Suffragette Sculptor Adelaide Johnson

Adelaide Johnson was an artist who studied design in St. Louis, ran a business based in Chicago and London, traveled to Italy to study sculpture, and carved a famous but controversial seven-ton piece of art currently displayed in the Rotunda at the U. S. Capitol in Washington D. C. Her beginnings were much humbler than her achievements.

Sarah Adeline Johnson was born in 1859 on a farm near Plymouth Illinois, in Hancock County. She changed her name to Adelaide and even changed the record of the year she was born to 1847. When she died in 1955, the Quincy Herald Whig obituary was titled, Noted Sculptress Who Died at 108 Plymouth Native . Her father, Christopher Johnson, came to Illinois from Indiana when he was 19. He bought 40 acres in Hancock County. Her mother, Martha E. Huff, was originally from Tennessee. Both her parents were widowed with children when they married in December, 1858. Their combined family grew to include six children.

The Johnson family farm was about 3 ½ miles west of Plymouth. Like other children of that era, Adelaide attended classes in a one-room school house. Even as a child she was artistic. She later remembered her family was never poor and described her father as poetic and her mother as artistic, which was unusual for a large family living on a small farm in west central Illinois. Nevertheless, she was taught all the skills necessary for farm life in the mid-19th century. By the time she was 16, her parents recognized her artistic talent and sent her to live with an older step-brother to attend the St. Louis School of Design. There she studied art and excelled at wood carving. Adelaide graduated in 1879, moved to Chicago and opened a design business.

Three years later she fell down an open and unattended elevator shaft and broke her hip. She received a $15,000 settlement which would amount to over $400,000 in today’s dollars. Adelaide used that money to travel and study in Germany and Italy. The Quincy Daily Journal reported in 1887 that she received a commission to do busts of both the deceased former Senator from Illinois, General John Logan, and Mrs. Logan. Throughout her career, the Quincy Daily Whig reported her travels, her studies, and her completed work in various short news items.

From the beginning of her professional life, Adelaide was influenced by women who were working to improve education and procure the vote known as suffragettes. In 1890 Adelaide became a director of the WIMODAUGHSIS Club in Washington D. C. The letters stand for a combination of wives, mothers, daughters, and sisters. According to the November 13th Quincy Daily Journal their purpose was to promote “the physical culture of women and their education in science, art and literature.”

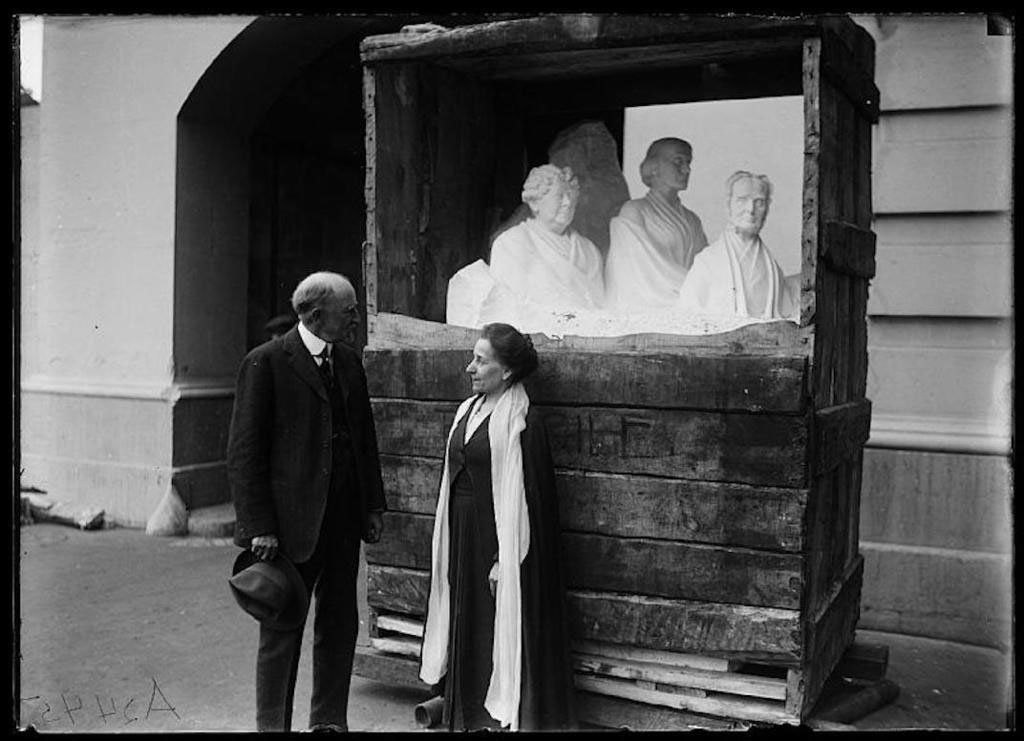

Adelaide Johnson was most famous for her sculptures of noted 19th century women, Susan B. Anthony, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and Lucretia Mott, who in 1869 were among the founders of the National Women’s Suffrage Association. This organization campaigned for women’s rights, particularly the right to vote. Adelaide eventually did nine busts of Anthony one of which was displayed with portrait busts of Stanton and Mott at the Chicago World’s Fair in 1893.

Johnson’s most famous work was commissioned by the National Women’s Party, which was founded in 1913. Their goal was to procure women’s right to vote on the national level, rather than state-by-state as the other women’s suffrage associations did. They commissioned Adelaide to carve a marble bust of the same three famous suffragettes, Susan B. Anthony, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and Lucretia Mott. With the ratification of the 19th amendment in 1920 and the long fight for women’s right to vote finally over, a celebration was planned for Washington D. C. In 1921, seventy women’s groups met at the Capitol for the unveiling of the portrait monument of the three founders of the movement. At that time there were fifty-six statues in the capitol, only one of which was a woman--- Frances Willard of Illinois. The Johnson sculpture weighed more than seven tons and was carved in Italy from Carrara marble. It was based on the individual portrait busts Johnson had made of the three women for the Chicago World’s Fair. She deliberately left it unfinished to signify that the work for women’s equality was not done. When presented, the statue had a gilt lettering inscription which read, “Woman first denied a soul, then called mindless, now arisen, declaring herself an entity to be reckoned.” Unfortunately, the work was controversial and not universally admired. Various women’s groups boycotted the ceremony as they did not like the statue or the choice of the artist who created it. After the presentation, Congress had the inscription removed and then moved the sculpture to the Crypt of the Capitol, which at that time was a storage facility.

Throughout her lifetime, Adelaide’s Plymouth and Hancock County friends stayed in touch. Any visit by them to the sculptor was noted in the paper, as was Adelaide’s 1925 visit home with her brother. The October 2, 1925 Quincy Daily Herald said, “Her parents are buried in Rosemont Cemetery, and she will always feel an interest in Plymouth and community.”

During her later years, Adelaide Johnson lived in obscurity in Washington D. C. When she died in 1955, her sculpture was still in the Crypt of the Capitol. Several times during the years, Congress was asked to move the portrait monument but refused. They said the monument was ugly and too big to move. In 1963, the Crypt was opened to visitors and the sculpture was visible after forty-two years in storage. On the 75th anniversary of the 19th Amendment in 1995, several women’s groups asked once again that the monument be moved, and again Congress refused. They said it was too big and too expensive to move. Money was raised privately, and the portrait monument was moved to the Rotunda in 1997, seventy-six years after it was given to the Capitol.

Sources

Boissoneault, Lorraine. “The Suffragette Statue Trapped in a Broom Closet for 75 Years.” Smithsonian Magazine , May 12, 2017.

Cox, Mark. “Adelaide Johnson was Hancock County’s Gift to the world of sculpture.” Daily Gate City, February 3, 2021.

“National Women’s Party Plans for Triumphal Celebration at Capital.” Quincy Daily Herald , August 19, 1920, 3.

“News and Notions.” Quincy Daily Journal , June 29, 1887, 2.

“Noted Sculptress Who Died at 108 Plymouth Native.” Quincy Herald Whig , November 16, 1955, 18.

“Plymouth Has Noted Guest.” Quincy Daily Herald , October 2, 1925, 13.

Suffrage 2020 Illinois: The Fight For The Vote In Illinois. https://suffrage2020illinois.org/2020/07/27/scultor-adelaide-johnson-from-illinois.

“WIMODAUGHSIS.” Quincy Daily Journal , November 13, 1890, 1.