The elegance of Steamboat Mary

Dozens of friends joined Mary Otte of Quincy on March 15, 2013, to celebrate her 100th birthday. Friends stood and knelt beside the chair in which she sat to introduce themselves, share a recollection or two, and wish her well.

The introductions were not because Otte could not remember the names of her guests. Her vision was impaired by eyes that began failing a few years earlier. Her memory, however, was sharp and clear and crisp and it informed her conversations throughout the afternoon. Petite, mannered, and welcoming, she was animated by the reminiscences. Her own vignettes throughout the afternoon added sparkle to her party.

One of Otte's well wishers asked her to say something about her experiences working on steamboats. She brightened and turning toward her inquisitor smiled in a way that expressed surprise that someone knew about the years she had spent on the river.

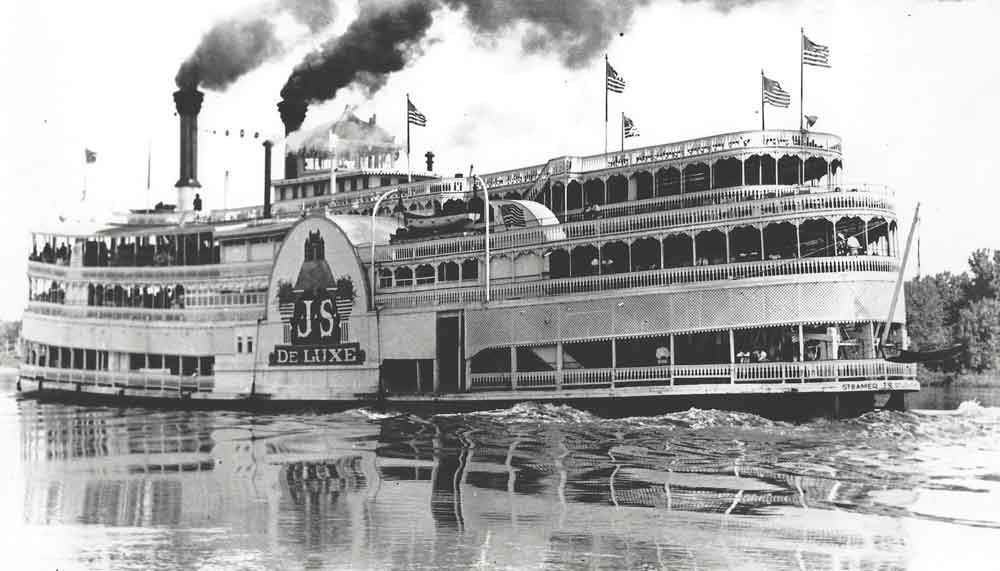

Her reflections took Otte's listeners to 1932 and her opportunity to work on an excursion boat, the J.S. Deluxe. The boat, named for John Streckfus, was one of five steamboats operated by Streckfus Steamers Inc. of St. Louis. The Deluxe was considered the company's "brag boat." The four-deck J.S., as her crewmen spoke of her, was then the largest, fastest, and most elegant boat of the Streckfus company's steamers. The firm was more recently known for its St. Louis-based Admiral, an all-steel art deco-styled steamer built in 1940 and dismantled in 2011.

John Streckfus had foreseen the impact railroads would have on riverboat freight business and refocused Streckfus Lines on the excursion trade. Staterooms and cabins were removed to enlarge the salon, or main hall, for large dance floors and bandstands. The J.S. Deluxe could board as many as 2,000 passengers. The first J.S. in 1901 was outfitted for the firm's specialty trips of day, afternoon, and evening cruises. Customers boarded and returned to stops all along the river between St. Paul to New Orleans. Quincy was one of them.

"The boat carried excursions from Quincy long before I ever dreamed I would live here," said Otte. "A trip ran back and forth to Hannibal all day. People could get off at Hannibal and re-board two hours later to come back.

"Organizations like a young men's group from St. Francis would book cruises ahead of time. They got commissions for tickets they sold in advance. The St. Francis group made the Moonlight Cruise on the Capitol and would go upriver for senior prom."

At 19 years old, Otte signed on as a purser's assistant at $14 a week on the second J.S. Deluxe. Her job opened to her a world of rivers and ports, big bands and dancers who traversed the large maple floors to rhythms in four-four time. They would return to elaborate accommodations along the bulkheads or move outside to a promenade that wrapped the boat's perimeter, where on the port side they could listen to the side wheeler's paddles slapping the river.

Otte's work introduced her to luminaries and river men, trained her in business practices, and acquainted her with Quincy when the J.S. stopped here. It also introduced her to Quincyan William Otte, a steamboat steward and mate. When she married him in 1936, he was the pilot on the Streckfus Line's S.S. Capitol.

Whether Otte knew it when she joined the crew, the J.S. Deluxe had connections to the Quincy name. The Diamond Jo Line of Dubuque, Iowa, had operated four steamboats in succession named for the City of Quincy. The Streckfus firm acquired the fourth Quincy and three other steamboats when it bought the Diamond Jo Line in 1911. This last Quincy, 264 feet long and 42 feet wide, was converted to an excursion boat during the winter of 1918-19 and was renamed the J.S. Deluxe that spring. It replaced the first J.S., which burned in June 1910.

Otte's first job was to count money and relieve cashiers at the several stations on the boat as it "tramped," or cruised, the Mississippi River for the excursions at one port and the next.

"They always had a day trip, which was a picnic affair -- people came with big baskets of food," Otte recalled. "Streckfus had a reputation for having very good bands, so the night trips were called Moonlight Cruises and were strictly for dancing."

Otte remembered that bands like Louis Prima's and Fate Marable's were big draws for the Midnight Cruises. Marable was the Streckfus Line's star bandleader, attracting musicians like cornetist Louis Armstrong, drummer Warren "Baby" Dodds, and Bassist George "Pops" Foster.

At the end of her first season on the river, Otte became a secretary to Captain Roy Streckfus on the company's S.S. Capitol, which during the winter operated from New Orleans. The Capitol's two-week tramp from Quincy to New Orleans added to Otte's repertoire of memories.

On one trip, while the boat took on coal at Natchez, Otte decided to sightsee. Not far inland she was attracted to a palatial home, its wide front sidewalk flanked by blossoming trees. She asked a woman sweeping the walk if she could pick a flower and confirmed it was a magnolia blossom. Later at lunch, the captain said the wife of the coal company owner had invited the women of the crew to see the antebellum mansions in the area.

"Two of the girls and I did," Otte said, "and we passed this same house. Spontaneously, I said I have been there. Our host seemed surprised and asked under what circumstances. I said I was there and picked a magnolia. She laughed and said, ‘Why, Mary, that is the biggest whore house in Natchez.'"

Capt. Streckfus dictated a supply order to Otte that was to be delivered to the boat when it reached New Orleans. Streckfus told her the supply house was on Tchoupitoulis Street.

"I thought I'll be darned if I ask him how to spell that," she said. "There was a telephone directory in the office and I thought I could just look that up."

She searched page after page for the spelling, and since the T in the street name was silent, she was unable to find it. Otte was embarrassed that she had to ask Streckfus for the spelling. She was relieved to learn, however, that two New Orleans policemen, who had found a drunk on Tchoupitoulis Street, had as much trouble with the name when they had to spell it on a police report. One of the policemen suggested a solution:

"Let's just drag him around to Ramparts Street," he said.

After the season aboard the Capitol, Otte returned as purser on the J.S., which tramped the Illinois, Mississippi, and the Ohio rivers as far east as Parkersburg, Va. She recalled a time at New Orleans when the pre-teenaged son of Louisiana's colorful Governor Huey Long and two bodyguards entered her office to get the boy change to play the pinball machines.

"I did not have enough nickels and dimes," she said, "so I leaned over to work the combination on the safe, and he slapped me on the rear. I swung around to slap him but didn't make contact, not because of the bodyguards but because he was just a boy."

Otte's daughter, Shirley Kueter, told the story years later to a senior partner of the law firm at which she worked. The partner, who happened to be involved in business with then-U.S. Sen. Russell Long, told the story to the senator. Long sent Otte his personal apology.

In addition to accounting for the boat's revenue from its ticket and concession sales, Otte was responsible for paying the crew. Deckhands were usually African- Americans from the South. When she noticed that most signed for their pay with an X, she asked if they would like to learn to sign their names. Most said yes.

"We would gather in the office, take some cardboard, and take them by the hand and together we would write their name. They would take their cardboard with them and practice. In a couple of weeks they could sign their name."

Otte worked five years for the Streckfus Line. She retired 20 years after serving as secretary to the principal of Quincy High School, then volunteered for 20 years with the Quincy Ladies of Charity, serving others. She had been the treasurer until failing eyesight forced her to retire once again.

Reg Ankrom is a member of the Historical Society of Quincy and Adams County, the author of a narrative history of Stephen A. Douglas, and a frequent speaker on pre-Civil War history.

Sources

David Dulaney, interview with the author, October 4, 2014.

Dean Gabbert, Brown-Water Boating: Tales of Riverboats & Coast Guard Cutters.

Florissant, Missouri: Little River Books, 2007.

Mary Otte, interview with the author, August 15, 2014.

"The Streckfus Steamboat Line," http://jazz.tulane.edu/exhibits/riverboats/gallery

John Tillson Jr., History of Quincy. Chicago: S.J. Clarke Publishing Co., 1905