Scopes “Monkey” Trial Polarized Local Public

The

1920s brought profound changes to the United States: traditional values,

beliefs, and ideas clashed with the modern world that novelist F. Scott

Fitzgerald called the “Jazz Age.” These

societal shifts divided public opinion and lifestyles in conservative midwestern

cities like Quincy, where religion had been a dominant force. The Gem City had

nearly 60 churches and many allied religious groups, including the “Ben-Hur

Club” named for the era’s best selling Christian book and the 1925 silent

movie.

World War I had disillusioned many people in their belief that God created humans in a divine image. The notion that science could explain life as well as religious orthodoxy captivated the American scene. Scientists had recently discovered antibiotics and developed vaccines against diphtheria, tuberculosis, and the one that halted the world-wide Great Influenza Epidemic—which in Adams County had claimed about 500 lives and sickened several thousand more.

A new literary genre called “science fiction” dazzled public imagination. Quincy papers serialized one of these first stories, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s “The Lost World,” and the movie version played to packed audiences at Quincy’s Orpheum, Empire, and Washington Square Theaters.

Many local citizens, weary of war and Victorian morality, overlooked illegal alcohol use, gambling, and the brazen behavior of “flappers” and “zoot-suiters.” Clergymen like Rev. Celian Ufford of Quincy’s Unitarian Church delivered sermons and gave dramatic readings of plays, such as Eugene O’Neil’s “Emperor Jones,” which mirrored the new scientific understanding of mankind’s animal origins.

On March 13, 1925, Tennessee passed the Butler Act, which prohibited the teaching of human evolution in public schools and sanctioned only the literal interpretation of creation in the Biblical book of Genesis. This law silenced the scientific theory proposed in Charles Darwin’s 1859 book “The Origin of Species By Means of Natural Selection,” which documented evidence that all life evolved over millions of years, and humans had descended from a species of primates.

A group of businessmen in Dayton, Tennessee, eager to boost the town’s struggling economy, conspired to “put Dayton on the map” by challenging the law in court. They secured high school science teacher John T. Scopes’ complicity with his admission that he had taught Darwinian evolution from a state-mandated book. Officials arrested Scopes, and soon the two most prominent lawyers in the country, Clarence Darrow for the defense and William Jennings Bryan for the prosecution, took sides in the case. Bryan had visited Quincy in September 1919 and given a speech to several thousand people endorsing another conservative cause: the newly-ratified 18th Amendment establishing Prohibition.

On July 10, 1925 testimony began in what Journalist H. L Mencken dubbed the “Scopes Monkey Trial,” and it became the 20th century’s most famous legal battle.

The Quincy Daily Journal published views of several prominent local citizens about the upcoming trial on May 31, 1925. Dr. William H. Baker, a well-known physician, and Charles Cottrell, Quincy postmaster, both strongly supported the scientific idea of evolution. Cottrell said, “I believe the expulsion of Scopes will be classified with Salem Witchcraft.” Illinois State Bank president William J. Singleton said he did not spring from monkeys, but that God had made him distinct from animals.

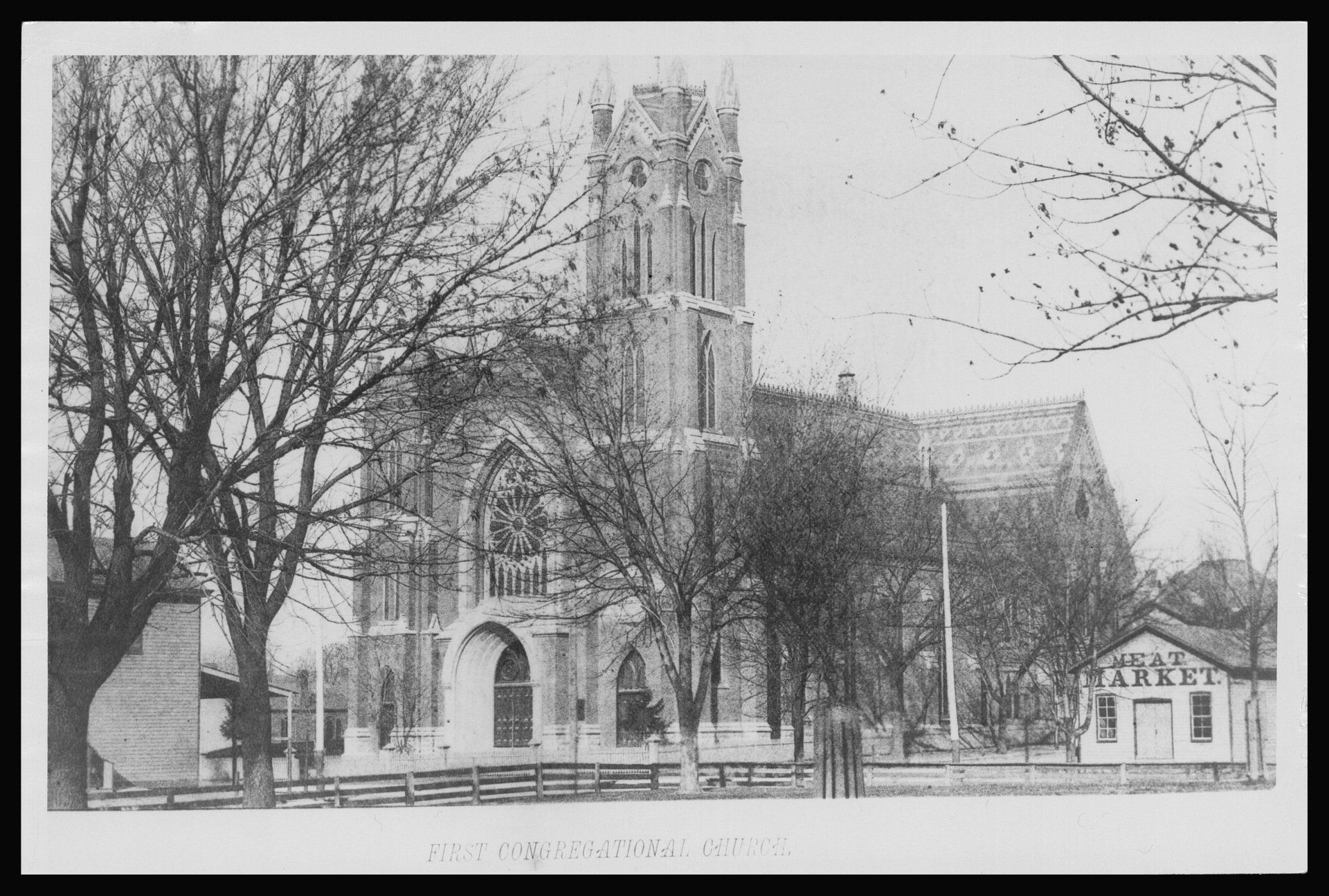

Harold L. Lummis, one of Quincy’s leading clergymen and a Sunday school teacher at the Methodist Episcopal Church, stated: “The only trouble with the theory of evolution, as I told the pastor, is that it is true.” Rev. Harry L. Meyer, pastor of the First Congregational Church, cautiously broached the subject. “The whole matter of evolution should be considered as the scientists’ understanding of the way God works in the world.”

Roman Catholics held the most conservative views about evolution. Rev. Ferdinand Grunen, president of Quincy College, said, “There can exist no conflict between scientific and revealed truth, because all truth is one, coming from one source and no other—God.” The Franciscan priest concluded, “The whole trial impresses me as a huge joke.”

Local papers and the new medium of radio provided wide coverage of the trial. An editorial in the June 15, 1925, Quincy Daily Journal noted obstacles in the case: “[Scopes] peers some of whom have no objection to a Sunday game of poker, but who would be shocked to see the Sunday paper laid atop the family Bible are trying to harmonize Darwin and Genesis. It will be wasted effort.”

After an eight-day trial, jurors took only nine minutes to find Scopes guilty of teaching evolution, and the judge fined him $100 (equal to about $1,300 today). Soon after the decision, Loren H. Wittmer, a Rockport, Illinois, native with ties to Quincy, filed a federal lawsuit challenging the verdict. An Internal Revenue Service clerk in Washington D. C., Wittmer had studied at Gem City Business College 20 years earlier and become an avowed atheist while in Quincy. In 1922 he ran for Congress in Illinois’ 20th district. He lost both his congressional bid and this lawsuit.

Although the prosecution prevailed in the Scopes Trial, the case gave evolution public prominence. Some religious leaders acknowledged that science and scripture approached the question of human origin from different perspectives. Clergymen like Rev. Harry L. Meyer of Quincy’s Congregational Church, who had before been more tentative, endorsed not only evolution but the ideas of Sigmund Freud—who, like Darwin, aligned human nature closely with animal instinct and heredity. In a speech to the Unitarian Church’s Layman's League, reprinted in the May 17, 1925, Quincy Daily Journal, Meyer, stated: “Quincy is full of men who quit thinking ten years ago...Sigmund Freud through his work in psychoanalysis has done work as great as Charles Darwin.”

Local book reviews lauded Dr. Horatio Hackett Newman’s “The Gist of Evolution” and the Free Public Library acquired volumes about the scientific method and the now widely-accepted theory of evolution. Over the objections of a few outspoken fundamentalists, Quincy Public Schools continued teaching Darwin’s theory and presenting factual evidence for man’s evolutionary ascent.

Sources

“Celian Ufford to Read ‘Emperor Jones.’” Quincy Daily Herald , Feb. 8, 1924, 4.

Darwin, Charles. The Origin of Species By Means of Natural Selection . London: John Murray Publishing House, 1859.

Larson, Edward J. Summer for the Gods: The Scopes Trial and America’s Continuing Debate Over Science and Religion. New York: Basic Books, 1997.

“Let’s See the Monster.” Quincy Daily Journal , June 15, 1925, 6.

“Pike County Man in Evolution War.” Quincy Daily Journal , July 23, 1925, 1.

“Psycho-Analysis Subject of Interesting Paper Read by Rev. Meyer Before League.” Quincy Daily Journal, May 17, 1925, 14.

“Quincyans Expressing Views on Scopes Trial, Declare it to be Nonsensical Business.” Quincy Daily Journal , May 31, 1925, 3.