Failure of Tillson Combine bankrupts Second State Bank

By the early 19th century, businessmen of most towns along the Mississippi River had conceded commercial control of the river to St. Louis. Almost every company that tried to challenge St. Louis's position in the growing river economy failed.

One that failed -- spectacularly so -- was a partnership involving John Tillson Sr. of Quincy, which sought to shift the hub of upper Mississippi River trade from St. Louis to the Illinois side at Alton. The results were disastrous. When the Tillson Combine went under, it took with it the second State Bank of Illinois.

As one of the frontier's oldest settlements, St. Louis was the primary port for shipments of commodities like pork, beef, wheat, and flour, and it was a center for trade in consumer goods from the East. Most merchants from towns along and inland of the Mississippi went to St. Louis to buy merchandise to sell and trade in their stores.

Quincy was able to develop its own power as a shipping point because it was far enough upriver from St. Louis to avoid direct competition. Quincy's geography alone gave it several competitive advantages over other river towns in the region. For example, the Illinois River level usually fell earlier than the Mississippi's in the summer, reducing commodity prices Illinois River markets paid. Instead of selling at Beardstown, Meredosia, or Naples, farmers found they could afford to haul their commodities to Quincy and Alton, where the river remained navigable and where higher prices for their commodities more than offset the cost of transportation.

St. Louis cemented its dominance over the upper Mississippi River with the opening of the lead trade in Galena in 1826. George Collier, a 30-year-old St. Louis merchant, began sending St. Louis-based river boats for lead mined in northwestern Illinois. Collier's company shipped the lead through a New Orleans broker to eastern factories, where demand for the metal was white hot. He increased his profits and locked them in by loading his Galena-bound boats with freight and then eliminated competition by discounting the freight's shipping costs to mine owners there. As the squeeze in profits forced other boats off the river, Collier raised rates to his own customers, who had nowhere else to go.

The Alton combine with which Tillson allied himself had two objectives in mind. The first was to see that a proposal to create a second state bank, whose capital they would access to finance the Alton project, won approval in the Illinois Legislature. The achievement of that objective would facilitate the second: to make Alton the commercial hub of the upper Mississippi.

Along with Tillson, the Alton group included former New England sea captain Benjamin Godfrey and Winthrop S. Gilman of Alton, Thomas Mather of Kaskaskia, Judge Theophilus Smith of Edwardsville and Samuel Wiggins of Cincinnati.

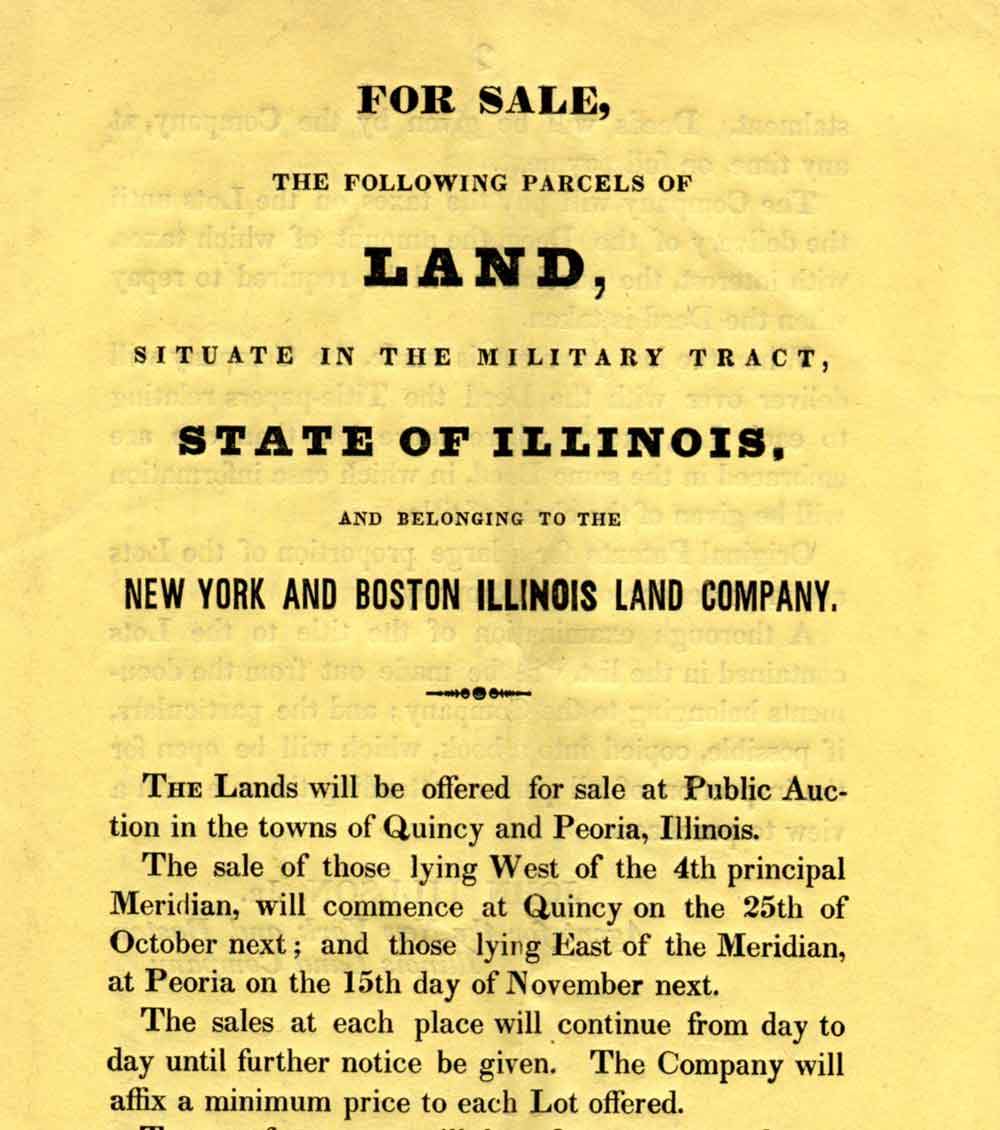

A wealthy land speculator, the Massachusetts-born Tillson moved his "New York and Boston Illinois Land Company" from Hillsboro to Quincy in 1837. His successful speculations made him the second largest landholder in Illinois with ownership of 424, 160 acres. His Quincy House hotel, completed in 1838 at a cost of $106,000 on the southeast corner of Fourth and Maine, was considered the finest hotel in the West.

Godfrey and Gilman were partners in Alton's largest freight-forwarding firm, Godfrey, Gilman & Company. They hatched the plan to challenge St. Louis for pre-eminence on the river.

Godfrey, for whom the southwestern Illinois city is named, was a wealthy businessman and philanthropist. An expertise in land, lead, smelters, and ships advanced his desire to add to his fortune by making Alton a riverside empire to rival St. Louis. As the father of eight girls, he established the Monticello Female Academy, today's Lewis and Clark College.

Gilman was the son of a wealthy New England land and banking family. An abolitionist, it was he who had allowed the Rev. Elijah P. Lovejoy to store his printing press in a Godfrey, Gilman warehouse in Alton. Lovejoy was killed at the warehouse on Nov. 7, 1837, while trying to prevent a pro-slavery mob from destroying the press.

Mather had been a Democratic state senator who, remembering the losses and failure of the first state bank, strongly opposed establishing a second one. His opposition vaporized when the Alton group offered to make him the bank's president if he would support it.

Smith was the sole Democratic justice on the four-member Illinois Supreme Court when he joined the Alton enterprise. He quit and became an opponent when its methods became clear to him.

Wiggins had been a perennial player in Illinois politics and finance. In 1831, he personally bailed out the state when the first state bank could not meet its obligation to redeem its heavily discounted notes at face value. Legislators had ignored a duty to levy taxes to pay the notes. With no clear way to pay for them, they authorized the state to borrow $100,000 from Wiggins. The estimated cost to Illinois taxpayers ended up being $400,000 -- and a ready issue in political campaigns for years to come.

Stock in the second Illinois bank was quickly subscribed (a subscription is an agreement to buy a given number of shares at a specified price at a later date), by New York and Connecticut investors arranged by the Alton group. These arrangements violated provisions of the bank's charter that the stock be subscribed by citizens of Illinois and that subscriptions be in small amounts to prevent large investors from controlling the bank. The Alton group hid the out-of-state subscriptions by sending agents throughout the state. They got unsuspecting Illinoisans to authorize Tillson and his Alton group partners to subscribe shares for them, transfer the shares, by which the group gained control. Few Illinoisans had any idea what they were signing.

Recalling the scheme, Gov. Thomas Ford of Quincy was amazed by its scope:

"Many thousands of such subscriptions were made in the names of as many thousands who never dreamed of being bankers, and who do not know to this day that they were ever, apparently, the owners of bank stock."

The scheme succeeded in giving the Alton group control of the bank, which began operating in 1835. They appointed Mather president and elected the majority of the bank's nine directors. Quincy lawyer Archibald Williams of Quincy, was elected a director and was successful in getting a branch of the bank established in Quincy.

The new state bank lent Godfrey, Gilman $800,000, which it used to buy heavily into Galena lead and which was shipped to Alton. Piling up the metal in Godfrey, Gilman warehouses, the goal was to corner the lead market. The plan achieved initial success as prices rose quickly from $2.75 to $4.25 per hundredweight. In little time, however, other forces began to intervene. As prices rose, eastern demand for lead fell off. Costs of operations forced the group to start selling lead, which increased the velocity of the downward spiral in its value. When the Alton combine's corner collapsed, Godfrey, Gilman collapsed with it. The state bank's losses were more than $1 million, two-thirds of its capital, which made it virtually insolvent in its first year of operation. Eventually, the bank failed. Illinoisans would not know that for two years.

Gov. Thomas Carlin of Quincy, elected in 1838 and angered by the bank's suspension of payments on notes, asked the legislature to investigate. After the discovery of numerous instances of malfeasance, Carlin recommended repeal of the bank's charter. The legislative investigation revealed that Wiggins had borrowed heavily from the bank and collateralized the loans with stock he had not paid for. Mather escaped accountability and went into railroading, buying the Northern Cross line between Meredosia and Springfield.

Judge Smith, who had studied law under Aaron Burr in New York, was the first of only two statewide officeholders to be impeached. He was exonerated.

Tillson, unscathed by the scandal, returned to his land company. While on business in Peoria, he died of apoplexy on May 11, 1853. He was 57.

Reg Ankrom is a member of the Historical Society of Quincy and Adams County, the author of a biography of Stephen A. Douglas of Quincy, and a frequent speaker on pre-Civil War history.

Sources

"Abraham Lincoln, Banking and the Panic of 1837." http://abrahamlincolnclassroom.org/abraham-lincoln-in-depth/abraham-lincoln-banking-

and-the-panic-of-1837-in-illinois

Reg Ankrom, "The Political Apprenticeship of Stephen A. Douglas: Illinois 1833-1843." Unpublished manuscript.

Edward F. Dunne, Illinois: The Heart of the Nation. Vo.l 1. Chicago: The Lewis Publishing Co., 1933.

Thomas Ford, History of Illinois from 1818 to 1847, edited by Milton Milo Quaife, Vol 1. (Chicago: The Lakeside Press, 1945.

Robert Howard, Illinois: A History of the Prairie State. Grand Rapids, Michigan: William B. Eerdman's Publishing Co., 1972.

Timothy R. Mahoney, River Towns in the Great West: The Structure of Provincial Urbanization in the American Midwest, 1820-1870. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1990.

Theodore Calvin Pease, The Frontier State, 181-1848. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1987.

Christiana Holmes Tillson, A Woman's Story of Pioneer Illinois. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 1995.

Gen. John Tillson, History of Quincy. Chicago: S.J. Clarke Publishing Co., 1905