The Wolfs of Quincy

Imagine prominent Quincyan Paul Wolf’s distress when at 10 p.m. August 20, 1918, he opened the oak double front doors at posh 1214 Park Place to find a United States Marshall proffering a federal warrant for his arrest for “conspiracy to defraud the United States government.”

Having been out of town that day, Wolf was unaware that Deputy United States Marshall J. Ross Moore had earlier arrested his father Fred Wolf Sr., and his brother Fred at Wolf Manufacturing Industries. Fred Wolf Sr.’s son in law, John L. Flynn, of the J. J. Flynn Bottling Company, had earlier paid each man’s $10,000 bail and obtained their release.

The August 21, 1918 Quincy Daily Journal reported, “The arrest of the Wolfs created a sensation when it became known through ‘ The Journal extra’…that they had been taken to the office of Commissioner Martindale. “The prominence of the family in commercial, social and church matters make it appear almost incredulous,” the newspaper wrote. Both Wolf sons had married into the “Catholic society circles,” as the Quincy Daily Journal reported regarding the sons’ weddings.

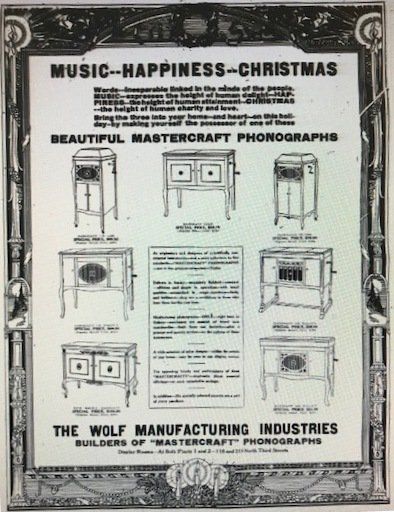

Wolf Manufacturing Industries, run by Fred Sr. and family, had been filling government contracts since 1917. Before the war office contract, the company employed forty men. By 1918, the company held a $1,800,000.00 leather goods contract with the army and employed about two hundred people. The payroll was $4000 a week.

A week before the August 20, 1918 arrests, the Quincy Daily Journal reported that a supervisor at Wolf Manufacturing told a government official “work was being sent out there which had been rejected and he did not care to assume responsibility any longer, as he himself would be liable to indictment to defraud if it were discovered that these goods had been shipped out under his supervision.”

Details of these alleged machinations came out at trail, as did the Wolfs’ counter to the accusations. At his arrest, the elder Wolf said, “This is nothing more than malice…and if rejected goods were sent to fill orders, we know nothing of it and can say that if any were shipped, they were placed in the cases without our knowledge. They must have been put in by persons wanting to do us harm.”

On February 22, 1919, a grand jury of the United States district court in Springfield heard the testimony of over fifty witnesses. Fred Wolf Sr. and Paul Wolf were indicted for conspiracy to defraud the government. Fred Wolf Jr. was not indicted. After paying $5000 bail, the Wolfs returned home. Wolfs’ lead attorney Henry Converse entered a motion to quash the indictments, but Judge Louis Fitzhenry denied the motion. A Springfield, Illinois Federal Court trial was set for June 2, 1919.

The trial began September 4, 1919 in United States Federal Court in Springfield with Judge Fitzhenry presiding. There was damning evidence, including that the Wolfs directed employees to mix rejected products with approved items and to cover rejected markings. Witnesses said Paul Wolf stole and used the inspector’s approval stamp. One inspector testified that locking up rejected goods did not keep them safe from the Wolfs. The same inspector learned to keep all stamps in his pocket. Inspector Nichols testified that he created his own private rejection mark so he could thwart the Wolfs’ scheme.

The Wolfs were found guilty. They were sentenced to Leavenworth Prison in Kansas. Fred, 70, was sentenced to one year and Paul Wolf to two years and and fined $10,000 and $5000, respectively. There was a stay on carrying out the sentences while the lawyers prepared an appeal to the U.S. Court of Appeals. But that court upheld the lower court’s decision and the Wolfs were left with one more option before they went to prison— application to the U.S. Supreme Court for a writ of certiorari. The United States Supreme Court refused the writ. Next was an appeal to President Harding. As was the policy, President Harding refused to hear it until men started their prison terms.

Upon delivery of the denial, April 18, 1922, The Quincy Daily Herald , printed a verbatim, multi-column letter from Paul, telling the Wolf side of the allegations, stating they had suffered financially, personally, and socially. They contended that the government supplied inferior materials which led to inferior product output, and thus rejected products. The Wolfs insisted the government was not “out any money” in the situation and that anti-German sentiment against German-born Fred Wolf Sr. and the fact that no Wolf men were enlisted in the war lead to the accusations and the guilty verdict. They insisted that disgruntled and fired employees and certain censured inspectors gave false evidence against them. Fred Wolf Sr. insisted he was an “innocent victim of misplaced justice.”

The Wolfs were installed in Leavenworth on February 17, 1923, hoping for a pardon from President Harding. The pardon was not granted. In Leavenworth, the Wolfs were assigned “light work” mail room jobs. Ironically, one of Paul’s tasks was inspection.

The Wolf lawyers filed an appeal for a pardon or parole. Their petition was signed by eleven jurors; eight stated they would not have signed the verdict had they known prison might loom for the men. Judge Fitzhenry, himself, recommended parole because of Fred Sr.’s age and poor health. Quincy citizens also created a petition soliciting leniency.

The pardon was granted. Fred Sr.’s, sentence was cut by eight months and Paul’s by 16 months. The weakened elder Wolf was released June 17, 1923.

Upon Paul’s release on October 17, 1923, The Quincy Daily Journal reported-- as if he had been on a sabbatical instead of in a four-year nightmare-- “Paul Wolf will resume his position as a member of the Wolf Manufacturing Company at once and again take his place in the social and commercial affairs of the community.”

The Wolf family operated the company throughout the legal process but by the end, the Wolfs had sold their leather operation and were producing radios and radio cabinets instead. In 1927, they moved their enterprise to Kokomo, Indiana.

Sources

“Erased Rejected Stamps.” The Quincy Daily Herald, November 5, 1919.

“Fred And Paul Wolf Give Their Side Of Case Against Them.” The Quincy Daily Herald, April 18, 1922.

“Fred Wolf And Son, Paul, Are Held For Trial.” The Quincy Daily Whig, February 22, 1919.

“Fred Wolf Arrested, Charged With Defrauding Government,” The Quincy Daily Journal , August 20, 1918.

“Industrial Romances Of Quincy,” The Quincy Daily Journal, September 27, 1925.

“Stylish Marriage.” The Quincy Daily Journal, November 19, 1903.

“Wolfs Charged With Fraud.” The Quincy Daily Journal, August 21, 1918.

“Wolf Conviction Is Upheld By the U.S. Court of Appeals.” The Quincy Daily Herald, April 12, 1922.

“Wolfs Disregarded The Rejections Made By Gov’t Inspectors, One Testifies.” The Quincy Daily Whig, September 4, 1919.

“Wolfs To Face Trial.” The Quincy Daily Herald, April 4, 1919.