The Biggest Bank Heist in the Country

The day before Valentine’s Day,

February 13, 1874, dawned to reveal a gaping hole in the ceiling of the vault

of the First National Bank of Quincy. It would set the record for the biggest

bank heist in the entire country.

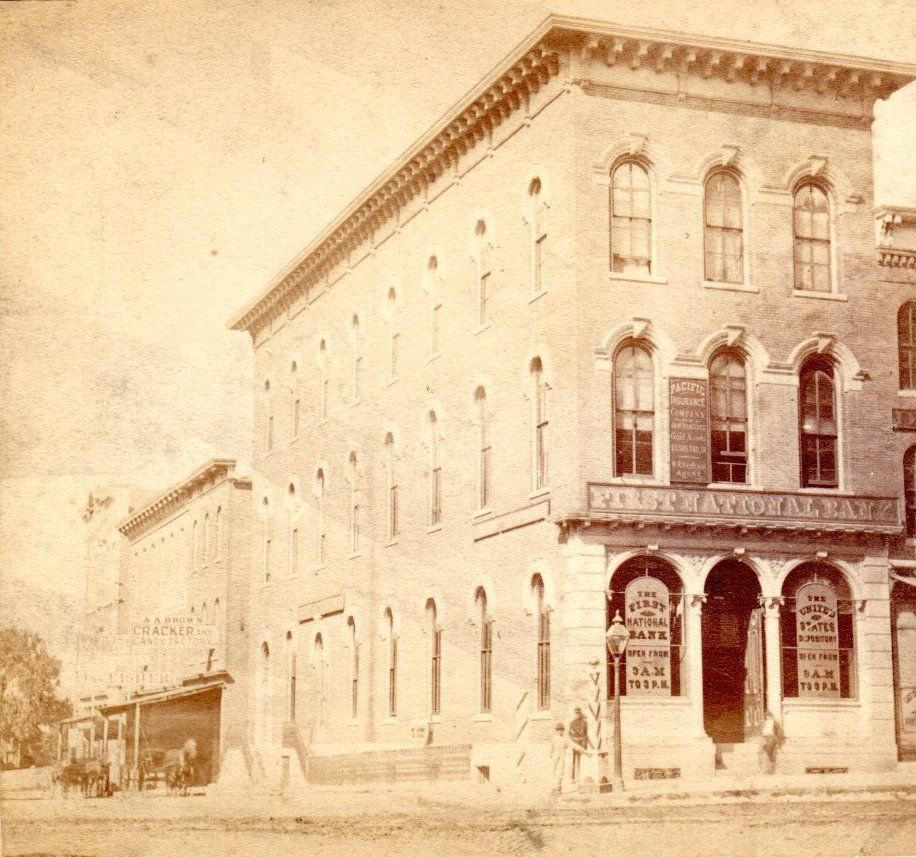

The bank, located at Fourth and Hampshire was chartered on May 30, 1864 and had experienced steady growth. Its balance sheet totaled over a million dollars at the time of the robbery.

At seven am, janitor William Cross entered the building and noticed plaster on the wall covering the vault was severely cracked. When he opened the door of an adjoining closet he found plaster from the ceiling lying on the closet floor, and a clock on the wall stopped at 2:17. He immediately notified officials who tried to open the vault door upon their arrival, but it would not yield. A machinist was sent for to force it.

Several men went upstairs to investigate. The second story of the building held the offices of the Q. M. & P. railroad, and the third story was used as a lodge meeting room.

The vault itself was eight feet square and made of iron surrounded by twenty-four inches of arched brick work reaching up to within four feet of the ceiling. The vault was located under the main hallway running east to west on the second story. Once upstairs, the men found part of the hallway floor had been taken away.

Two employees climbed down through the hole to the top of the vault where bricks had been removed and saw that a portion of the iron boiler plate covering the top of the vault was gone. The bricks that had been detached from above the vault were stacked haphazardly in spaces under the floor.

Dropping into the vault itself they found the doors of the double safe storing the banks’ funds had been blown off and the contents taken. Left inside the vault were various tools, according to the paper, “sledge hammers, saws, files and a quantity of rubber tubes, several powder flasks, some fuse and a pistol secured fast to a large blank-book.”

The tools indicated that the robbers tried to break open the safe before determining it needed to be blown. Black powder was worked in around the doors and a fuse run through a rubber tube, up to the second floor and out to the stairway. The pistol and the book contraption was a backup plan in case the fuse didn’t ignite the powder. The gun had a string tied to the trigger leading up to the second floor and out to the stairwell and could have been used to detonate the fuse.

The safe itself had a combination lock on the right hand door and the left door could only be unlocked after the first one was opened. The right side held the bank’s cash funds; the left had drawers holding valuables belonging to customers. On top of the vault was a smaller safe which had been left undisturbed. The explosion blew open both doors of the safe, and the thieves took about $80,000 in cash and gold. It was estimated that enough boxes to load a small wagon were taken from the right side. Translated into current terms the value of the cash alone would be about $1.8million.

The professionals who managed this robbery did it within a block of the police headquarters, in one of the busiest areas of the city and escaped, perhaps in a wagon, with no one noticing. The clock stopped at 2:17 a.m. fixed the time of the crime. A boy lodging in the basement thought he heard something heavy fall down but didn’t get up to investigate. He also said that for the two previous nights he heard someone walking in the building after it was closed and that last night someone knocked on his basement door, but he stayed very quiet and the person went away. Since the bank had installed a “telephonic alarm” no watchman was employed.

No one saw anyone suspicious in the days before the robbery, no mysterious strangers left on the train the morning after; no wagon was seen leaving in the night. The private boxes that were stolen were not inventoried but were rumored to contain amounts of valuables equal to another $100,000.

Capt. McGraw learned that a stranger calling himself Bigelow had rented a room on the third story of the nearby Walker Building. He left the night before saying he would not return for several days. Mrs. Walker said that about ten o’clock she heard two sets of footsteps coming down from his room followed soon after by another two men. Mrs. Walker found his conduct suspicious as Bieglow avoided all contact and conversation with others. His room was found unlocked but contained nothing incriminating, only his clothing and some scant furniture. He had rented the room to serve as an office, saying he was in the patent business. He took all his meals at the Capital restaurant and always took an extra meal with him in a basket, saying it was for his wife who was ill.

It was reported that one of the most infamous safe crackers in the country, Thomas Scott, had been sighted in the city about six weeks before the robbery, but that was not confirmed. It was later thought that he had rented a house on Oak Street where the other men stayed. A day or so after the robbery, two men purchased a horse, buggy and harness in town and drove north toward Warsaw. They left the rig and flagged down a train and disappeared, apparently taking the contents of the safe with them.

Scott was eventually caught and brought back to Quincy, but his guilt could not be proven and he was released. Another man, called “Little Dave,” alias Dave Cummings, later confessed to having a part in the robbery. He was tied to large heists in Jersey City, New Orleans, Omaha and Louisville. No one was ever convicted for the robbery.

Sources

“Bank Robbery,” Quincy Whig, 19 February, 1874.

“A Buried Secret,” Quincy Whig, 17 February 1876.

“Crime, Bold and Successful Robbery in Quincy Illinois,” Chicago Tribune , 14 February, 1874.

“Round the Town ,” Quincy Daily Journal , 10 January, 1926.

“Scott, Alias Riley,” Quincy Whig , 1 October, 1874.