Voting By Mail in 1864

The

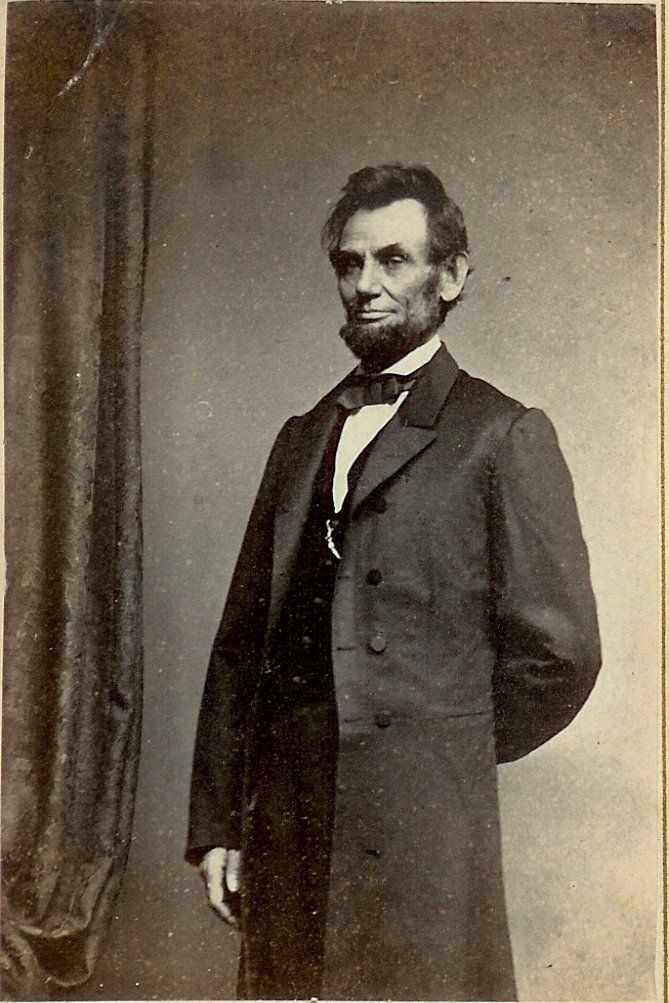

election of 1864, in which President Abraham Lincoln sought a second term,

prompted a debate about voting by mail, seditious conspiracies, disinformation,

and vote tampering. Our nation’s present controversies are not unprecedented.

As late as August 23, 1864 Lincoln expected that the voters would reject him. He required, on that date, members of his cabinet to pledge that each would support a new president and “so cooperate with the Government President elect, as to save the Union between the Election and the inauguration; as he will have secured his election on such ground that he cannot possibly save it afterwards."

Throughout his first term, Lincoln had fought not only the military war against Confederate armies, but also Northern Democrats and members of his own Republican party. Some Democrats, called Copperheads, demanded immediate peace with the South; a separate bloc of the party supported the war, but wanted Lincoln removed. A faction of Republicans, called Radicals, wanted immediate abolition of slavery and the promise of future vengeance against the South. One of Lincoln’s former cabinet members, Treasury Secretary Salmon P. Chase, had been, since 1863, exploring a challenge to Lincoln’s re-nomination.

Union military success was uncertain as late as the summer of 1863. The battle of Gettysburg on July 1--3 stopped Gen. Robert E. Lee’s invasion of northern states. On July 4, troops commanded by Gen. Ulysses S. Grant captured the Confederate fortress at Vicksburg, opening the Mississippi river to Union commerce. Gen. William T. Sherman did not capture Atlanta until September, 1864 and did not complete his March to the Sea through Georgia until December 22.

Quincy historian Carl Landrum, a century after the 1864 election, wrote of Adams County attitudes, “Many wanted an end to the war, and were willing to call it quits with an easy settlement for the South.” Landrum found in local newspapers reports of “secret organizations… part of a movement organized in the Mid-West to aid the southern army in the event it succeeded in getting this far north.” There were reports of “treasonable shouts” of support for the Confederacy in such rural Adams county towns as Stone’s Prairie (today’s Plainville, Illinois).

The war had separated soldiers and sailors from the communities in which they voted. Whether those men could vote, and whether they would support Lincoln’s conduct of the war, were urgent questions for both political parties. Moreover, Congress had established a controversial conscription system, which allowed wealthier men to avoid service by paying a substitution fee, to supplement voluntary enlistments.

The Democratic candidate for president was Gen. George B. McClelland, whom Lincoln had appointed and then removed as General-in-Chief, yet still considered popular among soldiers. McClellan pursued his political campaign while remaining an active army general.

Political leaders speculated on the ramifications of these uncertainties. Voting by mail was controversial. One scholar, Jonathan W. White, has written that leaders in both parties “knew that the soldiers' votes were crucial to winning the election and that ‘hard work must be done’ to secure them…. Consequently, Democrats from across the nation appealed to their party machinery in New York, while Republicans petitioned the federal government for support in turning out the army vote.” However, only white military men could vote; the thousands of Black soldiers, while risking their lives, were excluded from the franchise until ratification of the 15th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution in 1870.

In Quincy, questions arose about the integrity of the coming election. Landrum wrote about the concern of the Quincy Daily Whig, which had endorsed Lincoln, about “fraud at the ballot box” and its plea for vigilance until the polls closed. Adams county voters encountered also a 19th century version of disinformation: German-language handbills falsely warned of “another draft anticipated, one million men wanted, no substitutions allowed”. The county adjutant general, in charge of the local draft, said the statement was untrue.

In 1864 state law, not federal, controlled voting rights. States such as Iowa, Wisconsin, and New York allowed men serving in the military to vote by absentee mail ballot. Illinois, however, did not extend that privilege until 1865; Adams County servicemen could vote in 1864 only if they returned to their communities. On February 21, 1863, the Whig criticized the “Copperhead Democrats” controlling the Illinois legislature (presumably opposed to Lincoln’s re-election) for its refusal to enact a law permitting military absentee voting. On October 31, the Whig deplored “the Copperhead revilers [who] oppose [Lincoln] on the shallow plea that they can lawfully embarrass him as a citizen.”

For Illinois men, and others serving in his forces, Gen. Sherman allowed voting furloughs. On November 8, Lincoln won the election, carrying Illinois and Adams County. In the Electoral College, he lost only Kentucky and Delaware. The military, in this first U.S. election allowing mail voting, had strongly supported him.

Lincoln had never considered delaying or suspending the election. As historian Larry T. Balsamo wrote, two days after his victory, Lincoln told a visiting group, "we cannot have free government without elections; and if the rebellion could force us to forgo, or postpone a national election, it might fairly claim to have already conquered and ruined us."

Sources:

Balsamo, Larry T., “‘We Cannot Have Free Government without Elections’: Abraham Lincoln and the Election of 1864,” Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society 94 ( Summer, 2001): 181-199.

“The Generation of ‘Lily Livers. ’” Quincy Daily Whig , February 7, 1863, 2.

“Jim Green in Quincy-His Loyalty.” Quincy Daily Whig , October 31, 1863, 2.

Landrum, Carl, “Election century ago also caused a flurry.” Quincy Herald Whig , November 1, 1964.

“No

Chance for Soldiers.”

Quincy Daily Whig

,

February 21, 1863, 3.

White,

Jonathan W., “

Canvassing

the Troops: the Federal Government and the Soldiers' Right to Vote

.”

Civil War History

(September,

2004): 291—317.