The debate: Of raccoons and politicians

The second week of October 1858 began with rain, clouds and mud for residents of the Tri-State area. They were looking forward to the sixth debate between Abraham Lincoln and U.S. Sen. Stephen A. Douglas. The debate in Quincy's Washington Square might influence the make-up of the state legislature, which would choose the person to represent Illinois in the U.S. Senate.

The relief must have been palpable when after 16 rainy days the clouds parted and Wednesday, Oct. 13, dawned bright, mild and windy. Clear skies smiled on the bustle and scurry of debate preparations. Parades and preliminary ceremonies were scheduled for the morning with time out for dinner before commencement of the debate.

On the morning of the debate, Republicans welcomed the arrival of Lincoln from Macomb on the Burlington Line. In addition to the cannon and music and banners and transparencies --and girls on horseback representing the states--the principle attraction was a model ship on wheels drawn by four horses and labeled "Constitution." It was filled with sailors, and at the helm was a live raccoon symbolizing the former Whig Party and recalling its champion, Henry Clay. The parade escorted Lincoln to the home of Orville Browning on the southeast corner of Seventh and Hampshire, where he was welcomed by John Tillson, candidate for state senator. Lincoln was entertained, dined at the Browning home and, afterward, escorted the few blocks west to Washington Square.

Douglas remained in his hotel, the Quincy House at Fourth and Maine streets, as the Democrats paraded through town. They carried a huge likeness of their hero at the head of the procession, which one partisan reporter boasted was at least two miles in length.

The Republican procession, he added, was only "probably half a mile in length." Among the displays was a large number of flags on hickory poles, designed to characterize Douglas in the popular mind as "Young Hickory," as Andrew Jackson had been "Old Hickory." And suspended by its tail at the top of a pole was a dead raccoon, meant to insult the Republicans and serve as a symbol of triumph of the Democracy. The Chicago Press and Tribune reported, however, the display was an insult only to the Old Line Whigs.

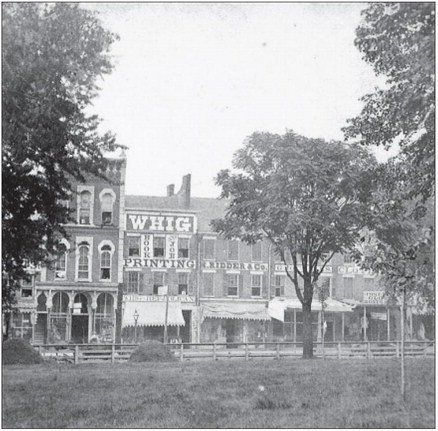

As the procession passed the Quincy House, Douglas stood at his second floor window where he was cheered by the waves of marchers as they passed. By noon, the excitement died down, and people dispersed to dinner before gathering for the debate in Washington Square across the street from the impressive Greek-columned courthouse, built twenty years earlier on the east side of the square. Douglas had presided there as circuit judge for the Fifth Judicial District, whose residents in 1843 elected him to Congress.

Washington Square was bounded by a stretch of irregular and unhandsome wooden awnings, which fronted most of the stores and shielded pedestrians from sun and rain. The square itself was weedy and unkempt. The streets around it were unpaved. Just outside the square were racks where farmers hitched their horses and parked their wagons. Now and again, truant cows escaped the farmers' wandering eyes and got a taste of the hay or corn or oats in the wagons--to be driven off by farmers and dogs and boys.

Long before the scheduled commencement of the debate at 2:30 p.m., a reporter described the town square as "pretty well filled up with a living, moving, multitude." A visitor recalled, "There was no end of cheering and shouting and jostling on the streets."

Banners and signs promoting both candidates filled the streets for the occasion. People came displaying hickory poles and flags until Quincy looked like a forest of hickories and flags. Douglas wore his finest clothes for the meeting, to which Lincoln came dressed as usual in his wrinkled suit and battered hat.

By debate time, the town was seething with people, and the loud, jostling crowd surrounded the large, pine-board platform built in Washington Square for the occasion. A few minor disasters delayed the proceedings. A railing along the stage gave way to the intense pressure of bodies wedged against it, sending a dozen dignitaries and a large bench crashing to the ground. Then another bench, set up in front of the platform for the benefit of the ladies, collapsed under their weight, and several of the dazed victims had to be assisted from the area.

When order was restored, Lincoln opened the debate in a voice German-American newspaper man and future U.S. Sen. Carl Schurz stated seemed "a shrill treble in moments of excitement." Sitting on the platform at Lincoln's invitation, Schurz gazed into the crowd while Lincoln spoke, convinced by "the looks of the audience ... that every word he spoke was understood at the remotest edges of the vast assemblage." That contrasted with some newspaper accounts which stated that not a hundred people heard the debate word for word.

The Democratic press insisted Douglas won the day by demonstrating "more than usual eloquence," while a Republican journal taunted that a "photographic agent" earlier seen hawking Douglas portraits during his rebuttal for 75 cents apiece, reduced his price to 60 cents midway through Douglas's speech and ended up pleading with his customers to take them off his hands for only 25 cents each.

After the debate, Lincoln walked to the Browning residence where he was greeted by many women who presented him with a bouquet. John Tillson made a short speech, and there was much hand shaking. When it was over, Lincoln said he wanted to take a short walk by himself. He left the Browning place and went to Ninth and Hampshire where he entered the Farmers Hotel and asked for a bed for an hour stating that he was weary and wanted a short rest. In a little less than two hours, he came downstairs, mingled with the guests for a short time and then went back to the Browning home.

Orville Browning (who would replace Douglas as Illinois' U.S. senator when Douglas died in 1861) was at court in Carthage and not present for the debate.

With the departure of both candidates on the steamboat City of Louisiana the following morning, each party was as sure as it had been at the beginning that on its side were truth and valor and that its hero had wrested victory from the enemy. Life in Quincy once again returned to normal.

Phil Germann is a retired executive director of the Historical Society of Quincy and Adams County, having served 19 years. He is a former history teacher, a local historian and speaker, a member of several history-related organizations and a civic volunteer.

Sources

Quincy Daily Herald. October 11-15, 1858.

Quincy Daily Whig. October 11-15, 1858.

Richardson, William A. Jr. "Pen picture of the Central Part of Quincy as it was when Lincoln and Douglas met in Debate, 1858." Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society. Springfield, Illinois: Illinois State Historical Society, July 1925.