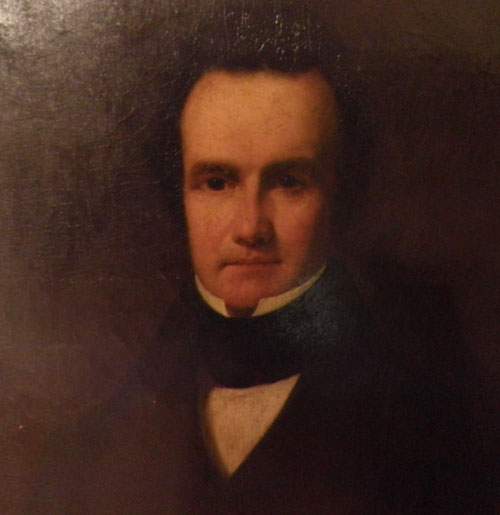

The life of Hon. Stephen A. Douglas

Even as her son on June 24, 1833, awkwardly climbed aboard a stagecoach to leave his Canandaigua, N.Y., home, Sarah Arnold Douglas pleaded with him once more not to go. Illness had frequently visited the 20-year-old Stephen Arnold Douglas, but he was determined to go west. Resigned that her pleas would be ignored, Mother Douglas asked her son when he would return to see her.

"I will stop by and see you on my way to Congress within the next 10 years," he answered.

Ten years later, Douglas kept his promise, thanks to Quincy area voters who on Aug. 7, 1843, elected him their representative in Congress.

Douglas arrived in Quincy on March 4, 1841. For several weeks he resided in John Tillson's Quincy House hotel at Fourth and Maine streets and then made his official residence for the next seven years at a small brick Greek Revival-style home on the southeast corner of Third and Jersey.

Douglas came with a reputation as the "Little Giant," a towering Democratic politician whose unusually short legs limited him to a height of only 5-foot-4. Less than a week earlier, after taking an oath of office that he wrote on a half-sheet of foolscap for his swearing-in, he became an Illinois supreme court justice and circuit court judge of the state's Fifth Judicial District. The post, based in Quincy, was the last step he planned --and Douglas planned every move he made in his career -- en route to satisfying his promise to his mother, as well as his own ambition.

It was by his own making that Douglas became justice and judge. At 27 years old, he had engineered his way onto the bench of the state's highest court, the youngest justice in Illinois history. It is a record he still holds and which jurists say is unlikely to be broken.

"Engineered" is an appropriate word for the manner of Douglas' achievements. From the time he arrived in Jacksonville -- he wanted to meet the people who named their town for his hero, Andrew Jackson -- on Nov. 13, 1833, Douglas designed his own political destiny. His path seemed to be without obstacle. In the seven years before his appointment to the bench in Quincy, Douglas seemed to lead a charmed life without setback. After becoming a lawyer more interested in politics than practice, he wrote a bill to change the way state's attorneys were appointed, then won appointment to the office in the large First Judicial District, headquartered in Jacksonville. In doing so, he booted from office John J. Hardin, one of Illinois' most powerful Whigs and a nephew of Abraham Lincoln's ideal politician, U.S. Sen. Henry Clay of Kentucky.

Douglas masterminded the creation and assumed the leadership of the first Democratic Party organization in Illinois in 1835 and the next year was elected a state representative from Morgan County. He resigned that post when President Martin Van Buren appointed him register of the federal land office in Springfield. Douglas started that job in March 1837, moving to Springfield just a month before his tall legislative colleague, Lincoln of New Salem did.

Douglas saw an opportunity to advance his political career when Missouri Gov. Lilburn Boggs in October 1838 ordered 5,700 Mormons out of Missouri or be killed. During the winter of 1838-39, the desperate Latter-day Saints fled east from far west Missouri. In February they streamed across the frozen Mississippi River to Quincy, whose 1,500 citizens provided shelter and comfort to them.

When Church representatives sought to charter a new community on the banks of the Mississippi just north of Quincy, Douglas persuaded Gov. Thomas Carlin, a Quincy resident, to appoint him Illinois secretary of state. In that position, he promoted and signed the charter that made Commerce, Illinois, the City of Nauvoo, ingratiating himself with church founder Joseph Smith. With Nauvoo -- and Mormon affections -- established, Douglas, secretary for only three months, resigned.

Douglas' next move was an outlandish partisan scheme to make himself a member of the Illinois Supreme Court. He wrote a bill to reorganize the court -- and reorganize justices' duties as well. Only five years earlier, Douglas had won a change in law that removed circuit court duties from the four Supreme Court justices. Three justices were Whigs, and Douglas' goal was to limit their opportunity to politick while traveling the circuit. Now, Douglas' bill to pack the court restored circuit duties to the justices for precisely the purpose of enabling him to politick on the 11-county Western Illinois circuit.

Politick he did, and at every opportunity. A New York lawyer visiting his court room was stunned to see Douglas leave the bench while a trial was underway, light a cigar and plop his short frame atop the lap of a familiar attorney. Even in such informality, Douglas instructed a lawyer presenting his case to return to the point.

As self-serving as Douglas' actions were, his fellow lawyers and historians credit Douglas with mastery on the bench. He ordered attorneys to settle languishing cases. In his first stop in Fulton County, he disposed of 300 cases, some of which had been on the docket for seven years.

Whig lawyer Justin Butterfield of Chicago, who earlier deprecated Douglas' acumen in law, became an admirer.

"He listens patiently, comprehends the law and grasps the facts by intuition; then decides calmly, clearly and quietly and then makes the lawyers sit down. Douglas is the ablest man on the bench today in Illinois," Butterfield said.

Among Douglas' first cases was an extradition order from Missouri for the return of Mormon Prophet Joseph Smith so he could be tried for treason. Douglas ruled the order invalid since it had been returned unexecuted the previous year by the Hancock County sheriff.

"Douglas is a Master Spirit, and his friends are our friends," Smith wrote. " ... We will never be charged with the sin of ingratitude -- they have served us, and we will serve them."

Among Douglas' most celebrated cases over which he presided was the trial in 1842 of his Quincy neighbor, Dr. Richard Eells, whom he convicted of aiding a fugitive slave from Missouri. Douglas fined Eells $400, half the value of the slave. Eells appealed the ruling to the Illinois and U.S. supreme courts, each of which upheld Douglas's decision.

Douglas was elected Aug. 7, 1843, to his seat in Congress over Whig lawyer Orville Hickman Browning of Quincy. Whigs sought to neutralize Douglas' popularity by portraying him as a "striving politician" interested only in collecting political support to serve his own ambitions, said the Quincy Morning Whig. He did not pay taxes in Quincy, the newspaper charged, adding that his only goal was "to live off the people."

Browning and Douglas campaigned -- and lived -- together for 40 days, excluding Sundays. They traveled, ate, joked, and on occasion slept in the same bed together, and battled each other in political oratory for up to six hours each day. By the end of the campaign each man was exhausted, and Browning was forced by illness to bed. Douglas won by only 416 votes out of 17,069 votes cast. He did not get the Mormon vote as expected, but friend Gustav Koerner of Alton brought him the region's German vote.

In November 1843, Douglas left Quincy for Canandaigua, N.Y,, to keep his 10-year-old promise to his mother.

On Dec. 4, Stephen A. Douglas took his seat in the U.S. House of Representatives, where a constitutional crisis had erupted. Speaker John Jones, a Virginia Democrat, called on Douglas, the former Illinois Supreme Court justice, to find a constitutional resolution. Douglas soon returned his report, which ended the crisis, the first of many he would resolve over the next decade.

On Dec. 17, 1844, he introduced his first bill -- a measure to organize the Nebraska Territory. It was his first effort in the work to which he dedicated himself for the next decade: " ... to make this an ocean-bound Republic." Douglas would find, as his elder House colleague, former President John Quincy Adams observed, that slavery was connected with every bill that came before the house. Douglas found ways to mollify his southern colleagues for a decade. Until his Kansas-Nebraska bill in 1854.

Reg Ankrom is executive director of the Historical Society. He is a member of several history-related organizations, the author of a history of Stephen A. Douglas and a frequent speaker on pre-Civil War history.

Sources

Ankrom, Reg. "The Political Apprenticeship of Stephen A. Douglas: Illinois, 1833-1843." Unpublished manuscript.

Black, Susan Easton and Richard E. Bennet, eds. A City of Refuge: Quincy, Illinois. Salt Lake City, Utah: Millennial Press, 2000.

Douglas, Stephen A. The Letters of Stephen A. Douglas. Edited by Robert W. Johannsen. Urbana, Illinois: University of Illinois Press, 1961.

Johannsen, Robert W. Stephen A. Douglas. New York: Oxford University Press, 1973.

Milton, George Fort. The Eve of Conflict: Stephen A. Douglas and the Needless War. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Riverside Press, 1934.

Pease, Theodore Calvin, ed. Illinois Election Returns, 1818-1848. Springfield, Illinois: Illinois State Historical Society, 1923.

Quincy Daily Whig. August 2, 1843.