Scotland's Stobie family had history of abolition

In 1834 the Stobie family left the seaside village of Aberdour in Scotland's kingdom of Fife for the United States. They traveled through New Orleans and up the Mississippi River to Quincy. James and Margaret Stobie had at least 12 children in Scotland, and most of them came to Quincy. It is unknown if Margaret Stobie made the voyage from Scotland, or died in her homeland. This Scottish family ultimately made meaningful contributions to the antislavery movement.

Upon arriving, it didn't take long for James to connect with Americans who challenged slavery. He was among the large cadre of Quincyans at the 1837 Illinois Antislavery Convention in Alton. James' business partner Samuel Winters also attended, and they attended one of Elijah Lovejoy's final lectures before his murder a week after the meeting. Several of James' children also got involved with Quincy's antislavery movement.

Alexander Stobie, the youngest son born in 1824, worked for John Van Doorn's Quincy lumber business. Van Doorn's riverfront sawmill was a well-used sanctuary and terminal for fugitive slaves fleeing to Canada. Alexander also worked alongside the Clark brothers of New Philadelphia and was a close neighbor of this free black family, all living at various homes on South Third Street. In the mid 1850s Keziah Clark and her children moved to Quincy from former slave Free Frank McWorter's town. Simeon Clark and Alexander Stobie were both sawyers for Van Doorn, laboring on the corner of Front and Delaware streets. Simeon was vocal about his secret Underground Railroad work after the Civil War ended. Alexander knew him for several years.

Alexander Stobie married Isabella Cooley in 1847 and they had at least one son, Charles, before she died. His second wife was Emeline Whipple, a widow and mother of two. She died in 1870 and is buried in Woodland Cemetery. After the Civil War he became partners with his former boss, John Van Doorn, and worked on Quincy Bay with Daniel C. Wood's ice business. Alexander was a witness for Daniel Wood's new ice hook improvement, and the 1875 patent details its purpose of tilting and handling heavy ice cakes with greater ease. The ice hooks are not known to have been produced.

Jane Stobie, the youngest daughter born in 1827, was a student at Mission Institute in the school's waning days. She graduated in 1850, six years after the institute's founder, David Nelson, died. The institute was a missionary training school but was well known for its antislavery principles. Nelson had been chased to Quincy by a pro-slavery mob, and the Stobie children attended the school soon after three other students were imprisoned for enticing slaves away from their Missouri owners.

Jane met fellow student William C. Shipman there and the two wed in 1853 in Waverly. William Cornelius Shipman grew up on a farm in newly settled Hadley Township in Pike County. William's father, Reuben Shipman, signed the New Philadelphia plat book in 1836. Jane's father-in-law was one of the earliest farmers in Hadley Township, and he certified a copy of the plat and survey of former slave and proprietor Free Frank McWorter's town.

After graduation and marriage, William and Jane Shipman left Quincy for Connecticut, where William attended New Haven Theological Seminary. He graduated in 1853, and the couple, appointed by the American Board of Foreign Missions, set sail on the ship Chaica from Boston as missionaries to the Sandwich Islands. Jane was pregnant with William on the voyage. The family settled at Lahaina, Maui. They had three children before her William died of typhoid in December 1861. Jane Stobie Shipman then moved to Hilo, Hawaii, where she opened a girl's boarding school. She married William Reed in 1868, and he helped raise Jane's children.

In the 1870s Jane sent her son William to Quincy to visit his Uncle Alexander. He recalled his time in Quincy, ice skating on the frozen river and reading "Pilgrims Progress," a gift from his uncle. Young William graduated from Knox College in Galesburg. He was homesick for Hawaii, and studied agriculture at Knox so he could return to the islands and help manage his stepfather's ranches. Reed died in 1880 and Jane inherited his land holdings. Jane's son William eventually bought an estate on Reed's island, and it is a popular tourist destination today known as the Shipman House Bed and Breakfast Inn.

Jane's brother Alexander retired to Hawaii soon after 1900 to be with her. Jane died in 1904, but Alexander Stobie lived until 1917. His son Charles Stobie moved with him to Hawaii and he used his many years of banking experience there. Charles' first banking job was at Lorenzo and Charles Bull's Bank in Quincy.

Catharine Stobie (born 1819) graduated from Mission Institute in 1846. She married the Rev. Samuel Jones in Illinois and they moved to the West Indies as missionaries in 1852. Catharine's original letters and testimonials from Quincy minister Elijah Griswold and philanthropic emancipationist Lewis Tappan are at the Amistad Research Library in New Orleans.

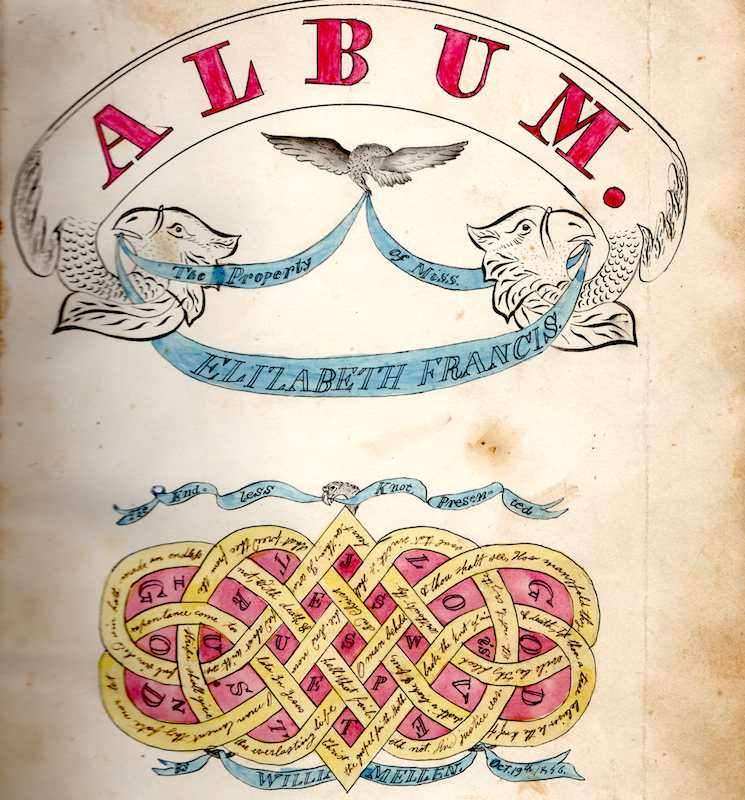

Janette Stobie (born 1821) also was a student at Mission Institute. She wed fellow student James Weller in 1850, and he was ordained in 1851 in Waverly. The pair became missionaries in Jamaica before Janette died in 1866. Miss Elizabeth Francis's Mission Institute yearbook album from 1846 preserves Janette's entry: "Listen to the cry of dying millions wafted upon every gale, come over and help us,… Will famishing multitudes cry in vain for the bread of eternal life, when such a rich provision is made for all?"

William Stobie (born 1813) also was associated with Mission Institute. A biography of Dr. David Nelson states that William was among a group that included John Van Doorn and Dr. Richard Eells, who purchased or rented institute property to build homes. He married Ann Francis in Adams County and they moved to St. Louis, where he became a flour miller.

Heather Bangert is involved with several local history projects. She is a member of Friends of the Log Cabins, has given tours at Woodland Cemetery and John Wood Mansion, and is an archaeological field/lab technician.

Sources

Cahill, Emmett. Shipmans of East Hawaii. Honolulu, HI: University of Hawaii Press, 1995.

Congregational Publishing Society. Congregational Year Book, 1894

Directory of American Tool and Machinery Patents, U.S. Patent 165, 778.

Francis, Elizabeth. Mission Institute Album. Collection of the Historical Society of Quincy and Adams County, 1846.

Quincy City Directories, 1848, 1855-1875

Quincy Daily Herald, 29 Feb. 1860: 4.

Richardson, William A. Jr. "Dr. David Nelson and His Times." Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society 13 (January, 1921): 433-453.

Walker, Juliet E.K. Free Frank: A Black Pioneer on the Antebellum Frontier. Lexington KY: University Press of Kentucky, 1982.

W. H. Shipman Limited. History.