Two Quincyans influenced outbreak of Civil War

Abraham Lincoln was comfortably settled into his Springfield law practice when Congress passed the Kansas-Nebraska Act in 1854. It was the alarm that returned him to public life.

"I was losing interest in politics," wrote Lincoln to Joshua Speed, with whom he had boarded in Springfield between 1837 and 1841, "when the repeal of the Missouri Compromise aroused me again."

That compromise brought Missouri into the Union as a slave state in 1821, and with the exception of Missouri, kept slavery below its southern border for more than three decades. But the Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854 repealed slavery's boundary and replaced it with "popular sovereignty." That meant settlers would decide by their votes whether slavery would expand into new federal territories. Lincoln had no argument with democratic principles, but he was shocked that Congress would ignore the immorality of human slavery and risk its expansion. He predicted the measure would cause civil war.

If, as Lincoln suggested, the Kansas-Nebraska Act would provoke a war between Northern and Southern states, then it was two Quincyans who could be held responsible for the U.S. Civil War.

U.S. Sen. Stephen A. Douglas, a Quincy resident from 1841 to 1848, wrote and won passage of the bill in the Senate. And it was Douglas' lieutenant in the lower House, Quincyan William Alexander Richardson, who won its passage there. Richardson had the more difficult task. The House was where America's great abolitionists, including his city's namesake, John Quincy Adams, fought slavery's expansion. But for Richardson's political ability, they might have killed Kansas-Nebraska and the potential for civil war.

Richardson left Fayette County, Ky., in 1831 and was 20 when he arrived in Shelbyville, Ill. He would have made Shelbyville his home until a fistfight with a popular local doctor forced his departure.

A biographer wrote that Quincy's Orville Hickman Browning, with whom Richardson studied law, found him "lacking polished manners and a well-informed mind" but "a spirited and loyal worker. He laughed, drank, swore, and fought with relish. His political strength was considerable, and he was seldom defeated in his many bids for public office."

Although poles apart politically, Browning and Richardson were friends, both in Quincy and later, in Washington. They traded personal and political favors, and Browning's diary notes that they visited in each other's homes.

Richardson lived 15 years in Rushville, having admired the area while a militiaman during the Black Hawk War in 1833. Rushville was located in the Illinois Military Tract, and legal work and litigation over land titles kept lawyers busy.

An occasional visitor to the state capital at Vandalia, Richardson met Douglas there in early 1835. Douglas was promoting a bill to transfer to the Democratic legislature the governor's power to appoint states' attorneys. The legislature passed the bill and appointed Douglas state's attorney of the First Judicial District, in Morgan County. He persuaded legislators to appoint Richardson state's attorney in the Fifth Judicial District, which included Adams County.

At the first trial he prosecuted in Quincy, Richardson met several of the city's legal talents: presiding Judge Richard M. Young, soon to be a U.S. senator; grand jury foreman and Quincy founder John Wood; and attorneys Archibald Williams and J.H. Ralston.

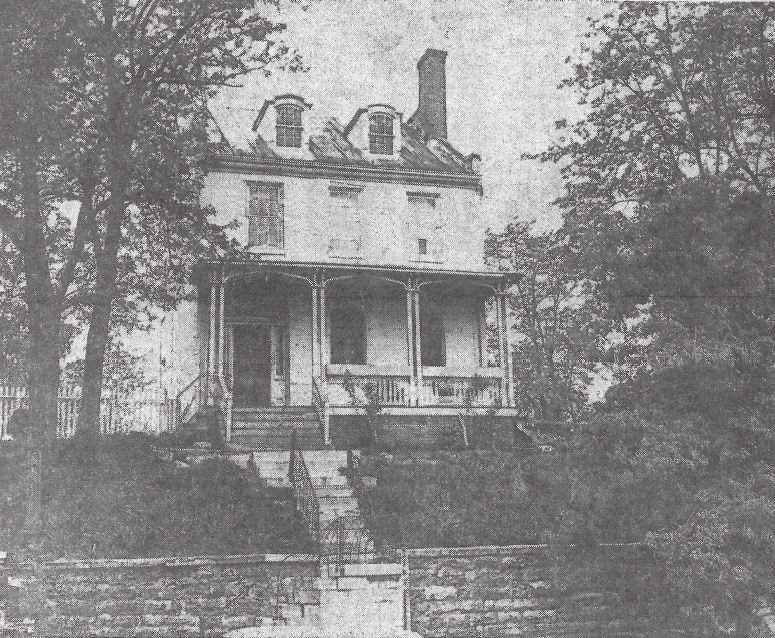

In Quincy, Richardson also met red-haired Cornelia Sullivan, whom he married in her mother's home in 1838. They lived in an imposing three-story brick home on the southwest corner of Fourth and Broadway until Richardson's death on Dec. 27, 1875.

Douglas and Richardson resigned as prosecutors in 1836 when elected state legislators. Richardson advanced to the Senate in 1838, served two terms, and retired to practice law. When Whigs in 1844 drafted James W. Singleton Jr. of Mount Sterling to run for the Illinois House, Democrats pleaded with Richardson to run against him. Once again, Richardson won election. On the strength of his victory, legislators elected him House speaker on the first ballot.

The Legislature promoted Douglas to the U.S. Senate in 1847. Voters that year sent Richardson, just back from the Mexican War, to take Douglas' place in Congress. Richardson introduced resolutions supporting President James Knox Polk and the war. Congressman Lincoln responded with his "Spot Resolutions," demanding the president prove Mexico had provoked the war. Lincoln's anti-war stand was unpopular with Illinoisans, and he did not seek re-election.

Congressional friends nominated Richardson for House speaker. When the race dragged on, he suspected slavery was behind the delays. He thought the Union "strong enough to ride the storm that now threatens us." But his alarm was apparent when he added, "I pray God it may be so."

The slave controversy grew more strident when Congress debated its expansion into the huge territory acquired after the Mexican War. With Douglas leading the effort, the Compromise of 1850 relieved the slave storm and secession threats. But peace was fleeting. Within four years, Douglas and Richardson's efforts to organize the Nebraska Territory again raised the specter of slavery's expansion. The Kansas-Nebraska Act passed quickly in the Senate. But buried under 50 bills in the House, its passage seemed doomed. Using parliamentary maneuvering, however, Richardson brought Kansas-Nebraska to the top. To expedite the process, he substituted Douglas' senate bill for the House version. Then, by striking the enacting clause, a non-debatable motion, he required that a vote be taken. Still, opposition was fierce. Dozens of attempts failed to prevent a vote. Richardson waited for the right moment to call for the vote. When he did on May 30, 1854, Kansas-Nebraska passed 113-100. Believing he had sacrificed his career over Kansas-Nebraska, Richardson chose not to run again. His party's convention, however, nominated him on the first ballot. He expected to lose to friend Archibald Williams but won re-election by 579 votes. In 1856, he lost his race for Illinois governor to the new Republican Party ticket, which included John Wood for lieutenant governor. Ironically, Richardson in January 1858 would become the first governor of the Nebraska Territory. He returned to the war-torn U.S. Senate in 1863. He defeated his Quincy friend Orville Browning, who had been appointed when Douglas died in June 1861.

Reg Ankrom is a member of the Historical Society and a local historian. He is a member of several history-related organizations, the author of a history of Stephen A. Douglas, and a frequent speaker on pre-Civil War history.

Sources

Reg Ankrom, Stephen A. Douglas: The Political Apprenticeship, 1833-1843. Jefferson, NC: McFarland Publishing Co., 2015.

Maurice Baxter, Orville Hickman Browning: Lincoln's Friend and Critic. Bloomington: University of Indiana, 1957.

William H. Collins and Cicero F. Perry, Past and Present of the City of Quincy and Adams County, Illinois. Chicago: The S.J. Clarke Publishing Co, 1905.

Robert P. Howard, " ‘Old Dick' Richardson, the Other Senator from Quincy," Western Illinois Regional Studies. Vol. 7, Spring 1984.

Abraham Lincoln, "To Joshua Speed," Aug. 24, 1855. The Collected Works, 1858-1860. Roy Basler, ed. New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University Press, 1953.

Howard Jones, Abraham Lincoln and a New Birth of Freedom. Lincoln: University of Nebraska, 1999.

John M. Palmer, Ed. The Bench and Bar of Illinois: Historical Reminiscent. Chicago: The Lewis Publishing Co., 1899.

"Pre-Civil War Home Being Razed," Quincy Herald-Whig, May 15, 1962.

Dennis Thavenet, "William Alexander Richardson: 1811-1875." Doctoral thesis, University of Nebraska, 1967.

David Wilcox and Judge Lyman McCarl, Quincy and Adams County: History and Representative Men. Chicago: Lewis Publishing Co., 1919.