Socialist accused of violating espionage act tried twice

Floyd Dell was born in Barry in 1887 to an oft-unemployed Civil War veteran father and a former teacher. The Dell family lived a tenuous economic existence. Having lived on potato soup one winter, the 6-year-old Floyd realized the family was poor. In 1899, the Dells left Barry for Quincy, joining older children who were working there.

Leaving Barry was an important event in Floyd's life. He flourished at Franklin School, where he was a member of the literary society. In "Homecoming," his autobiography, Dell wrote: "After school there was the library, a grey stone building on the corner Square, with young women behind the counter. ... And, though it was against the rules, I was allowed by these sympathetic guardians of the books to go behind the counter, direct to the shelves. ..."

Making ends meets was a never-ending struggle for the Dell family. So it is understandable, as Floyd explained in his autobiography, that he would stop and listen to a man speaking to a small crowd on the plight of the working class.

"Afterward I talked to him; he was a (Quincy) street-sweeper. And my long-slumbering Socialism woke up. Of course I was a Socialist!" Invited, he attended a socialist meeting in the backroom of a local jewelry store.

He later wrote, "My life seemed now to have some meaning, to be whole." He added: "I could accept my destiny as a working man with good grace, for it was by my class that this whole sham civilization would be destroyed, and a new one erected all over the world."

Late in the summer of 1903, the Dell family moved to Davenport, Iowa, where Floyd chose to not return to school but took a factory job. Floyd continued his socialist bent. But in his autobiography, Dell recalled that an older and committed socialist advised him "to not pre-judge life, but to take it as it came and see it as it was." He also encouraged him to use his mind to make a living. With that advice the 17-year-old Floyd landed a job as a reporter with the Davenport Times, a move that changed his life.

In 1909, the Chicago Evening Post offered and Dell accepted a job as an editor and chief contributor to its weekly supplement, the Friday Literary Review. In the Windy City, he became a well-known critic and leader in Chicago's literary renaissance and came to know and promote the work of some of the city's budding writers such as Carl Sandburg, Edgar Lee Masters and Theodore Dreiser.

In 1913, Dell took a position in New York City as an associate editor of the radical magazine, The Masses. Edited by Max Eastman, The Masses was a cooperative effort of artists and writers who wanted a magazine where they could write, draw and publish what they pleased. The magazine's only policy was complete freedom of expression for its editors. In its outlook, the magazine's politics were socialist.

The first two decades of the 20th century were the high-water mark of socialism and the American Socialist Party. In the 1912 presidential election, the Socialist candidate, Eugene Debs, garnered nearly a million votes. The Socialist Party elected a number of mayors, legislators, and congressmen. Locally, Socialist Henry Rosendale won the fourth ward alderman seat in the 1912 municipal election.

As it became evident that the United States would eventually be dragged into the Great War, Eugene Debs called the war a capitalist fight. Initially, the American Socialist Party opposed all war, the exception being the ongoing battle of the working class against the capitalists.

Nine days after entering the Great War, the Wilson administration's Espionage Act became federal law. The act specified that it was a crime to interfere with the armed forces prosecution of the war or to aid the nation's enemies. It spelled out that anyone found guilty of obstructing recruiting, causing insubordination, or disloyalty, or refusal of duty in the armed forces was subject to a $10,000 fine and a 20-year prison sentence.

Congress, however, refused President Woodrow Wilson's request for press censorship, but it gave the executive branch the right to block distribution of printed materials. The Post Office could impound any mail it believed interfered with the operation or success of the armed forces or aided its enemies.

While making the world safe for democracy, the Wilson administration curtailed freedom of speech at home.

The Masses, which had taken an antiwar stance, was deemed by the postmaster general to be undeliverable. He claimed that the magazine's August 1917 issue intended to interfere with the operation or success of the armed forces.

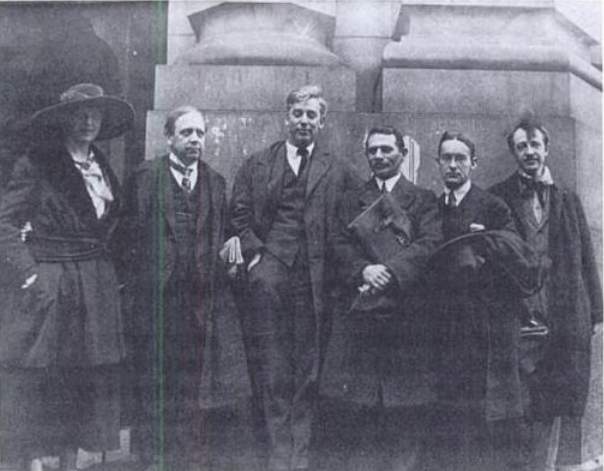

The Justice Department indicted Eastman, Dell and five others in November 1917. Covering the trial for The Liberator, Dell wrote that he and his co-defendants were charged "for conspiring to violate the Espionage Act -- conspiring to promote insubordination and mutiny in the military and naval forces of the United States and to obstruct recruiting and enlistment to the injury of the service."

Four cartoons and three editorials from the magazine's August issue were cited in the indictment.

Dell's piece advocating for conscientious objectors was one. He wrote: "There are some laws that the individual feels he cannot obey, and he will suffer any punishment, even that of death, rather than recognize them as having authority over him. This fundamental stubbornness of the free soul, against which all the powers of the State are helpless, constitutes a conscientious objection, whatever its source may be in political and social opinion."

The trial began April 15, 1918, and lasted nine days. In The Liberator, Dell explained that the defense agreed that the accused "published a radical magazine in which unpopular views were expressed." However, Dell wrote that the question before the jury was whether "the defendants conspire to violate the Espionage Law, or were they merely exercising their lawful right to the free expression of opinion?"

After deliberating for three days, the jury failed to reach a decision, and a mistrial was declared. A second trial took place Oct. 1, 1919, and again the jury failed to deliver a verdict. Floyd Dell and his co-defendants were free.

Phil Reyburn is a retired field representative for the Social Security Administration. He authored "Clear the Track: A History of the Eighty-ninth Illinois Volunteer Infantry, The Railroad Regiment" and co-edited " ‘Jottings from Dixie:' The Civil War Dispatches of Sergeant Major Stephen F. Fleharty, U.S.A."

Sources:

Baran, Madeleine. "A Brief History of The Masses." The Brooklyn Rail, April 1, 2003.

"The Biographic Dictionary of Iowa." Floyd Dell. Chicago Tribune. February 25, 1996.

Gorton, Carruth. "The Encyclopedia of American Facts and Dates." New York: Thomas Y. Crowell Co., 1956.

Draper, Theodore. "The Roots of American Communism." New York: The Viking Press, 1957.

Dell, Floyd. "Homecoming, An Autobiography." New York: Farrar & Rinehart, 1933.

Dell, Floyd. "The Story of the Trial (Part I)." The Liberator, June 1918 and "The Masses Trial as Told by a Defendant, Part II." The Liberator, July 1918.

Hart, John E. "Floyd Dell." New York: Twayne Publishers Inc., 1971.

The Herald-Whig. July 30, 1969; Sec. B, p. 14.

Morris, Richard B., editor, "Encyclopedia of American History." New York: Harper & Brothers Publishers, 1953.

Morrison, Samuel Eliot. "The Oxford History of the American People." New York: Oxford University Press, 1965.

The Quincy Daily Herald. Feb. 7, 1903; Nov. 20, 1917; Nov. 23, 1917; April 27, 1918.

The Quincy Daily Whig. Jan. 13, 1901.