Vigilante action in Kingston ends in man's killing

Kingston is in Adams County’s southeast corner. The town was laid out in 1836 by Thomas King and eventually grew into a bustling relay station on the main stagecoach route between Quincy and Meredosia.

The town of 200 had stores, hotels, saloons, blacksmith shops and a doctor. Most businesses were established to provide for the needs of the traveler on his way to Springfield.

Social life centered on the general store, two churches and the school, which was housed in the Masonic hall. All of these institutions were places for people to fraternize, making a close-knit village. Thirty miles east of Quincy, the town was without telephone, telegraph or a railroad. The stagecoach was the town’s only tie to the outer world.

On July 20, 1893, the Kingston stagecoach driver brought news to Quincy of the murder of Solomon Bradshaw by a mob of vigilantes. The night before, more than a dozen men called Bradshaw out of a house and fatally shot him.

The house was owned by a married couple named Breckenridge who were held in low regard by the community.

The husband was in jail because the month before he had threatened another man while attempting to extort money from him. Mrs. Breckenridge had lured the man, Daniel Kenney, into their house. Her husband was hiding under a bed, prepared to rob him with a gun.

Katie Breckenridge had a reputation of keeping

company with other men. She and her husband had been the talk of the town after the Kenney incident.

Bradshaw, a traveling salesman from Quincy, had been seen frequenting the Breckenridge house overnight multiple times. At the McVay and Nations general store, gossip among patrons resulted in a call for tar and feathers to abate the nuisance.

George Nations, store proprietor, had taken the lead in churning up village opposition to the Breckenridges’ activities. Nations talked 14 local men into blackening their arms and faces and confronting Breckenridge and her guest.

Nations gave George Kistner a .44-caliber revolver, telling him it had blank cartridges. The plan was for Nations to tap on the door. The crowd would then order them to stop

the immoral acts and persuade them to leave town.

The mob proceeded toward the Breckenridge house about 10:30 p.m. disguised in shoe polish and paper hats.

Bradshaw and Katie Breckenridge were in the front parlor when they heard the men approaching.

Solomon turned down the light and quickly shut the front door. At the same time, someone from the mob exclaimed “Rush up, boys,” followed by shots from the revolver.

The first bullet pierced Bradshaw’s heart, killing him instantly. The men then demanded entry, but Katie informed them that Bradshaw was dead and the mob quickly dispersed.

Katie sent for the local justice of the peace. He arrived within a few hours, and with the help of a justice from Barry, formed an

inquest jury. Katie was the only witness.

George Nations and two others from the mob were on the jury and had traces of black on their collars. The inquest found that Bradshaw had been shot by a mob but nobody saw the perpetrators. Katie’s testimony recognizing juror George Nations as part of the mob was ignored. This hastily completed report is what the stagecoach driver brought to Quincy the next afternoon.

City newspapers and the public clamored for more news of the crime. It took 48 hours for county officials to send a second inquest jury with sheriff’s deputies to find out what actually happened.

The six jurors spent 16 hours interviewing witnesses to find out who was involved in the murder. Dozens of residents were interviewed, but at the

end of the first day, no one would say who had participated in the mob or confirm who fired the shots. It would take several weeks of investigation to learn the truth.

A grand jury indictment of 14 men came two months after Bradshaw’s death. George Kistner was charged with firing the gun Nations gave him. Kistner, thinking the gun was loaded with blanks, had been convinced that the noise would scare the couple into leaving town.

He fired the gun at the first approach of the Breckenridge door, ending the mob’s action as quickly as it started.

The trial took place 16 months after Bradshaw’s murder. By the time the case went to court, investigators had determined that George Nations was the primary instigator in organizing the mob. He used his store to agitate the community.

He also gave Kistner the loaded gun, letting him think it was harmless. And Nations supplied the disguises to the mob.

Despite Nations’ activity, Kistner was held responsible for the death.

The jury could not consider

the fact that Kistner

thought the gun held blanks. Its instructions by the judge said that ignorance

was not to be used as

an excuse.

The prosecution still insisted that Nations and the other defendants had acted

illegally in confronting

the pair that night. Since the altercation resulted in murder, all were equally guilty of the crime.

Despite the above instructions, the jury found only George Kistner guilty of manslaughter. Nations and the others were acquitted of all charges.

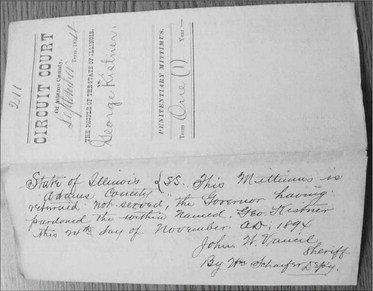

As a result of the verdict, the newspapers proclaimed Kistner the scapegoat in the case. At Kistner’s sentencing, Judge Orr gave him one year in the penitentiary.

After pronouncing the sentence, the judge apologized to Kistner, telling him he would pardon him if he could, and that it was a matter of profound regret that the jury could not acquit him.

After pronouncing the sentence, Orr concluded that executive clemency would soon pardon Kistner, correcting what the jury could not do.

A petition was immediately circulated asking Gov. Peter Altgeld to pardon Kistner. Within a week, the petition had 1,000 names that included most of the jury that convicted him. The governor acted quickly, and Kistner was released after serving less than month. The Quincy newspapers all mourned the lack of justice for Bradshaw.

Dave Dulaney is a local historian and a member of several historyrelated organizations. He is a speaker, author and a collector of memorabilia pertaining to local history and steamboats.