was given because the multitude of conflicting witness statements made it hard to untangle the sequence of events.

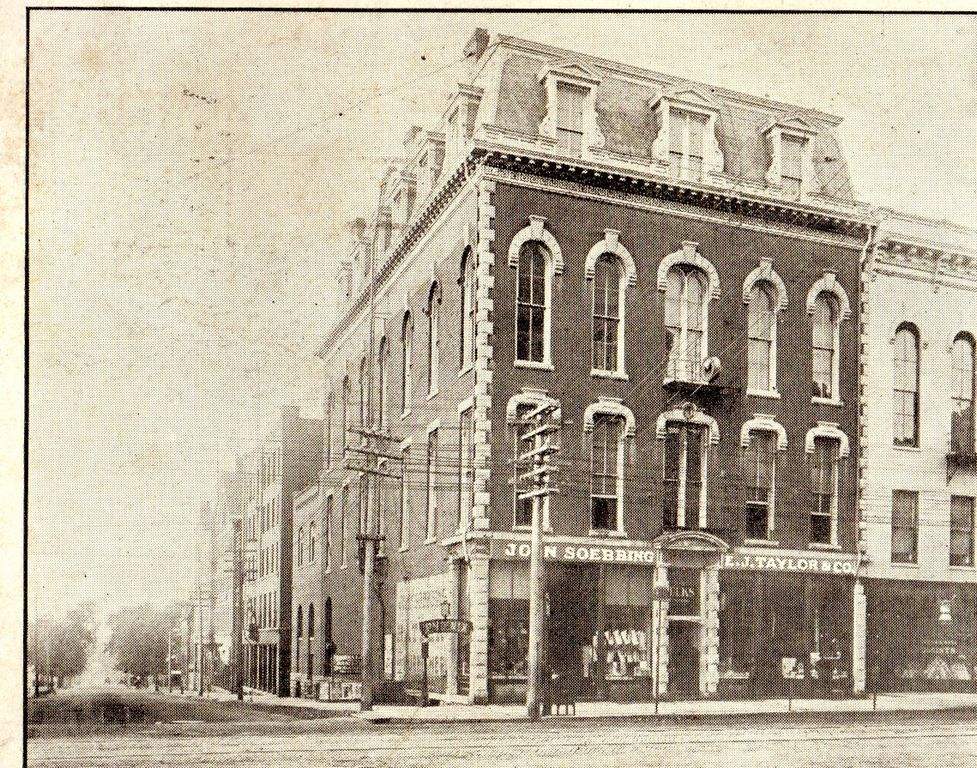

Just after noon on Oct. 18, 1890, Price and his brother Seymour Price were walking north up Sixth Street from Maine headed toward the Gatz tailor shop, where a new suit awaited Dan. Booth approached them from behind with a .38-caliber American Bulldog. She walked rapidly until within a few feet of the unnoticing men and pulled the trigger, shooting Dan. He staggered into Mr. Locke's wallpaper shop, where he pulled out a .38-caliber Smith and Wesson pistol and returned to the street. His brother had lunged at and caught Booth's arm, which he twisted behind her as she tried to fire again. Dan Price fired once, missed and tried to get off another shot, which misfired.

At almost the same instant as Price tried to fire his second shot, Booth's gun went off in the struggle with Seymour, striking her in the back on a rib near her spine. Price returned to the store, where he collapsed and was placed on a cot. Booth was bundled into a hack and sent to be treated by Dr. Lee at the corner of Twelfth and Jersey streets, where it was erroneously determined to be a nonfatal wound. Booth was sent on to St. Mary Hospital.

Dan Price was judged to be mortally wounded, and his cot was carried through the streets from Sixth and Hampshire to Blessing Hospital. He called for Mr. Govert, his attorney, and made a statement saying he was not responsible for ruining Booth. Price especially wanted his mother to know. He was pronounced dead a little after 4 p.m.

Meanwhile, Seymour Price had sworn out a warrant for Booth and a deputy had been dispatched to guard her hospital room. Booth died the next day just before 7 a.m. Price was buried in Burton, and Booth was buried in the family cemetery near Ursa.

A Booth inquest was convened Oct. 21, to a full house and deputies carefully disarming the many relatives from both the Price and Booth families. Stories from various witnesses were hard to reconcile because both of the guns had misfired at least once, and there were bullets loaded in each pistol that had distinctive flat-nosed tips. Price's gun had one bullet fired, and one misfire and four unfired shells. Booth's gun had one empty chamber, a misfired bullet, another empty chamber, and the rest full of unfired shells. Booth's wound showed powder burns from close contact, and directly after the shooting her dress was smoldering at the entry point.

Booth's death was determined to be "accidental discharge of a pistol held in her own hands," according a Quincy Daily Whig story on Oct. 21, 1890. A second inquest found that Dan Price "came to his death by a pistol shot fired by the hands of Lillie E. Booth." (Quincy Daily Journal, November 9, 1890.) The family of Dan Price in the paper just quoted, published its side of the story, in an article called "Justice," exonerating Price. His last words were a request to tell his mother that he did not ruin that woman.

Beth Lane is the author of "Lies Told Under Oath," the story of the 1912 Pfanschmidt murders near Payson. She is the former executive director of the Historical Society of Quincy and Adams County.

Sources:

"Ain't It Strange," Quincy Daily Whig, Sept. 21, 1890.

"Avenge Honor," Quincy Daily Herald, Oct. 19, 1890.

"D G Price Killed," Salina Semi-Weekly Journal, Oct. 24, 1890.

"Double Tragedy," Quincy Daily Whig, Oct. 19, 1890.

"Eyewitness," Quincy Daily Journal, Oct. 20, 1890.

"Isn't it Strange," Quincy Daily Whig, Oct. 21, 1890.

"Lillie E Booth is Dead," Quincy Daily Journal, Oct. 20, 1890.

"Miss Lillie Booth Dead," Chicago Tribune, Oct. 20, 1890.

"The Booth-Price Tragedy," Quincy Daily Journal, Oct. 19, 1890.

"The Case Against D G Price," Salina Daily Republican, Sept. 16, 1890.

"The Inquest," Quincy Daily Whig, Oct. 21, 1890.

"The Linen Washed," Salina Herald, Sept. 19, 1890.