'Day of Jubilee': Emancipation Proclamation

In 1881, 18 years after the Emancipation Proclamation, former slave and abolitionist leader, Frederick Douglass, recalled the excitement and joy experienced on Jan. 1, 1863, when President Lincoln's proclamation became effective.

Douglass stated, "Remembering those in bonds as bound with them, we wanted to join in the shout for freedom, and in the anthem of the redeemed."

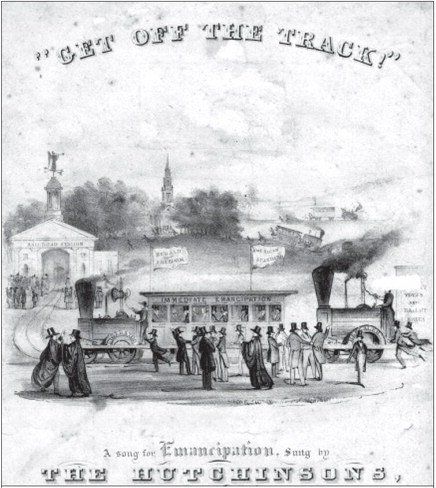

The Emancipation Proclamation fulfilled the dreams of African Americans by pledging to free all slaves in the states still in rebellion and allowing for the service of able bodied African American males in the Union Army. Lincoln's Proclamation represented the culmination of years of struggle over the issue of slavery, the desire to maintain the Union and win the Civil War. Douglass described the Proclamation as being "slowly wrung" from the president, a claim that was evident in the progression of Lincoln's policy, which shifted from his rejection of Fremont's emancipation of slaves in Missouri to suggestions of gradual abolition and eventually to the final draft of the Proclamation. It is then no wonder that African Americans lauded the Proclamation and exclaimed that this was the "Day of Jubilee."

In Quincy, the African American community echoed the joy expressed by Douglass. Members of the African Methodist Episcopal Church resolved to thank God for his "interposition in behalf of the oppressed colored race in this land." Quincy's African American population totaled around 150 at the time of the Civil War, but 36 men attempted to enlist in the Union Army and 25 would eventually leave Quincy to serve. Moreover the town became the recruitment center for the First Illinois Colored Regiment also known as the 29th U.S. Colored Infantry in the later part of 1863. Quincy's African American community created a set of resolutions in response to the enlistment of colored soldiers declaring that, " ... we as colored people ... deem it to be the duty of all able bodied men ... to go to war." The 29th consisted of free men from Illinois but also slaves from their neighboring state, Missouri, and other areas throughout the Midwest. After departing Quincy in April 1864, the 29th saw action at the Battle of the Crater, Petersburg and Richmond.

Although the Emancipation Proclamation brought joy to the hearts of African Americans living in Quincy, not every citizen agreed with the president's policy. One white soldier offered his thoughts on emancipation, stating, "I did not come here to fight for the negroes." Additionally, the prospect of an increasingly large African American population disturbed white citizens of Quincy and throughout the Midwest. Years earlier, in an 1857 address in Springfield, Lincoln described this sentiment in reference to the Kansas-Nebraska act explaining that there is a "natural disgust in the minds of nearly all white people to the idea of indiscriminate amalgamation of the white and black races ... "

Emancipation's diaspora meant an increase of African Americans to this entire region including, Illinois, Iowa, and Indiana. Illinois' "black laws," some of which were legislated as recently as 1853, were meant to prohibit African Americans from entering the state by fining and imprisoning anyone that attempted to bring a person of color into the state for up to a year. African Americans who tried to settle in Illinois could be fined $50. Quincyans commented on the increasing black population in the newspapers, revealing their conflicting emotions over the changing environment of the wartime city. In nearby locations such as Keokuk, Iowa, the white community began to actively enforce "black laws" and tried to remove African Americans that entered into their community.

Although emancipation created anxiety for some citizens of Quincy and its neighboring communities, the Proclamation also provided hope for those African Americans that remained enslaved in Quincy's westward neighbor, Missouri. The Proclamation carefully chose to emancipate only those slaves living in states that were in rebellion, which excluded the loyal slave state of Missouri. Although evidence suggests that many slaves were not aware of the proclamation, as word spread of its message, slaves became agents in their own emancipation, finding ways to break down the bonds of slavery.

In St. Louis, news of the Proclamation amongst the enslaved black population was described as a "torrent of oil onto a burning city." For those slaves unable to run away or join the ranks of the Union Army, the Proclamation encouraged resistance and the rejection of white authority within households and communities. Others physically abandoned slavery by running away from plantations and farms, joining the army of those seeking refuge in cities like Quincy. This led to the formation of Quincy's Contraband Aid Society in 1863 for African Americans in need.

Ultimately the impact of the Emancipation Proclamation was far reaching and varied in Quincy and its surrounding communities. But most importantly the Proclamation promised to the citizens of Quincy, Illinois and the nation, that slavery would be eradicated in the United States.

As Frederick Douglass explained, "We are all liberated by this proclamation ... It is a mighty event for the bondman, but it is a still mightier event for the nation at large."

Megan Boccardi is an assistant professor of history at Quincy University . She received her doctorate from the University of Missouri-Columbia. Her research interests include the Civil War and Reconstruction, Southern women, and African American history.

Sources:

Berlin, Ira, Barbara J. Fields, and Steven F. Miller. Slaves No More: Three Essays on Emancipation and the Civil War. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992.

Berlin, Ira, Joseph Patrick Reidy, and Leslie S. Rowland. Freedom's Soldiers: The Black Military Experience in the Civil War. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998.

Berlin, Ira, et al., eds., The Black Military Experience. Series II in Freedom: A Documentary History of Emancipation, 1861-1867. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1982.

Blight, David. Frederick Douglass' Civil War: Keeping Faith in Jubilee. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1989.

Camp, Stephanie. Closer to Freedom: Enslaved Women and Everyday Resistance in the Plantation South. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2004.

Costigan, David. "A City in Wartime: Quincy, Illinois and the Civil War." PhD diss., Illinois State University, 1994.

Quincy Herald

Quincy Whig

Schwalm, Leslie. A Hard Fight for We: Women's Transition from Slavery to Freedom in South Carolina. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1997.

------. Emancipation's Diaspora: Race and Reconstruction in the Upper Midwest. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2009.