Town anticipates Lincoln-Douglas debate

The most significant day in Quincy's history was Oct. 13, 1858.

Thousands headed for Quincy from throughout the area for an event they knew was significant, one which they would tell their children and grandchildren about for decades to come. U.S. Sen. Stephen Douglas and Abraham Lincoln were to meet in the sixth of seven debates, hoping to influence the election of their supporters to the state legislature, which would choose the person to represent Illinois in the U.S. Senate.

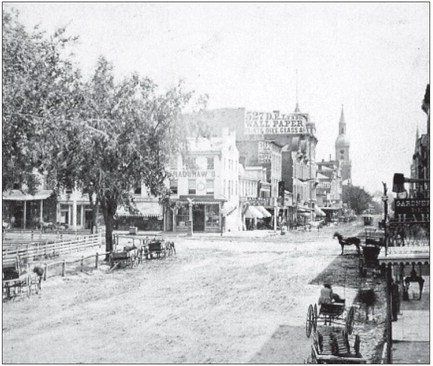

In 1858, Quincy was the third largest city in Illinois with a population of nearly 10,000. Its inhabitants came from two sources. The first was a tide of settlers from New England and the Middle Atlantic States that began in the 1830s. Internal improvements --c anals, steamboats, roads, and railroads -- made a western move more feasible than it had been a decade or two earlier. When the railroad linked Quincy with the East in the 1850s, the influx became a veritable flood. The naming of the community's east-west streets (Maine, Vermont, Hampshire, Delaware, Ohio, and Jersey) is a reminder of these settlers' origins.

The second group of Quincy residents was foreign in origin: primarily German and Irish. By 1860, the foreign-born population comprised more than a third of the residents of the "Gem City," a title used because Hannibal, Mo., had appropriated the more logical title, "The Bluffs City."

The wave of humanity into Quincy was due partly to untapped farmland surrounding the town. One Boston visitor exclaimed, "What a soil for a New England farmer to luxuriate upon. The very weed which barely reach in Massachusetts to the height of six inches, here run up to as many feet. The earth puts forth her produce with an abounding fertility such as never dreamed of by our industrious population at home ... with such advantages as nature holds out, man cannot go far aside from the path of plenty."

With its advantageous position on the Mississippi, industries sprang up rapidly. Grain was exported, primarily wheat, corn, and oats. Pork packing, which took place only in the cold period between October and February, flourished. By the 1850s, Quincy was shipping over 5 million pounds of packed pork which became a staple in the diet of slaves on Southern plantations. Flour milling, machine shops and foundries, cooperages and brickworks, distilleries, stove and wagon manufacturers and breweries rounded out Quincy's industrial picture.

These industries were so successful that one writer predicted in 1857, "It rests with the citizens of Quincy, to make her in the very few years, a city of 100,000 inhabitants: the manufacturing and commercial centre of as highly favored scope of country as the sun shines upon."

As Quincy grew, river traffic increased. Two packet lines ran daily to St. Louis, and one line ran to Keokuk, Iowa. In 1853, the U.S. Congress designated Quincy a port of entry for foreign goods, placing it in the customs collection district of New Orleans. Ships could now arrive in Quincy from New Orleans with European goods and immigrants and return loaded with flour and pork. In 1856, Quincy saw 2,921 steamboat arrivals and departures carrying both passengers and freight.

On the eve of the debate, a correspondent for the Chicago Press and Tribune wrote, "I had occasion to go over into Missouri, and there I found large handbills up calling on the Democrats of the State to turn out at Quincy. Several steamers have been engaged by the Missourians to convey them up the river. I was told by several of them that they intended to make Lincoln ‘dry up.' What they meant by it, I do not know. Douglas's friends in Quincy are looking to Missouri for their crowd on the 13th."

Republicans were just as zealous. About 20 miles upriver in Keokuk, Iowa, the Republican Committee arranged to provide excursions for its followers on the steamers Keokuk and St. Louis Packet. The latter boat was scheduled to leave at 6:30 in the morning of the 13th from Keokuk and at 6 p.m. from Quincy. The roundtrip fare, supper included, was $1.50. Other boats with picturesque names like Hamilton Belle, Colonel Morgan and City of Louisiana brought spectators from various points along the river.

With a multitude of political partisans and general populace expected to occupy the streets of Quincy, both sides were determined to avoid conflict which might result in rowdiness. Each, therefore, published the order of procession of its pre-debate parade in its own press several days before the debate with a request to rival papers to "please copy." And so, it was arranged that, when the bands and carriages and marchers and horseback riders of one faction were parading up one street, those of the other would be coming down an adjacent street. While the noise and music might occasionally mingle, there was no chance of the processions colliding.

The Democrats got off to an earlier start than the Republicans. They began their celebration the evening before with the arrival of Douglas from Augusta and Camp Point. A huge torch light procession greeted the Little Giant at the railroad depot at the river front to the booming of cannon and the blare of music, and escorted him to his quarters at the Quincy House on the southeast corner of Fourth and Maine.

Several days after the debate, the Quincy Herald reflected on Judge Douglas's reception. "The most magnificent display that has ever been made in this city, was made by the Democracy on Tuesday last, on the occasion of the reception of Judge Douglas. Our distinguished Senator was received at half past nine o'clock at the rail road depot amid the booming of cannon and a most splendid display of torch lights and transparencies, accompanied by the welcoming, enthusiastic shouts of not less than three thousand live Democrats.

Four hundred blazing torches, and beautiful transparencies in proportion, with bands of music and a procession more than half a mile in length, and the streets of the city literally thronged with people, in honor of the great statesman of the day, was a sight that did the hearts of the Democracy good to witness, while it struck terror to the hearts of their black republican foes.

Judge Douglas was escorted by the procession to the Quincy House, where, with three times three hearty and enthusiastic cheers, the Democracy left him for the night, repairing, however, to the public square, where they were addressed in a most able, entertaining and unanswerable manner by Dr. Bane, after which, the demonstrations of the evening were brought to a close.

The black republicans themselves admit that nothing equal to this demonstration made by the friends of Judge Douglas, on Tuesday evening last, has ever been seen in Quincy."

Supporters of Lincoln looked forward to the next day in hopes with the arrival of their candidate, Republican ideas and enthusiasm would carry the day and wrest victory from Douglas and his supporters.

Phil Germann is a retired executive director of the Historical Society of Quincy and Adams County, having served 19 years. He is a former history teacher, a local historian and speaker, a member of several history-related organizations and a civic volunteer.

Sources

Brown, Thomas J. "The Age of Ambition in Quincy, Illinois," Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society. Springfield, Illinois: Illinois State Historical Society, Winter 1982.

Quincy Daily Whig. October 11-15, 1858.

Quincy Daily Herald. October 11-15, 1858.